David Campany

Writer and Curator of a Handful of Dust

London

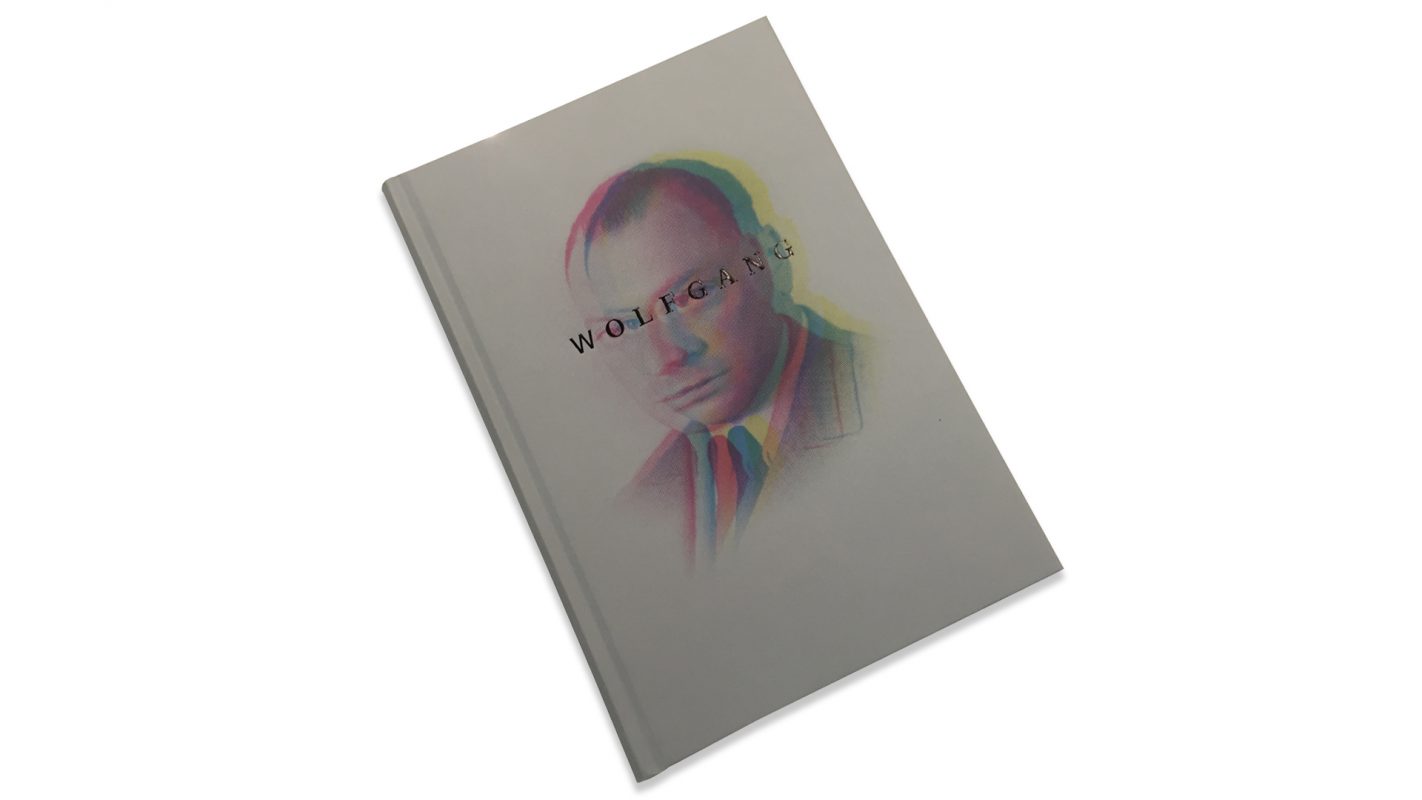

1000 Words Editor in Chief, Tim Clark speaks with the writer and curator David Campany ahead of his forthcoming exhibition a Handful of Dust, which opens at the Whitechapel Gallery on June 7th. Having previously been presented at Le Bal, Paris and Pratt Institute, New York, this parallel exhibition and book project sets out to track the passage or ‘biography’ of a photograph made in 1920 by Man Ray (Or was it Duchamp? Or perhaps Man Ray and Duchamp?) as its meaning shifts in emphasis from context to context; and to look at how those meanings might suggest associations with other unlikely images from the last century.

Their conversation shares views on how the meaning of the photographic image lies in its destination; the idea that we are living in a visual culture that may have trained us not to look, or expect to look, at any one image for very long; as well as the argument that reading about politics, philosophy, anthropology, history and psychoanalysis is perhaps more important for students than reading about photography.

Tim Clark: I can only assume the Dust Breeding image must have been orbiting your imagination for some time before putting together the proposal for the Le Bal show. Where and when did you first encounter the work and to what extent has your relationship to it changed over time?

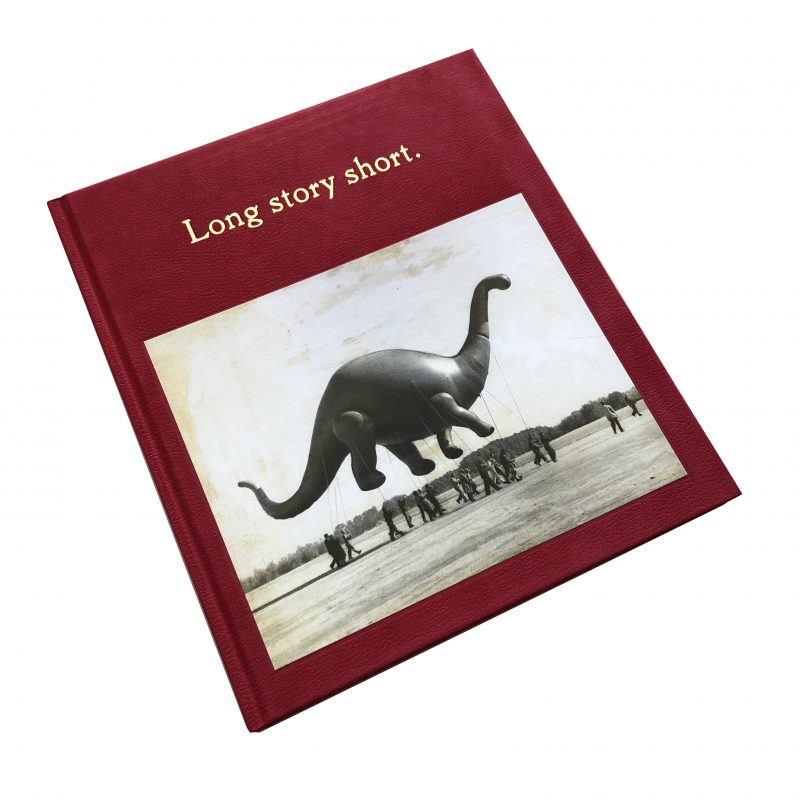

David Campany: It would have been 1989, when I was an undergrad student in London. It was the 150th anniversary of photography and the Royal Academy had its first ever show of photographs. So embarrassingly late! Anyway, in a section on modernism I saw this strange, almost abstract photograph from 1920. It was titled Dust Breeding and credited to Man Ray. A flat receding plane, without obvious scale, covered in a film of dust with clumps, and what looked like geometric lines. I remember feeling a little dismissive. It was ugly and it seemed pointless. But it stuck in my mind. A little later I came across it again, while reading about the artist Marcel Duchamp. Man Ray had photographed the dust gathering on a sheet of glass that would later become part of Duchamp’s great work The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1915-23). Duchamp wanted to keep parts of the dust by fixing it with varnish – a sort of visual way of trapping time. So it was an art photograph that took as its subject the dust of another artwork. That’s unusual. Sometimes this image is regarded as a work by Man Ray; sometimes it’s regarded as a document of an artwork by Marcel Duchamp.

Later I discovered that when it was first published it was titled A View from an Aeroplane, which really twists the possible meaning. This was shortly after the First World War, and aerial photography had become commonplace.

Much later still, I discovered the image had been important to many conceptual artists of the 1960s and 70s. Meanwhile the photo was cropping up in theoretical and philosophical texts about the nature of photography as trace or index. So my initial dislike turned to fascination.

TC: Thinking about how it’s been regarded and where the authorship might reside, how do you view Man Ray and Duchamp’s respective roles? Are we talking about a most unique form of collaboration?

DC: That photograph was in and out of various avant-garde journals and books for over four decades. Then in 1964 an edition of ten prints was made and both men signed them on the front. The respective roles of the image vary, depending on how the photo is used and where the emphasis falls. I guess in that sense it’s a photo that dramatises a tension that exists in all photographs, between art and document, intention and chance, fact and wish, between what’s in the photograph and what context the photograph is in. We’re interested in photography, and to that extent we’re somewhat invested in the idea of authorship. But maybe authorship isn’t the most significant thing about photography. It’s a medium haunted by the fact that only under very limited circumstances does the ‘author function’ (as Michel Foucault once called it) actually mean much. We see hundreds of photographs in our daily life and barely stop to think about the authorship of any of them. News photos, design photos, advertising imagery. I was looking at a book of teeth photos today, while waiting to see my dentist. No idea who took them, but no less fascinating for that.

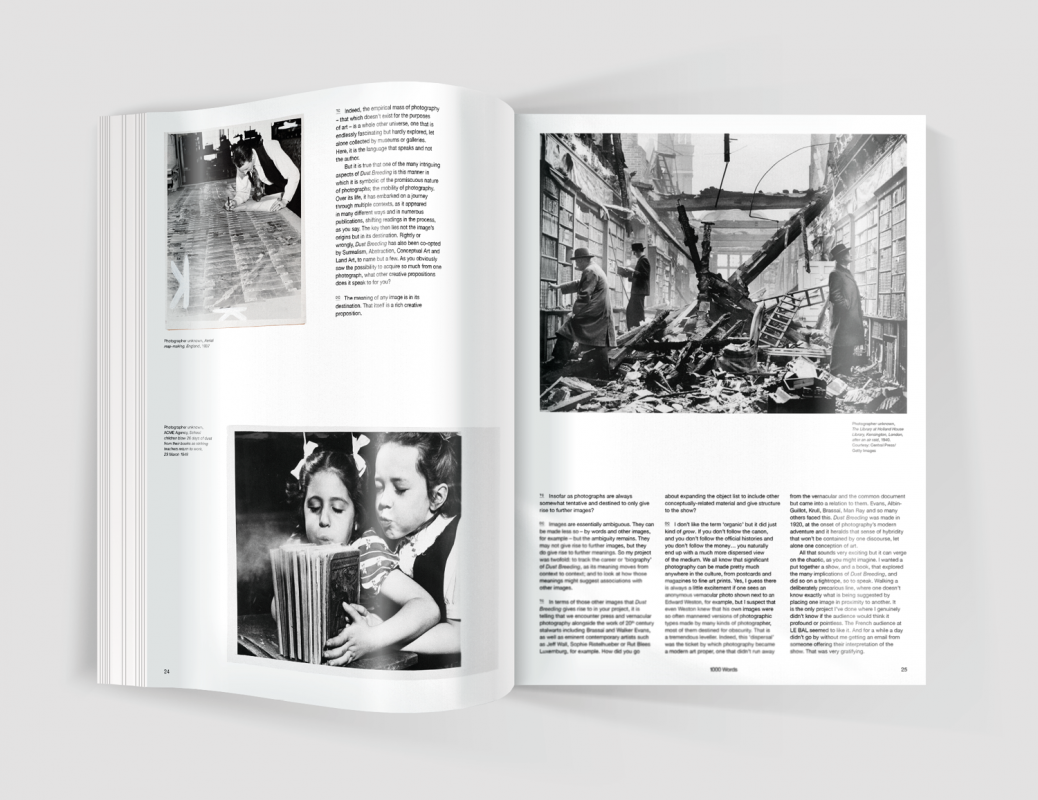

TC: Indeed, the empirical mass of photography – that which doesn’t exist for the purposes of art – is a whole other universe, one that is endlessly fascinating but hardly explored, let alone collected by museums or galleries. Here, it is the language that speaks and not the author.

But it’s true that one of the many intriguing aspects of Dust Breeding is this manner in which it is symbolic of the promiscuous nature of photographs – the mobility of photography. Over its life, it has embarked on a journey through multiple contexts, as it appeared in many different ways and in numerous publications, shifting readings in the process as you say. The key then lies not the image’s origins but in its destination. Rightly or wrongly, Dust Breeding has also been co-opted by Surrealism, Abstraction, Conceptual Art and Land Art, to name but a few as well. As you obviously saw the possibility to acquire so much from one photograph, what other creative propositions does it speak to for you?

DC: The meaning of any image is in its destination. That itself is a rich creative proposition.

TC: Insofar as photographs are always somewhat tentative and destined to only give rise to further images?

DC: Images are essentially ambiguous. They can be made less so – by words and other images, for example – but the ambiguity remains. They may not give rise to further images, but they do give rise to further meanings. So my project was twofold: to track the career or ‘biography’ of Dust Breeding, as its meaning moves from context to context; and to look at how those meanings might suggest associations with other images.

TC: In terms of those other images that Dust Breeding gives rise to in your project, it’s telling that we encounter press and vernacular photography alongside the work of 20th century stalwarts including Brassaï and Walker Evans, as well as eminent contemporary artists such as Jeff Wall, Sophie Ristelhueber or Rut Blees Luxemburg, for example. How did you go about expanding the object list to include other conceptually-related material and give structure to the show?

DC: I don’t like the term ‘organic’ but it did just kind of grow. If you don’t follow the canon, and you don’t follow the official histories and you don’t follow the money… you naturally end up with a much more dispersed view of the medium. We all know that significant photography can be made pretty much anywhere in the culture, from postcards and magazines to fine art prints. Yes, I guess there’s always a little excitement if one sees an anonymous vernacular photo shown next to an Edward Weston, for example, but I suspect that even Weston knew that his own images were so often mannered versions of photographic types made by many kinds of photographer, most of them destined for obscurity. That’s a tremendous leveller. Indeed, this ‘dispersal’ was the ticket by which photography became a modern art proper, one that didn’t run away from the vernacular and the common document but came into a relation to them. Evans, Albin-Guillot, Krull, Brassaï, Man Ray and so many others faced this. Dust Breeding was made in 1920, at the onset of photography’s modern adventure and it heralds that sense of hybridity that won’t be contained by one discourse, let alone one conception of art.

Well, all that sounds very exciting but it can verge on the chaotic, as you might imagine. I wanted a put together a show, and a book, that explored the many implications of Dust Breeding, and did so on a tight-rope, so to speak. Walking a deliberately precarious line, where one doesn’t know exactly what is being suggested by placing one image in proximity to another. It’s the only project I’ve done where I genuinely didn’t know if the audience would think it profound or pointless. The French audience at Le Bal seemed to like it. And for a while a day didn’t go by without me getting an email from someone offering their interpretation of the show. That was very gratifying. I’m curious to see what London makes of it.

TC: Dust Breeding is such a wonderful title. What do you interpret to be its significance? Given the socio-historical context, is this an allusion to post World War 1 trauma and anxiety? Or are we dealing with religious connotations, namely in the Christian lexicon (eg. ashes to ashes, dust to dust)? Or perhaps we are witnessing a channelling of the complex sexuality of Duchamp’s art? After all, he said that everyone understands eroticism, but no one talks about it, and that through eroticism one can approach important issues that usually remain hidden.

DC: All of the above! The title is thought to come from a sign Duchamp hung in his studio: Do not touch: Dust Breeding. As if his studio was a farm, or a laboratory. Dust, that inevitable intrusion is being harnessed, willed into existence and form. Duchamp spoke of devising various procedures to ‘can chance’. To trap it, preserve it. Allowing dust to gather, as a trace of time is a sort of canning of chance. Photography too can be a way of canning chance. The dust photograph is thus a trace of a trace.

The subtitle of my book is From the Cosmic to the Domestic. Dust unites those realms.

TC: And what about the book/exhibition’s title, a Handful of Dust. It’s a line taken from T.S Eliot’s poem, The Waste Land published in The Criterion in 1922 – the same year the dust image first graced the pages of Littérature, is it not? Do you see one as an analogy for the other?

DC: Not just the same year, it was the very same month. October 1922. Eliot’s great poem is modern in the same way as the dust photograph – a hybrid work of allusion and association that pictures the world in fragments if not ruin, but sees the world’s possible redemption in those fragments too. It’s a coincidence I couldn’t ignore.

TC: Dust is obviously the enemy of photography yet as a subject of a photograph it also represents something entropic, an affirmation of the real in all its imperfections and dirt, which in a way is the opposite of modernity and progress. It represents everything ‘out there’ in the universe but also all that is below our feet.

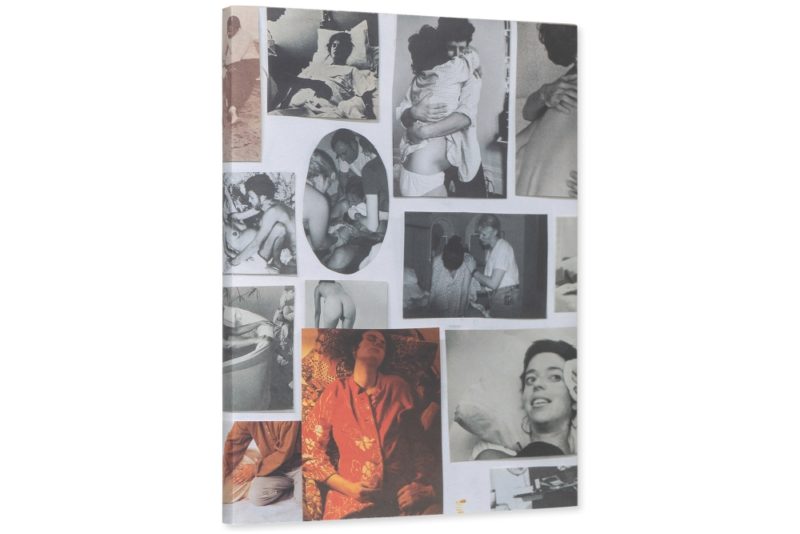

Could you talk a bit about the process of editing the accompanying book that has been published by MACK. What was your idea to best express the images and their associations in this format and how did it differ from the exhibition experience?

DC: The format of the book is unusual. It’s a sequence of about 160 images, uncaptioned. It’s roughly chronological, with a few deliberate leaps across history. In the middle of the sequence sits a separately bound long essay. So you’re free to cast aside the writing and give yourself up to the task, or pleasure, or pleasurable task of navigating images that are tethered tentatively to each other. That’s as close as I’ve come in book form to the experience of the gallery setting, which of course isn’t very close at all, since books and shows are very different experiences (for all the obvious reasons). It’s true that some shows, notably thematic shows, can end up being “books transferred to the wall”. Naturally I was keen to avoid that. All I’d say is that the two photo-related activities that make me happiest are the working out of multivalent sequences on the page and the working out of relations between images in a physical space. A book needs to be a good book, and an exhibition needs to be a good exhibition. With this project the material works well in both settings. I worked on both simultaneously.

TC: The fact that the images are uncaptioned is interesting since earlier in our discussion we touched upon how text can either compliment or contradict an image’s meaning, albeit with ambiguity intact. Do you see the way you have sequenced and arranged the images for the book as a kind of writing in itself anyway? Is it a way not so much to write about photography but with it?

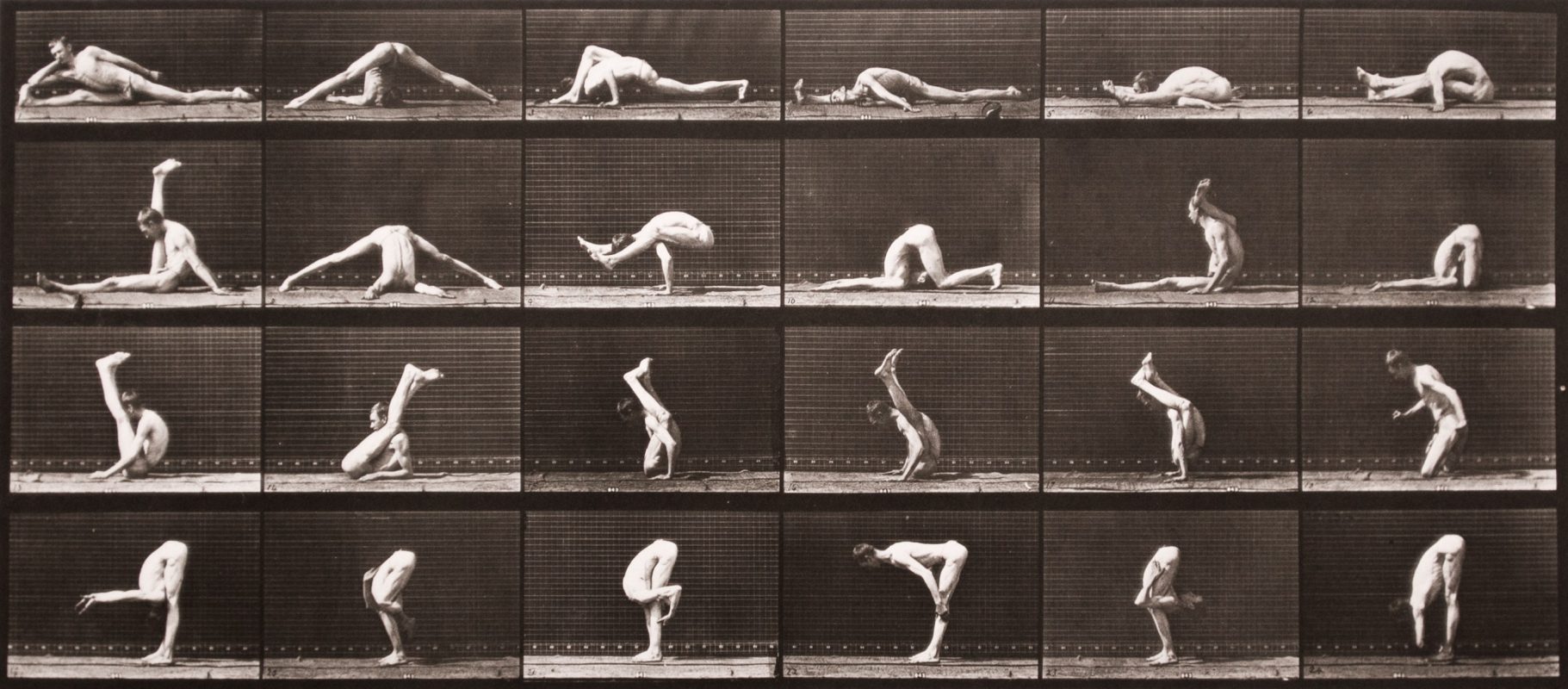

DC: Well, I was at pains earlier to say that images can be shaped by other images as well as text! Is a sequence of photographs a form of literature? Maybe, and I suspect that in the past I’ve talked about it in that way. But I think we use analogies with literature because we don’t have an adequate vocabulary for describing what happens when our response to one photograph is informed by another and another. We just don’t. I’m always surprised by that. Back in the 1920s, when editing was really coming into its own, both on the page and in the cinema, there were filmmakers and film theorists developing really complex ways of talking about cinematic montage. Kuleshov, Eisenstein, Vertov. Revolutionary figures. But beyond a few texts on photomontage and collage there was no equivalent body of knowledge being assembled for photographic editing. This doesn’t mean photo editing wasn’t as advanced. In many ways it was, but we’re left with quite an impoverished way of talking about it. That’s not necessarily a disadvantage. Part of me finds it very freeing.

TC: Freeing? In what sense?

DC: I think it was Koestler who said that true creativity begins where language ends. That can be a very regressive idea, and has been used to defend all manner of clichés about artistic life. Nevertheless there are times when it can be freeing to not be able to give a name to what you’re doing.

TC: I think photography is all editing. We can never emphasis enough the pervasive and persuasive role of editing in determining meaning, via interstices between images, via movement between one photograph and the next, via the itinerary of the eye.

Speaking of which… Slowness and sustained looking versus quick, casual consumption of images is also something that I’m curious to hear your thoughts about. I’m recalling a passage from Victor Burgin’s essay Photography, Phantasy, Function (1980) that of course you know very well:

‘To look at a photograph beyond a certain period of time is to be frustrated: the images, which on first looking gave pleasure by degrees becomes a veil which we now desire to see. To remain too long with a single photograph is to lose the imaginary command of the look, to relinquish it to the absent other to whom it belongs by right: the camera. The image now no longer receives our look, reassuring us of our founding centrality, it rather, as it were, avoids our gaze. In photography one image does not succeed another in the manner of cinema. As alienations intrudes into our captation by the still image, we can only regain the imaginary, and reinvest our looking with authority, by averting our gaze, redirecting it to another image elsewhere. It is therefore not an arbitrary fact that photographs are deployed so that, almost invariably, another photograph is already in position to receive the displaced look.’

If you indulge me and imagine we ignore the date for a moment, Burgin could almost be describing our contemporary condition of waning attention spans, of photography in the age of distraction – an age in which the sheer volume of images we digest on a daily basis not just on the Internet but in the world around us is staggering. An age in which anybody with a smart phone is now a photographer but few have a sophisticated understanding of the uses and abuses of photography. At the moment of his writing, though, what do you think was his most pressing concern, given that psychoanalytic theories of photography such as the gaze, the imaginary and captation were only recently introduced? What precise aspects of visual culture was he writing in response to?

DC: You’d have to ask him that. That passage is fascinating for different reasons. Burgin’s argument is ontological, in that he feels there’s something built into the medium that makes photographs compelling to look at but only for a short while (“therefore”, as he put it, there’s always another image in place to take the displaced look). Against that ontological view we might say that we live in a visual culture that has trained us not to look, or expect to look, at any one image for very long… but we could. I’ve never quite made my mind up about that, and I guess there’ll never be a ‘court of appeal’ in which we have to make up our minds. But it is a question I think about, and it was on my mind a lot in this project, spiralling back to that one very singular image. Maybe images are like relationships. Some warrant a one-night stand, others demand a long-term commitment. And some you don’t see very often but they’re important to you nonetheless.

I was just reading a very suggestive essay by Hito Steyerl, titled Cut!, in which she suggests that each epoch of modernity has its own ways of editing (she’s concerned with movies but it applies to still photography too). The rhythms, the interstices change over time under different pressures. I think the Internet is generating a whole new set of rhythms and interstices on many fronts: in the online orchestration of images, in the online consumption of images, in the possibilities of retrieval and reconfiguration. I think you can see this in the number of books by photographers that have associative, elliptical edits. Such books seem to be influenced by, yet resistant to, online experience.

TC: This idea that we live in a visual culture that has trained us not to look is very interesting if not a little disconcerting. I guess I was not only thinking about the surfeit of imagery (via the Internet, billboard advertising, television, news photography etc.) that might avert our gaze but also about certain, self-conscious strategies present in art photography – namely typology and, more specifically, seriality as a means of creating the ‘displaced look’.

Someone whose work, given its nature, actively resists the idea of expecting viewers not to look at any one image too long is Jeff Wall, to name but one example. He doesn’t present groups or series of images as way of imagining photography, a practice of photography, he has described, as ‘so established it is almost unnoticed’. He has said, and as you included in your article for Source magazine, Quotations for an Essay about Editing (2009): ‘I notice it because I really cannot do it that way. I want each picture to stand on its own, with no sequential or thematic relationship to any other. At least, not any specific or organised relationship.’

What made you write about Jeff Wall’s Picture For Women (1979), a book again centred on one singular image, for which you received the International Center of Photography Infinity Award for Writing in 2012? Was this image initially a one-night stand that surprisingly developed into a long-term relationship?

DC: Published books are strange things. They seem to say: “This was all very intentional. It was written by someone who knew what they wanted to do, and they did it.” But nearly all my books have come about by chance, and never turn out the way they start. The one on the Jeff Wall image had a strange genesis. When Wall had a big retrospective at Tate Modern, in 2005, there was a day-long symposium where a bunch of people were each invited to choose and talk about just one of his photographs. Steve Edwards, Briony Fer, Michael Fried, Michael Newman, and others. I chose Woman with a Covered Tray, a very understated image that I loved, and still do. Then the organisers called me to say that nobody had chosen a work from the 1970s or 80s, and could I reconsider? I’d recently published a survey book for Phaidon, Art and Photography, in which I included Wall’s Picture for Women. That photograph had already attracted a lot of discussion but I doubted one thing that almost every critic seemed to assume, that the photograph was shot facing a mirror. We’re always making presumptions when we look at photographs. That fascinates me. Anyway, I gave my talk at Tate, and a few years later the artist Mark Lewis, who instigated the One Work series of books for Afterall/MIT asked if I’d push my thinking and turn it into a whole book on Picture for Women. There was more than enough to discuss, not just about that image but why so few art photographers set out to make singular photographs, belonging to no set, suite, series, typology, archive or other ‘body of work’. Making just one, to stand alone, is still very rare.

Intellectually, I’m rather allergic to books about ‘photography in general’. There’s so little you can meaningfully say about it in general. When I was an undergraduate I spent an afternoon talking with Susan Sontag (a long story) and she and I ended up discussing this issue. I was a great admirer of her essays but never liked her book On Photography. When she asked if I’d read it I was brave enough to tell her this. I didn’t like the sweeping tone, and the absence of reproductions in the book gave her an unearned license to sail over an entire field making sweeping generalisations. She said that was certainly a weakness of the book, and that at the time she’d found it difficult to talk about specific images. Many writers on photography do find that difficult – they relate to photography as a technical/social phenomenon. I was struck by her honesty. Then she said, very genuinely, that maybe one day I might write a book titled On Photographs, or even On a Photograph. I never forgot that conversation.

TC: That’s a great story and On a Photograph would be a fabulous title. You’ve referred to Wall’s Picture for Women before as ‘perverse’. Could you elaborate on that?

DC: It doesn’t picture any thing perverse, but it does picture perversely.

TC: Perverse, in terms of confounding us as viewers through the deliberately disorientating sense that we are looking through the reflection of a mirror? Perverse in terms of presenting us with several spectacles going on at once – like in Édouard Manet’s painting Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère, on which Wall modelled Picture for Women? I imagine these are just some of the work’s many obstinacies in giving up its meaning readily that intrigued you?

DC: Yes. It took me a whole book to explore the obstinacies and I still came to few conclusions. In general I find photographs ‘modelled’ on paintings insufferable. We can all think of endless corny and over-lit photographic remakes of Vermeer, Hopper, Chardin and so on. But Wall’s Picture for Women does address itself to the specific differences between the mediums. Manet’s painting really cannot be recreated photographically. It’s a painting. And Wall’s photograph is a photograph. That’s not a call for purity – all the mediums are free to mix and explore each other – but there’s a kind of dialogue that also clarifies differences.

TC: Yes, endless. When confronted with examples of photographers pursuing this line or gallerists and publishers embracing such practice, I immediately think to myself, ‘What a shame! What a shame that they still consider photography’s status as an art form to be a bit suspect.’ I think, ‘Are we really going to have this conversation again about the relationship between photography and painting?’ The same points seem to be rehearsed over and over again and comparisons are often facile. Yet, in the case of Wall’s Picture for Women I think it is clear we are dealing with something much more complex and sophisticated. Wall’s motives seem far from faithfully mimicking its source in photographic form but rather he deploys a large-scale tableau in order to force a reflection on spectatorship, to thrust us into a kind of cinematic space, to play with perspective, to muse on the ‘male gaze’ etc. Ultimately, this is done without lapsing into corny imitation – far from it.

However, if the picture plane is invisible in a photograph, how has Wall managed to make it visible? How do we ‘know’ whether this is a camera photographing itself in a mirror or one camera photographing another? What do you think Wall is trying to do, trying to break away from?

DC: I never think about what an artist might be “trying to do”. I’m more interested in what I am doing when I’m looking and thinking. The image provides the occasion for interpretation. It’s what John Cage called ‘response-ability’. I’m post-structural enough to know that meaning lies in its destination, not its origin. Maybe this is why I’m just as attracted to images by unknown photographers, and to the fields of photography where the author function plays little part. Film stills, snapshots, instrumental photos like press or police pictures.

Every few years I reread several of Roland Barthes’ books – his ‘autobiography’… S/Z… The Pleasure of the Text… Camera Lucida… and the anthologies of essays. His circling around the relation between authorship and his own response is constantly fascinating. It’s curious how Camera Lucida is so beloved by photographers, when that book is certainly not beloved of them. For Barthes, the photographer’s authorship and intention are the obstacles that come between the image and his response. Yesterday I was with William Klein, whose images Barthes discusses, but only to say they are rich in socio-historical detail. He has no time for Klein’s powers of observation or quick-witted timing, or compositional brilliance. All Barthes sees are clothes and faces. Taking my copy of the book from my bag I asked Klein what he thought of Barthes’ approach, all these years later. He grabbed the book in mock anger and wrote on the image, “That was me – William Klein”! I guess authorship is always going to be a complicated issue for photographers.

Jeff Wall is certainly a ‘name’ in contemporary art photography and his manner of image construction means that many audiences and commentators feel that when they’re looking at his work they’re somehow in his artistic head. I don’t feel that at all. I don’t feel he has a ‘point of view’, certainly not an emphatic one that crowds me out. He simply offers me very rich occasions for response.

TC: Are you at liberty to say what you are working on with William Klein?

DC: Klein is a giant of documentary photography, fashion photography, and filmmaking in the 20th century (he’s also a brilliant writer and designer, who took care of every aspect of his landmark photographic books). He’s American but moved to Paris in 1948 and went back only intermittently. As a result he’s not had a retrospective in the US, and there’s no single book with an overview of his whole career. We’re looking into the possibilities of both.

TC: Sounds fascinating and a long time coming. Which great British photographers do you feel have been drastically overlooked by our photographic institutions here in the UK? Who hasn’t received their dues?

DC: There are so many! Hannah Collins, Victor Burgin, Chris Killip and Nick Waplington are four very different practitioners, who exhibit and publish all across Europe and America but deserve attention from major British institutions. From a slightly younger generation – Hannah Starkey and Esther Teichmann spring to mind. From the past – I’d like to see a comprehensive show of the work of Edith Tudor Hart. Britain has a habit of not quite valuing its photographers, while the contemporary art scene in the UK still has a problem with the medium. It used to exasperate me. But now I just get on with doing what I can, prodding here and there, championing when the occasion arises.

TC: Indeed! And all those you listed certainly merit major shows here in the UK. Even though we are in the photographic backwaters, I find it hard to believe that they haven’t been approached at certain points in their respective careers.

Obviously you’ve curated and organised many exhibitions on an independent basis – from a Handful of Dust at Le Bal (2015), as we’ve discussed, to Mark Neville: Deeds Not Words at The Photographers’ Gallery (2013) or Walker Evans: The Magazine Work, which started at MOCAK in Krakow (2014). Would you ever consider taking a permanent post in a public gallery or museum?

DC: It would depend on the institution. I’ve seen really dynamic curators swallowed by the bureaucracy and hampered by the slow pace of museums. That’s cause for concern. I kind of fell into curating, having never set out to do it. And to be honest I fall into most things, usually by being invited. It’s all very haphazard. I have my interests and somehow they find outlets. I was listening to a wonderful radio interview with the actor Tilda Swinton. “So Tilda,” said the host, “you’re enjoying a remarkable career…” Tilda interjected: “I’m not having ‘a career’: I’m having a life.” A life photographic, that’ll do me.

TC: ‘A life photographic’ – that’s a very nice way to put it. However, I find the term ‘photographic’ a curious, slippery one when used to describe an individual work or form of art ‘practice’ (another odd word). In your mind, how is something ‘photographic’ as opposed to just plain photography?

DC: I agree. I wouldn’t use the term to describe an individual work or form of art practice. I’ve ended up with a working life that moves between writing, curating, making images, editing, teaching, broadcasting, public speaking, and so on, but nearly always to do with photography in one way or another. A life that could be reasonably described as photographic.

How is a specific work or practice photographic without being photography? Interesting question. Perhaps when it partakes of an element of what makes up photography. For example, we might say photograms are photographic without being photography. Suntans are photographic without being photography. Signalling a Morse code message with a flashlight is photographic without being photography. I think the term ‘photographic’ has come about to designate a whole range of important partial practices.

TC: Just going back to the various photographic elements that make up your working life… Do you consider writing to be at its core? And I’m curious: who do you write for? Do you ever have a specific reader in mind?

DC: The image is at the core. That’s what I orbit around, in different ways. I had no intention of writing, and didn’t take it seriously until I was around 30. When I started to write – which was by invitation, on the basis of a couple of public talks I’d given about my own photography – I thought I should impress my academic peers. But once I’d done that, it wasn’t very rewarding. It felt needy and paranoid.

As a kid, I think I was smart, but not academically smart. That meant I had a lot of intellectual and creative energy that was going to waste, which can be an awful feeling. For whatever reason, photography caught me just in time, in my latter teens. It gave me a doorway to so many things. So in the back of my mind when I’m writing, I see me at the age of 19. I’m trying to catch him, scoop him up, offer him something to reach for. I’m not trying to tell him it will all be fine, but I am trying to tell him that the struggle to look and think can be worth it, even when it leads to more struggle. I think this approach chimes with something that’s dying these days, especially in academia, and that’s the drive for clarity of expression. My first drafts of my writing are over-wordy and contorted. Most of my efforts go into the re-writing. I’m trying to say things as simply as I can. That doesn’t mean I’m trying to simplify, or ‘dumb down’. I’m looking for the clearest way of expressing even the most complex ideas. They’ll still be complex, but I want to give myself and my reader (who is really my younger self) the best chance of grasping them. This isn’t a programme for all writers, but it is the one that interests me.

TC: I’m now imagining your writing as a sort of indirect letter to a 19 year old you. Are there any rules for writing that you either follow in the present or which you would set your younger self in retrospect?

DC: The points made by George Orwell in his essay Politics and the English Language are valuable. Never use a phrase you’ve heard before. Think three times before you ever use an adjective (it always says more about you than about what you’re throwing it towards). Avoid euphemism and cliché (i.e., use language and try not to let it use you). Be suspicious of ‘popular wisdom’ and the consensual categories to which the mass media will default.

I recently listened to a lecture podcast by Susan Sontag, and before she got to her main subject she said this:

“My work is much more intelligent than I am, and for a very good reason. Everything I write goes through many, many drafts. I feel that I am my first draft but then I’m a very good rewriter. I’m extremely tenacious, extremely stubborn. And I know how to improve, radically improve, what I get first onto the page. But I’m actually not as smart as the end result.”

That’s valuable. Kurt Vonnegut also has some good things to say about writing. Adorno on the essay form is terrific. Lastly, I find it worth listening carefully to great public speakers (and I don’t read their speeches). Speakers who can present, discuss, expound and think on their feet without notes, without hesitation, deviation, repetition or ‘TED talk’ over-rehearsal are very, very rare. Writing is, for me, connected to speech. Again, that’s not for everyone but it’s how I go about things. It might be because I found myself with a lecturing job before I found myself writing.

TC: Yes. And, of course, it was Orwell who commented on turning to long words and exhausted idioms as ‘like a cuttlefish squirting out ink’. Martin Amis has written some good thoughts too about writing as a war against clichés, how overused or abused words can become ‘dead freight’. What cliché is, he has said, is ‘heard thinking and heard feeling’. Sontag’s admission is interesting too. I was recently listening to an interview with Zadie Smith in which she said writing offers you a person in their best form – that ‘a book is somebody’s best self’, which rings very true.

I would like to ask: who has been the most remarkable writer on photography for you, personally? Who has been fundamental to your thinking on the medium?

DC: That Zadie Smith remark is interesting. When my students ask me who they should be writing for, I say: “Your future self. Write the best gift you could give your future self.” There isn’t a particular writer for me, no single figure who has been fundamental. As a reader, my most pleasurable moments come when the ideas and phrases from one writer overlap with another, when I move from book to book, or essay to essay. Those transitions – when one feels the presence of two minds and one’s own in the middle – can be so delicate, so energising, so joyously destabilising (a feeling Barthes once called ‘jouissance’). Putting down Fox Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature and picking up André Bazin’s essay on the photographic image. Reading Pierre Mac Orlan on Atget and then Molly Nesbitt on Atget. Reading Walter Benjamin and then Rosalind Krauss. Reading an interview with Roy deCarava, then reading Teju Cole on deCarava. Most recently it was putting down Siegfried Kracauer’s 1930s writings on the mass media and picking up Hito Steyerl’s The Wretched of the Screen. I guess that’s the editor in me, looking for the connections and the tensions.

TC: What makes a writer, David?

DC: I don’t know. The question feels too general. Perhaps a Writer (capital W) is a person whose words you want to reread. I read a lot of books and essays for information, and a lot for their intellectual ideas. But I tend to keep only the books I feel I shall want reread.

TC: Do you ever experience fear of writing? And are you a writer with any certain rituals?

DC: I’m one of those for whom writing is the way of testing not just what one thinks, but how one thinks, so there’s always a degree of fear involved. I have no rituals, although I do tend to follow Walter Benjamin’s advice, and try to write the end of a text in a location that’s different from where the rest was written. And wherever possible I’ll structure an essay or book visually, first sequencing the images that will become the spine of the writing.

TC: Are there any forms of writing on photography that you find unhelpful or repellent?

DC: I’m not fond of writing that presumes to speak for the reader or viewer; and there are many great thinkers that I find hard to appreciate as writers, but I wade through their texts anyway. I mention no names.

I do appreciate your reference to form. I feel good writing should be pursued in any mode, from the monographic essay and exhibition text, to the peer-reviewed academic essay, the interview, or the review. Academic writing is in a bad way at present, which is a shame. The whole peer-review process is limiting experimentation, and I see too many young academics feeling they need to conform to certain conventions for the sake of their career progression. It’s all become very risk-averse. I write for the academic journals only occasionally (who would want to live in a peer-reviewed culture? Sounds vaguely Stalinist to me).

In re-reading much of Roland Barthes’ work I’m struck by the radically experimental attitude he took to form: never presuming but always forging forms that were appropriate to his thought. Barthes could make even a list of his preferences zing with intellectual energy and startling honesty. It’s chilling to think he wouldn’t last a day in the present academic climate.

TC: It’s interesting that you mention Barthes’ list-making ability since I’m particularly fond of his J’aime, je n’aime pas (I like, I don’t like), amongst other works. I quote a few extracts from both directions:

‘I like: salad, cinnamon, cheese, pimento, marzipan, the smell of new-cut hay (why doesn’t someone with a “nose” make such a perfume), roses, peonies, lavender, champagne, loosely held political convictions, Glenn Gould, too-cold beer, flat pillows, toast, Havana cigars, Handel, slow walks…’

‘I don’t like: white Pomeranians, women in slacks, geraniums, strawberries, the harpsichord, Miró, tautologies, animated cartoons, Arthur Rubinstein, villas, the afternoon, Satie, Bartók, Vivaldi, telephoning, children’s choruses, Chopin’s concertos…’

What scope do you see for newer, more experimental forms of photography writing?

DC: Ha-ha, Barthes’ lists do look odd when out of context like that. (What was his problem with white Pomeranians and women in slacks??? Funny.) There’s always scope for new forms of writing, but a new form is only ever pursued when a desire and a necessity is felt, that for what ever reason it must exist.

But I’m not sure how much we need to read about photography at all. I’m always encouraging my students to read about other things. Politics, philosophy, anthropology, history, psychoanalysis, and about the subject matter of what it is they are photographing, be it trees, buildings, fashion or political protests. The American photographer Andreas Feininger published a book titled Photographic Seeing. This was in 1973, when the ‘serious’ study of photography was getting established in universities. He wrote:

‘There is no doubt that, as long as a student of photography is strongly motivated, i.e. seriously interested in a specific type of subject matter, he or she will eventually become a great photographer […] On the other hand, I have found again and again that people interested only in “photography” get nowhere. They go from photo school to photo school, take courses in photography, work as assistants to well-known photographers, read all the proper books, have an encyclopaedic knowledge of things photographic, own the latest and finest equipment – and never produce a worthwhile photograph.’

Of course it’s not a clear-cut either/or. The better writings on photography are also writings on other things.

TC: Yes, we see so many photographs of things rather than photography about something, anything. Is photography criticism not a great good then? Do you not consider it a noble pursuit?

DC: Put it this way…if photography isn’t photography when it’s only photography, the same goes for the writing about it.

TC: There we have it! In your introduction to Intimate Distance, Todd Hido’s recently-published monograph with Aperture, there’s a particular passage that really seems to encapsulate so much of what we’ve been discussing: ‘Living in the mind, pictures can never really belong to anyone. The unconscious does not recognise authors, origins, or destinations. What matters for imagery is resonance and restlessness.’

I was also intrigued by your idea of us all beginning in the ‘middle’. You write: ‘Making photographs is so often an act of recognition, conscious of otherwise, that what is before you resonates with things that came before. Those things might be direct experiences. They might be movies, picture books, music, or novels. We can never know for sure. And when we look at the photographs of others we are doing something similar: responding now through an elusive then. We all begin in the middle.’

DC: Well, we do all enter in the middle. Things were going on before we arrived, and they’ll continue after we’ve left the party. We pick things up where we find them and try to put them into some kind of narrative, be it history, or artistic biography, or autobiography. But it’s never clear-cut. For example, when we respond deeply to a work from the past – an image, a film, a novel – we are responding now. There is no time travel, and yet we know that the work could only have been made when it was made. So it’s not just that we enter in the middle… we are living in different time zones simultaneously.

TC: Could you tell me your favourite film, photo book, album and novel – those you would ‘choose as a pillow and plate, alone on a desert island’ (as Jeanette Winterson wrote of Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities)?

DC: Cinema was the first art form that really mattered to me, and it’s still the backdrop to much of my engagement with images, so I couldn’t choose one film. I could give you four. Robert Bresson’s Mouchette, Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo, Powel & Pressburger’s A Matter of Life and Death, and Tsai Ming-Liang’s Goodbye Dragon Inn. Tomorrow it might be another four. Photographic book? Walker Evans’s American Photographs. Album? Joni Mitchell’s The Hissing of Summer Lawns. Novel? Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway. ♦

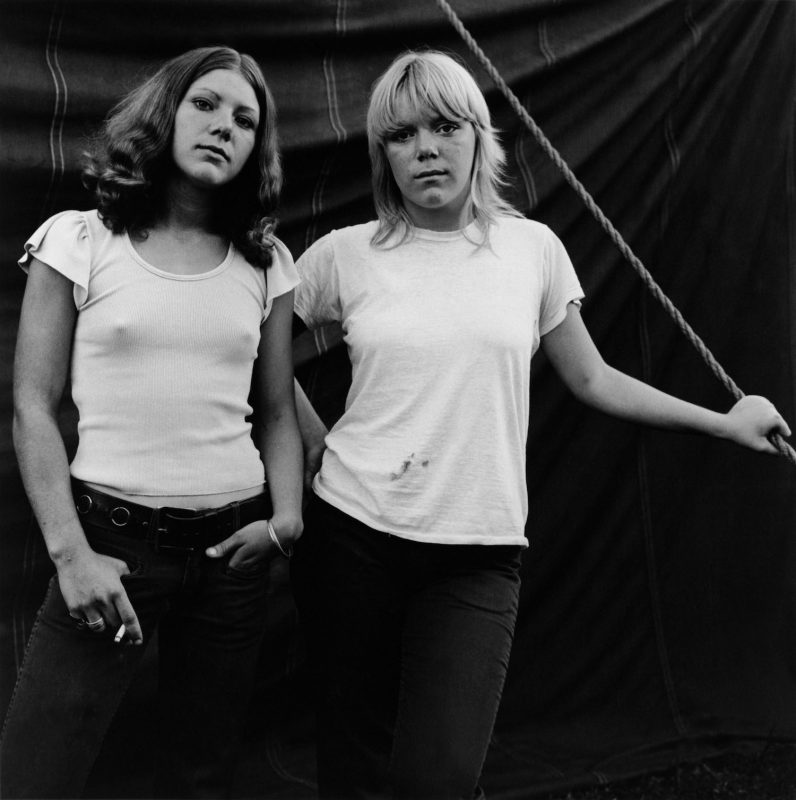

Image courtesy of David Campany. © Drew Sawyer