Valeria Cherchi

Some of you killed Luisa

Essay by Emma Lewis

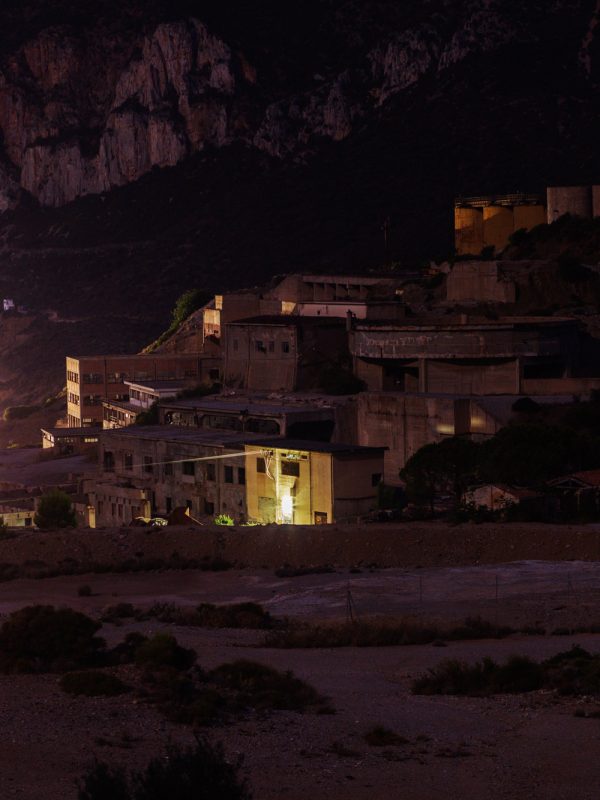

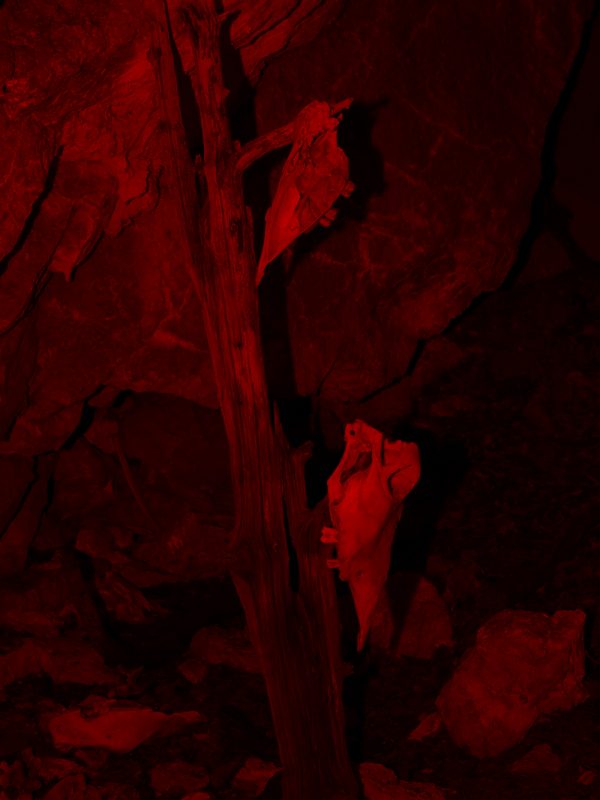

On 16 June 1992 a priest from the Sardinian region of Barbagia received an anonymous telephone call guiding him to a remote mountain road. There he found a package containing the following: a photograph of six-year-old Farouk Kassam, the upper part of the child’s ear, and a letter threatening his demise in horrific circumstances. Kassam, the son of hoteliers, had been held hostage for five months, in caves and other mountain hideouts. His kidnapping was by no means unusual: close to 200 people were held for ransom on the island between the 1960s and late 1990s. But his story precipitated an unusual wave of defiance against the ‘Anonima sarda’, the bandits who operate independently but in accordance with omertà, or code of silence. Hundreds of locals placed ‘Free Farouk’ signs in shop windows. White bedsheets were hung from balconies as a symbol of solidarity. Pope John Paul II appealed for the child’s release.

On 10 or 11 July – reports differ – Kassam was let go. Matteo Boe, one of Italy’s most wanted, was among those convicted of his abduction. Twelve years later, Luisa Manfredi, Boe’s fourteen-year-old daughter, was shot dead as she hung up washing outside her home. No one was ever charged for her murder though there remain several different theories as regards to the motive.

Most children, at some point or other, experience a fear of being taken from their parents. For Sardinian-born-and-raised Valeria Cherchi and her peers, this fear had a different gravitas. Cherchi was about the same age as Kassam when he disappeared, and has vivid memories of the white sheets that summer. She recalls, too, watching the news reports of Manfredi’s murder, and observing the contrast between the portrayal of her mother, Laura Manfredi’s, grief, compared to Boe’s. Over the years, Cherchi’s preoccupation with Sardinia’s kidnapping phenomenon intensified. Wishing to learn more about the history of her home island and – somewhat idealistically – ‘decode the complex structure of the kidnappings’, she began researching Barbagia’s small and closed communities in relation to omertà. Over time her focus narrowed to, as she describes it, ‘the desperation of two mothers: one unable to control the fate of her young kidnapped son, and the other unable to find justice for her murdered daughter.’ Both had pleaded for people – women especially – to speak out. One day, Manfredi walked into her town square and graffitied in broad daylight: ‘Qualcuno di voi hanno ucciso Luisa’: ‘Some of you killed Luisa’.

Part of the narrative around these events, of course, is that there is no reliable narrative. News reports from the time note the uncertainty surrounding the chronology on the 10 and 11 July. ‘Almost immediately after the boy’s release,’ described one New York Times article, ‘questions and discrepancies began to intrude.’ Details had to be ‘pieced together’ by the police, the victim and his family. According to Cherchi’s written accounts of her interactions with the Barbagia people, inconsistencies remain a key characteristic.

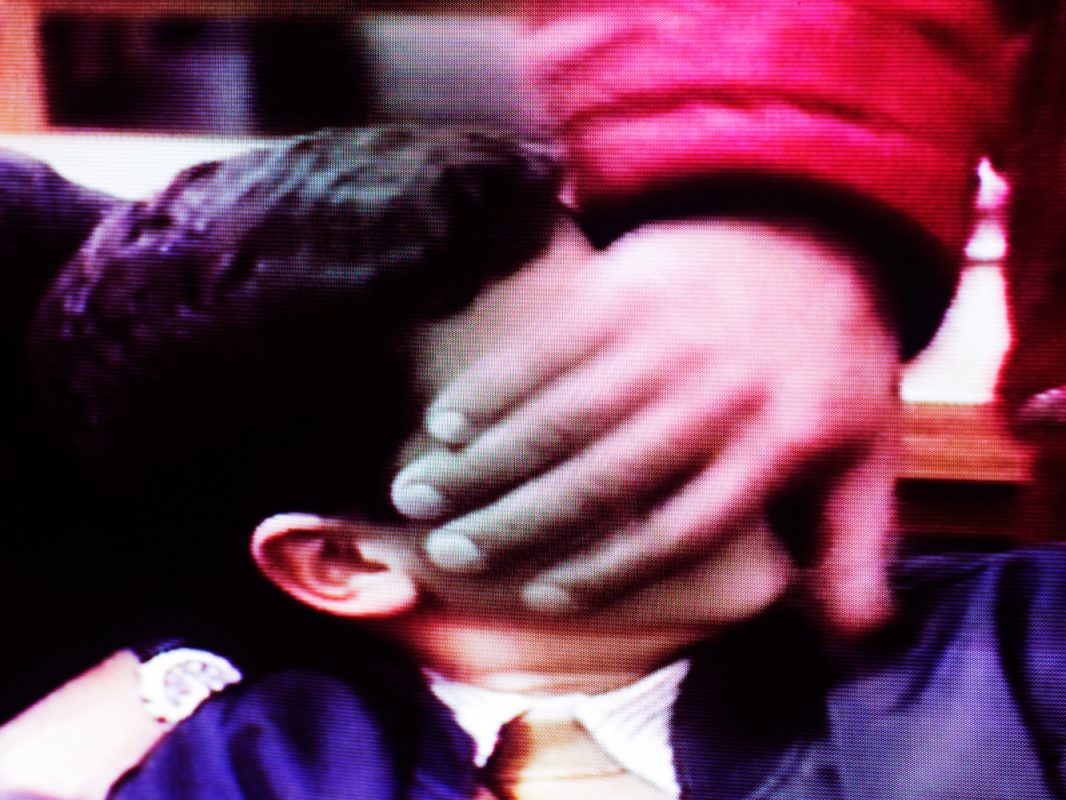

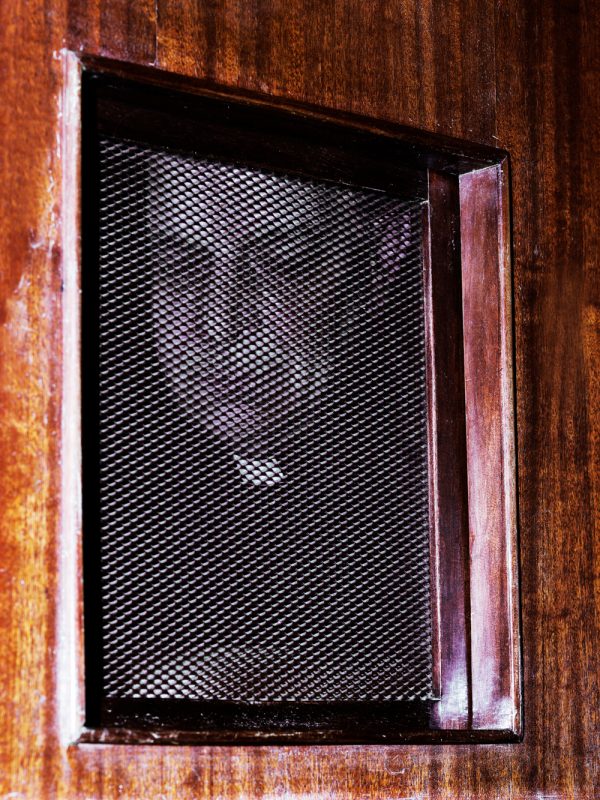

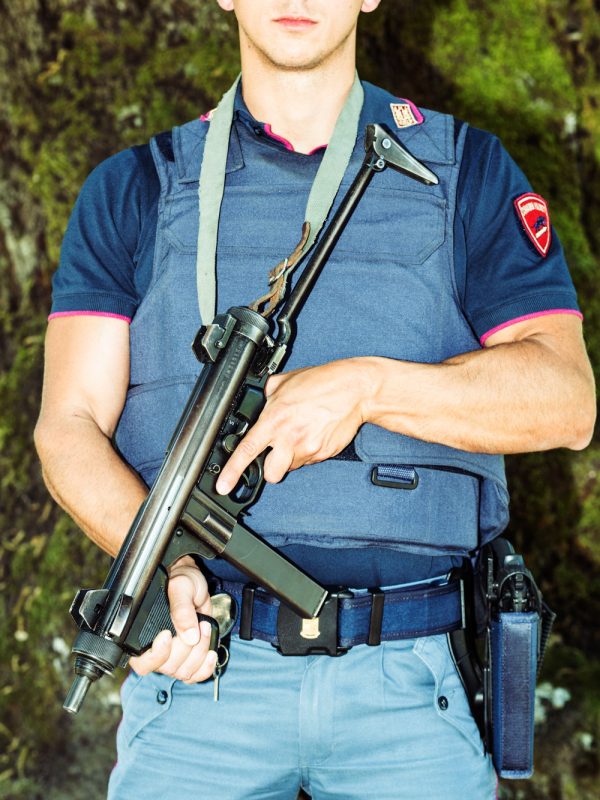

It is apt, then, that Some of you killed Luisa takes the form that it does: a combination – piecing together, if you will – of television and VHS stills; staged portraits; mise-en-scènes inspired by Cherchi’s own memories and those of the kidnapped; and reports of her investigation, including transcripts of oral testimony by kidnap survivors and those in the local community. The mood is unsettled, unsettling; the atmosphere enigmatic. This approach to conveying real-life events, prevalent in contemporary photography for a number of years now, is one that I think of as a kind of collaged approach to the documentary form: assembling a many-layered, multi-textured picture from disparate sources that may not otherwise be in close proximity. Regine Petersen’s Stars Fell on Alabama (2013), Jack Latham’s Sugar Paper Theories (2016), and Mathieu Asselin’s Monsanto: A Photographic Investigation (2017) are a few acclaimed examples. Often executed over a long period of time, the photographer embedded in the community, a case could also be made for them operating as part of the cult revival of investigative and long-form journalism.

And yet like the collage elsewhere in art, literature, and documentary film, this approach remains deeply subjective. Archival material is, by definition, decontextualised; selected or omitted according to personal criteria. This is the narrator’s prerogative, to convey the story that they wish to tell, in the manner in which that they wish to tell it. It almost goes without saying, too, that bringing a story alive after the fact requires imaginative use of non-documentary material – be it archival, staged or otherwise.

If this collage form grants freedom – in treatment of content, and in style – it also highlights the photographer’s responsibility to their audience and subjects. Certain questions have to be asked. What does it mean, for example, for a photographer to state that they are ‘investigating’, especially where criminal activities are concerned? What is motivating the protagonists to speak out? Is this the only the way that they feel their voices will be heard, and if so, whom do they believe to be listening?

The most robust examples of such projects – and I include Cherchi’s, and the three aforementioned, in this – address these questions by making the photographer’s position clear. Asselin’s project is, without ambiguity, an exposé. Latham and Petersen, by contrast, each state that their primary interest is photography’s relationship to the events in question. Some of you killed Luisa is successful because Cherchi makes it clear that she is delving into a subject that has needled into consciousness for decades. The inclusion of stills from her own family’s home videos – a nod, she explains, to her pained awareness that her life continued, while Manfredi’s did not – is a particularly effective way of introducing her presence. Likewise her reports: by turns factual statements on the how, why and when, of her research, and poetic but lucid accounts of time spent with Barbagian communities, as she navigates the regional differences, and the secrecy. As an outsider, this is fascinating: mysterious without ever becoming nebulous. One gets the feeling of being guided through the dark, almost, as Cherchi shares what she knows about this unknowable place – and what she is only just beginning to piece together. ♦

All images courtesy of the artist. © Valeria Cherchi

—

Emma Lewis is an Assistant Curator at Tate Modern, where she organises exhibitions and displays and is responsible for researching acquisitions for Tate’s photography collection. Her book Isms: Understanding Photography was published by Bloomsbury in 2017.