Tom Griggs and Paul Kwiatowski

Ghost Guessed

Book review by Natasha Christia

For her piece In Free Fall: A Thought Experiment on Vertical Perspective for e-flux journal #24, 2011, Hito Steyerl writes: ‘Imagine you are falling. But there is no ground. (…) Paradoxically, while you are falling, you will probably feel as if you are floating – or not even moving at all. (…) As you are falling, your sense of orientation may start to play additional tricks on you. The horizon quivers in a maze of collapsing lines and you may lose any sense of above and below, of before and after, of yourself and your boundaries. Pilots have even reported that free fall can trigger a feeling of confusion between the self and the aircraft.’

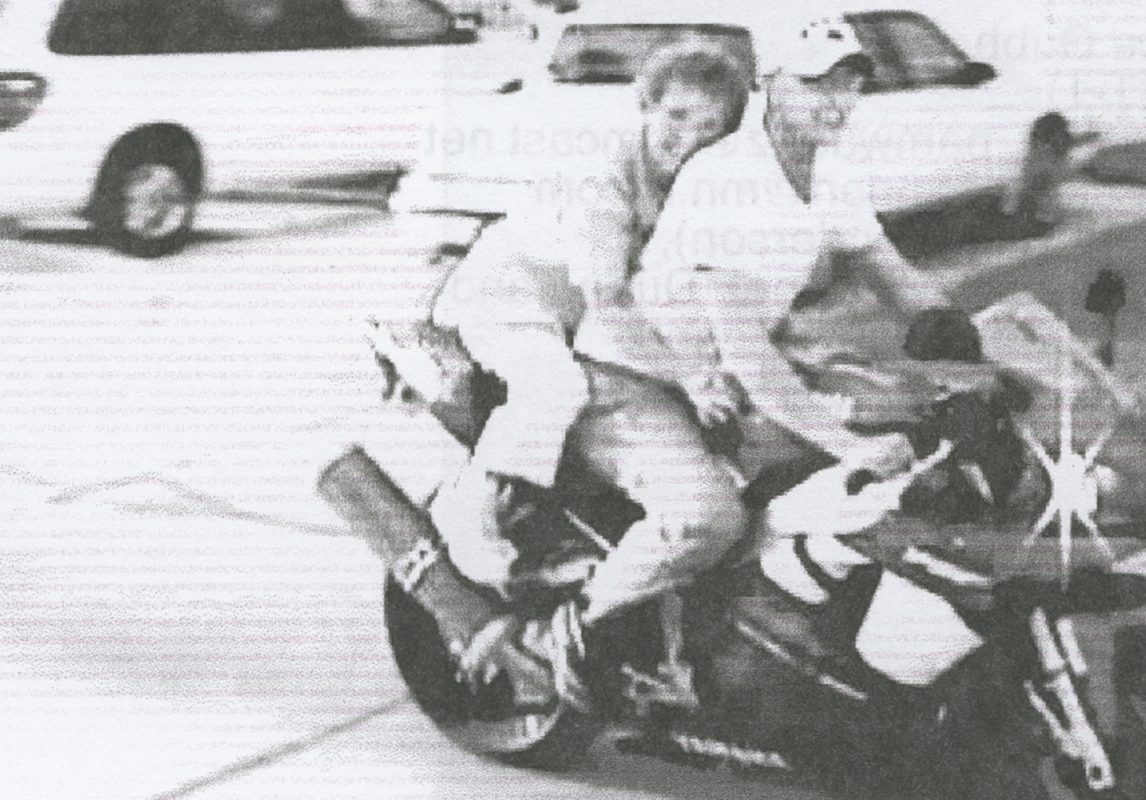

Ghost Guessed by Tom Griggs and Paul Kwiatowski is a brilliant meditation on disorientation amidst a groundless world of increasing digitisation, expanded horizons and prolonged absences. In their book, the voice of a narrator is deployed to bring together two stories centred on the theme of loss: firstly, the tragic accident of a young pilot, Grigg’s cousin Andrew Lindberg, who crashed while on his way to a hunting trip in northern Minnesota in 2009; alongside the disappearance of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 in 2014, undoubtedly one of the greatest mysteries in the history of modern aviation.

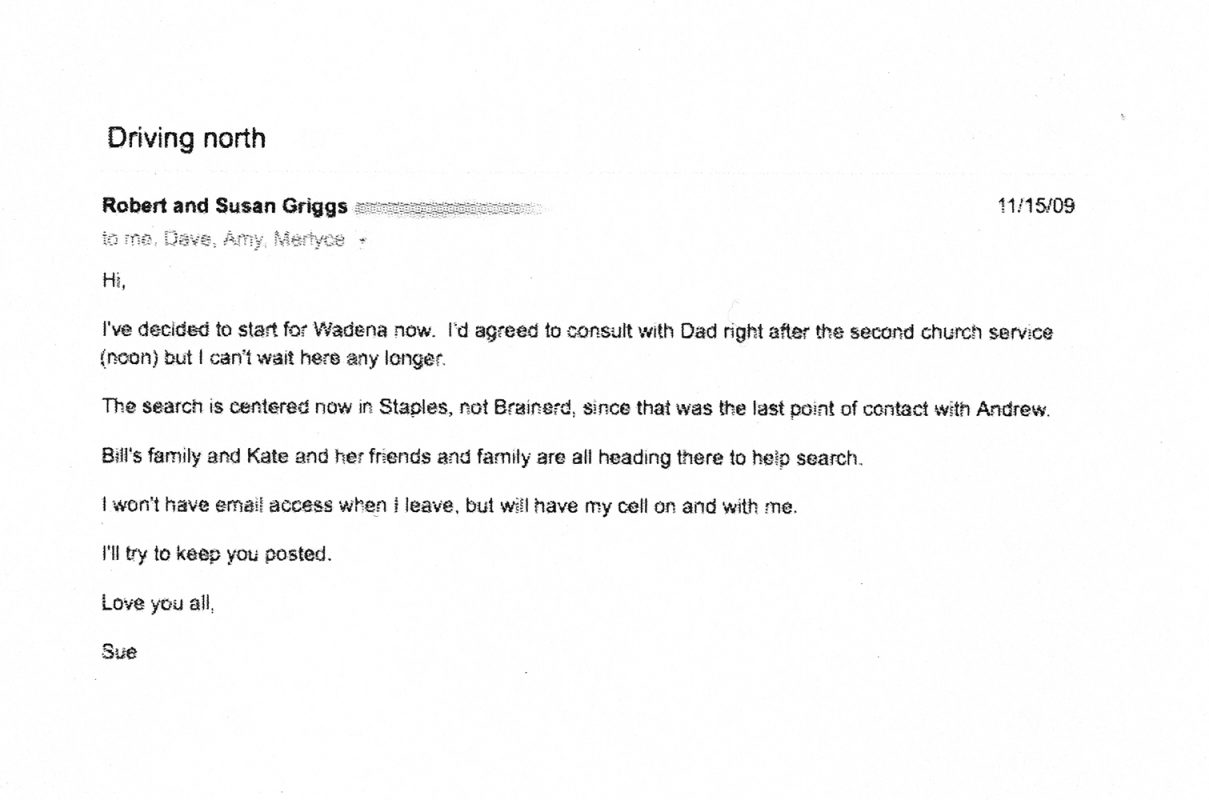

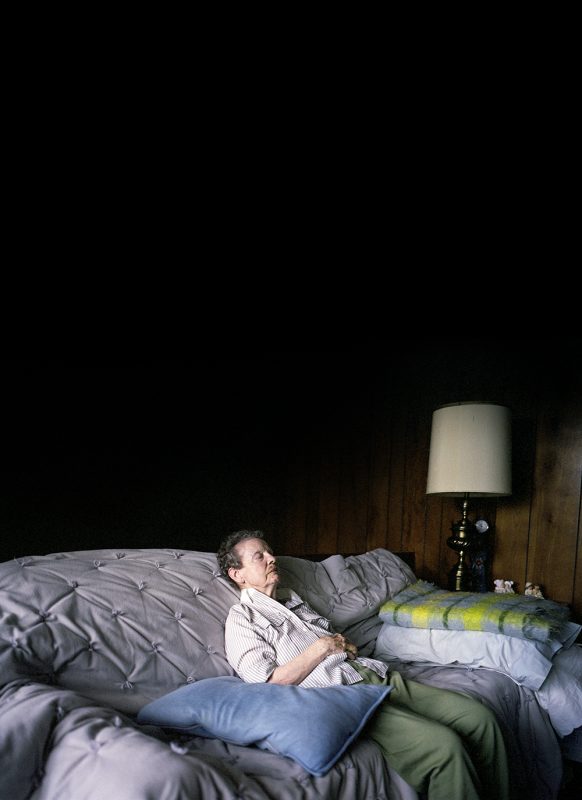

Combining intimate prose with photographs, Ghost Guessed examines the after-effects of these unfortunate incidents. It looks through the multiple emotional strategies people employ to process absence caused by death in an era of high-tech visual media; images here are seen operating both as a means to validate facts and as cradles of comfort insulated from pain and self-delusion. Three chapters divided in subsections arrange the project chronologically. ‘Vanish’ awakens memories of the two accidents, their media coverage and impact; ‘Search’ focuses on the narrator’s failed attempt to reconnect with his family through an unsuccessful return to the crash site; and ‘Return’ is a flashback to a trip to Kuala Lumpur, presumably three weeks after the news of MH370 broke.

Ghost Guessed adds up to an alluring fictional essay on the visual culture with which Griggs and Kwiatowski grew up. Long passages of text alternate loosely with a variety of registers that encompass the visual archaeology of the last 30 years: Family photographs, stills extracted from home videos, forensic reports from the crash scene, press images, TV screens and aerial photography offer one level of imagery, in tandem with the authors’ own photographs or digital collages. On the one hand they set the tone for dealing with demise and pain, but at the same time, they address how media – from domestic video cameras to today’s online streaming – have been paramount in creating our rational and metaphysical understanding of the self and the exterior world.

Ongoing digitisation and its intrinsic technological and aesthetic modes have been at the core of the skilful intertextual construction of Ghost Guessed. What began as a sporadic Skype correspondence between the two artists turned into a poignant co-authored memoir of life interconnections and synchronicities. The revelation of Andrew Lindberg’s accident during the conversations provided the breakthrough from theory to life, triggering a series of strange coincidences and life experiences, such as an unexpected opportunity for Griggs to undertake a trip to Malaysia, and his decision to revisit the crash recovery scene. Project and life started to collide.

Ghost Guessed eloquently addresses the pronounced shift of our times from the zapping condition, where screen and spectator are still physically and ontologically separated, to a form of second life, where orchestrated reality literally takes over. As early as the eighties, Andrew Lindberg’s grandfather is the first of the family to step into an alternative reality. Enclosed in a flight simulator during an aviation convention, he manages to channel his frustrated dreams of becoming a pilot without any risk of failure. Later, it is the narrator who undertakes the same route as the MH370. Surrounded by a screen in a controlled airspace chamber at Pavillon, one of Kuala Lumpur’s most popular shopping centres, he is able to position the aircraft safely back on the runway, rewriting history and restoring hope. If simulators perform it explicitly, this euphoric re-enactment of fate implicitly undercuts the whole Ghost Guessed. In order to make sense of reality’s haphazard and heavy events, the protagonists resort to social networks, snapshots and amateur video cameras –‘their eyes wandering non-stop through floods of images’. Eventually what is real has to take place in the realm of the virtual.

And yet the very thing that gives the overall narrative its linchpin is that which is impossible to reach. ‘Located deep within the wilderness of the White Earth Indian Reservation’, the event has not been recorded. The day Andrew’s body is recovered the gathered family is not allowed access to it. The body cannot be seen; no image is produced. ‘Years later, on the drive to return to the crash site, the narrator is lost and unable to make the photograph. By the time he is almost there, it is too dark’. Arriving at the scene neither ensures the success of the experience nor does it make him feel closer to his family. Ghost Guessed deals with this paradox – the excruciating albeit redemptive resistance of the fact. In the aftermath of the accident, the narrator, ‘floating through time with no structure’, appears watching for hours the lives of family and friends through social media. There is always the screen mediating, as if the relieving pure truth lay unreachable in the blind algorithmic parts of the simulation cabin.

In her video essay In Free Fall (2010), Hito Steyerl examines how the paradigm of linear perspective today is currently supplemented by groundless vertical perspective. Likewise, Ghost Guessed is replete of ‘vertical cities that measure the distance to the horizon in blocks’, and of views from above or towards the sky. This condition of verticality is even further accentuated towards the end of the book, pointing to the ultimate fragmentation of experience in a hyper-reality devoid of foundational schemes as Kuala Lumpur evokes a claustrophobic glass shimmering dreamscape. Under its discoloured sky, any sense of orientation is disrupted and multiplied into a million pieces. Even the views of Hawaii from the pilot’s cabin end up looking as a simulated landscape; the horizon is melting before our eyes.

‘Blue skies, clear skies, everything is ok’. A fascination with birds, flights, and clouds – both natural and virtual – too is vividly apparently in Ghost Guessed. Different cognitive systems, such as astrophysics, meteorology and religious omens, hint at solutions to enduring questions but these expectations crash against the narrative’s disquieting mix of conspiracy theories and endless media speculations. Extracted from video stills of jet flight crashes, the collage of the four planes in the middle of the book signals the mediatised hijacking explosions as it was exemplified in Johan Grimonprez’s glorious Dial History (1997). The sky is consolidated as the sanctuary of destruction where our more precious memories are anchored to impossible images. Up there, aside from the unlimited time of fall, there is no stable paradigm of orientation onto which we can hang. As Paul Virilio once remarked, each technology invents its own catastrophe, and with it a different celestial insurance. Ours is the permanent vertical fall. ♦

All images courtesy of the artists. © Tom Griggs and Paul Kwiatowski.

—

Natasha Christia is a writer, curator and educator based in Barcelona.