TJ Proechel

ADAM

Essay by Sara Knelman

In his 1985 book Suspects, David Thomson describes Smith Ohlrig, the deluded multimillionaire of Max Ophüls’s noir classic Caught (1949): “Unseen, he was imagined. Nonexistent, he was omniscient. Dead, or inert, he could be everywhere. He made a rare journey: uncomfortable as an author, he became a character for everyone, like the bogeyman or Santa Claus.” This is, as anyone familiar with the movie will know, an account of an ending we never see, a demise never scripted nor filmed. Rather than rehash what we already know of Ohlrig, and many other such ‘suspects’ whose lives we’ve watched flicker and fade, Thomson contrives their perpetual pasts and unseen futures. As he surveys some of American cinema’s most memorable characters (from Victor Laszlo to Kay Corleone), shadowy psyches and deep-seeded motivations rise to the surface. Hustlers and con artists, dreamers and drifters, corruptionists and redeemers, we might be just as compelled by raking light as by stark moral ambiguity. Their illusions – about themselves, about their desires, and most urgently about the visible world before them – seem to echo the larger illusions of cinema itself.

Thomson’s quest to find these fictitious figures in the midst of living darkly is a kind of journey in itself, an imagined road trip of encounters. Inspired, in part, by the same cinematic memory and noir aesthetic, photographer TJ Proechel sets out to find Adam, a real and prototypical modern-day con-man making his luck on foreclosed homes in the aftermath of America’s devastating housing crisis.

The backstory is prosaic enough. A young student just out of college, Proechel worked construction in Minnesota to make ends meet. In the wake of the housing crisis in the late 2000s, the work he was offered was increasingly on homes recently lost or repossessed. An earlier series, 2008-2009, documents some of these experiences. These are affecting, upsetting pictures of the homes themselves – unsuspectingly innocent from the pavement – of abandoned or hurriedly forgotten possessions – a stray photograph, a stripped mattress, a hand-written prayer taped to the wall – and occasionally, of those recently forced out.

In 2010, Proechel became the victim of a con, losing two months’ worth of wages after an owner of a house he was contracted to work on – a man who went by the name of Adam Burroughs – abruptly disappeared, taking investor money with him. The experience stayed with him, and as others wronged sought legal recourse, Proechel’s curiosity about the figure at the centre of the storm grew. What really happened here? Who is the elusive Adam Burroughs? Is there a truth to be uncovered amidst all these sleights of hand? Made over five years, Proechel’s photo-saga ADAM unfolds with all the trademarks of a noir classic: a shadowy drifter, a man wronged, obsession and pursuit, a search for the facts lurking behind so many projections and illusions.

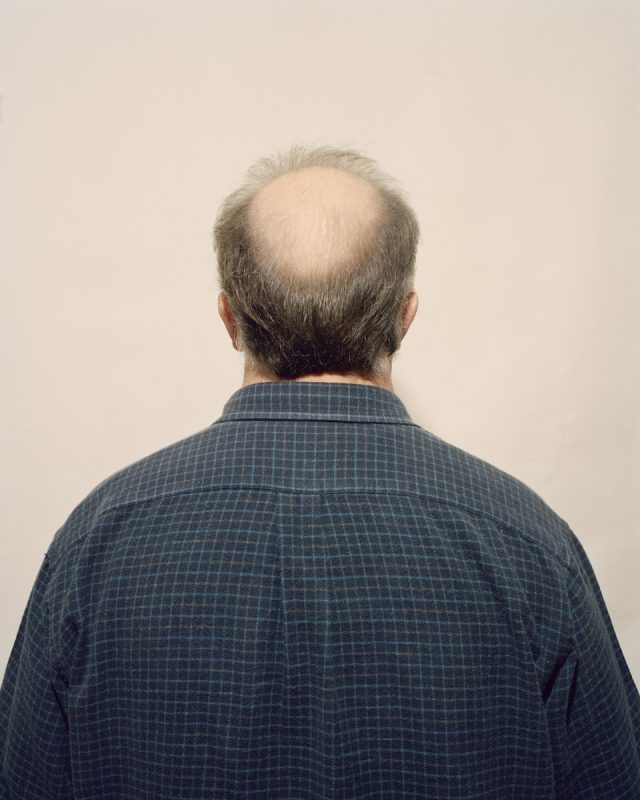

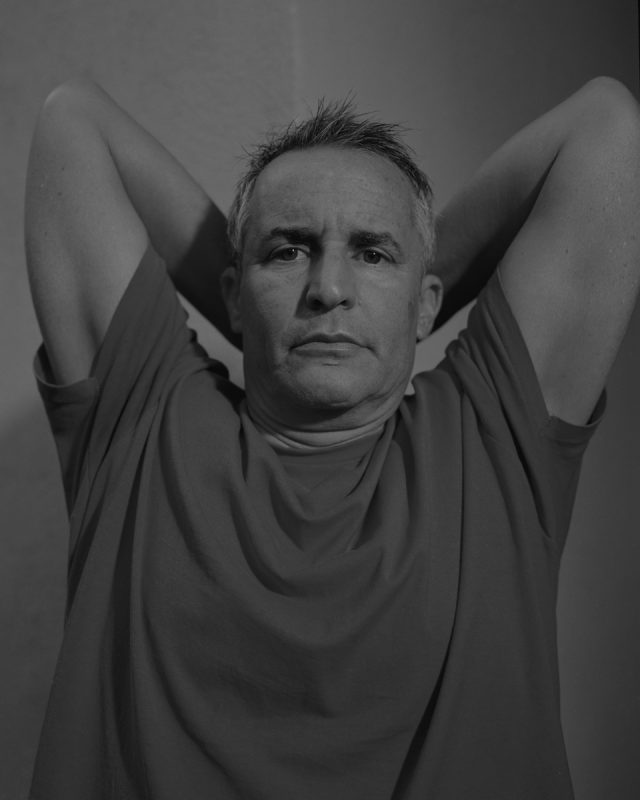

Proechel in fact ‘found’ Adam with relative ease, hiding in plain sight on the Internet, operating a real-estate blog and claiming to live in Southern California. Taking on the role of private detective, he set off on a series of road trips – a romantic vigilante with a car and a camera – to track Adam. Following clues and tips, Proechel finds stray traces across the country and ends, as American road trips tend to, at the edge, in this case the Pacific Ocean and LA. Proechel’s vistas of the journey feel cinematic rather than documentary, in part because of their careful cropping and saturated colours – a glistening quality of light that glamorises and seduces. Scattered portraits read like film-stills of unknown characters, and make use of jobbing actors standing-in for the real but absent stars. The mythic possibility and cinematic lore of Los Angeles, vivid here in explosions of palm trees lit like fireworks, provides a convenient destination, if not a tidy resolution.

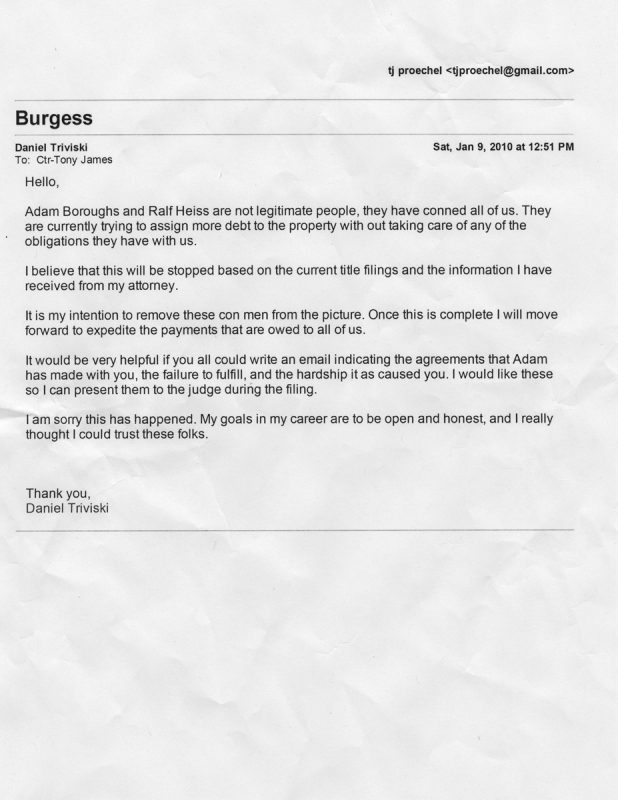

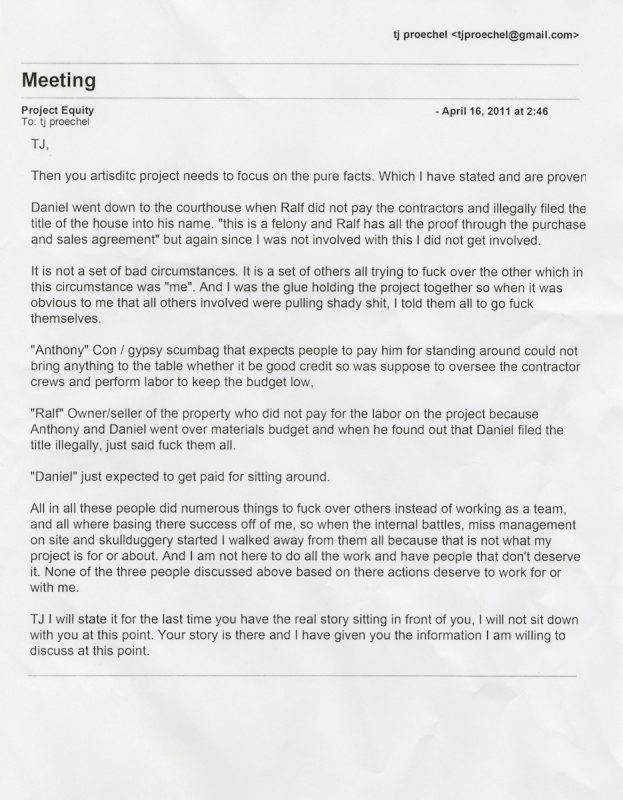

But the narrative is confounding; tentative, incomplete, hanging somewhere in the darkness that pervades so many images. Gaps are filled in by miscellaneous documents – evidence of the original property’s chain of ownership; Proechel’s half-completed work list from the job (‘fix busted tile’, ‘adjust door lock’), and, crucially, a stream of emails, a real-virtual exchange between Proechel and Adam. The suspect surfaces, if only online, to confess his innocence: “It is not a set of bad circumstances. It is a set of others all trying to fuck over the other which in this circumstance was ‘me’. And I was the glue holding the project together so when it was obvious to me that all others involved were pulling shady shit, I told them all to go fuck themselves.”

Adam’s notes also express an acute anxiety about Proechel’s project – of this public interpretation of himself, a character, perhaps the villain, in this unfolding story. The exchange reads like a parallel fiction and a counter-plot, in which Adam seems completely unbelievable and deeply real.

Like Thomson’s musings, Proechel’s ADAM is neither fantastic speculation nor documentary truth. As evocations, both images and text draw on our collective memories of specific and archetypal places and lives, on our insistence on narrative convention, and on our inclination to believe and imagine. Suspects, intriguingly, includes no film stills – no recalling of iconic shots or lauded celebrity turns. The only two images in it are, in fact, reproductions of still photographs: on the cover, Walker Evans’s Torn Movie Poster, 1930; and tucked in opposite the inside title page, Wright Morris’s Reflection in Oval Mirror, Home Place, Nebraska, 1947. Truth, they both seem to suggest, may be less important than its telling. “Is there construction,” Thomson asks, by way of introducing Vertigo’s Scottie, “or do we live in unshaped turmoil? Is the mass of human creatures just random contiguousness, an impossible tottering pile or is there an elegant cellular pattern in human association…inspired by eternal forms of feeling and relationship – love, jealousy, curiosity, vengeance, desire, incest, ambition and fear of falling – flexing and pulsing through time and space, like the brain waves of sleep?”

Proechel’s ADAM is an answer, and a quest for an answer. ♦

All images courtesy of the artist. © TJ Proechel

—

Sara Knelman is a writer, curator and Assistant Professor at the School of Image Arts at Ryerson University. She has worked as Talks Programmer at The Photographers’ Gallery in London and Curator of Contemporary Art at the Art Gallery of Hamilton. She writes about photography for Aperture, Frieze, Photoworks and Source: The Photographic Review. She collects pictures of women reading and lives in Toronto.