Gloria Oyarzabal

Usus Fructus Abusus

Exhibition review by Sergio Valenzuela Escobedo

Sergio Valenzuela Escobedo examines images from Gloria Oyarzabal’s new work in progress, to interrogate the idea of the museum as a mere neutral or beneficial protector of the objects and artefacts it owns, currently on display as part of Fotografia Europea in Reggio Emilia, Italy, and Romo Kultur Etxea during GETXOPHOTO in the Basque Country.

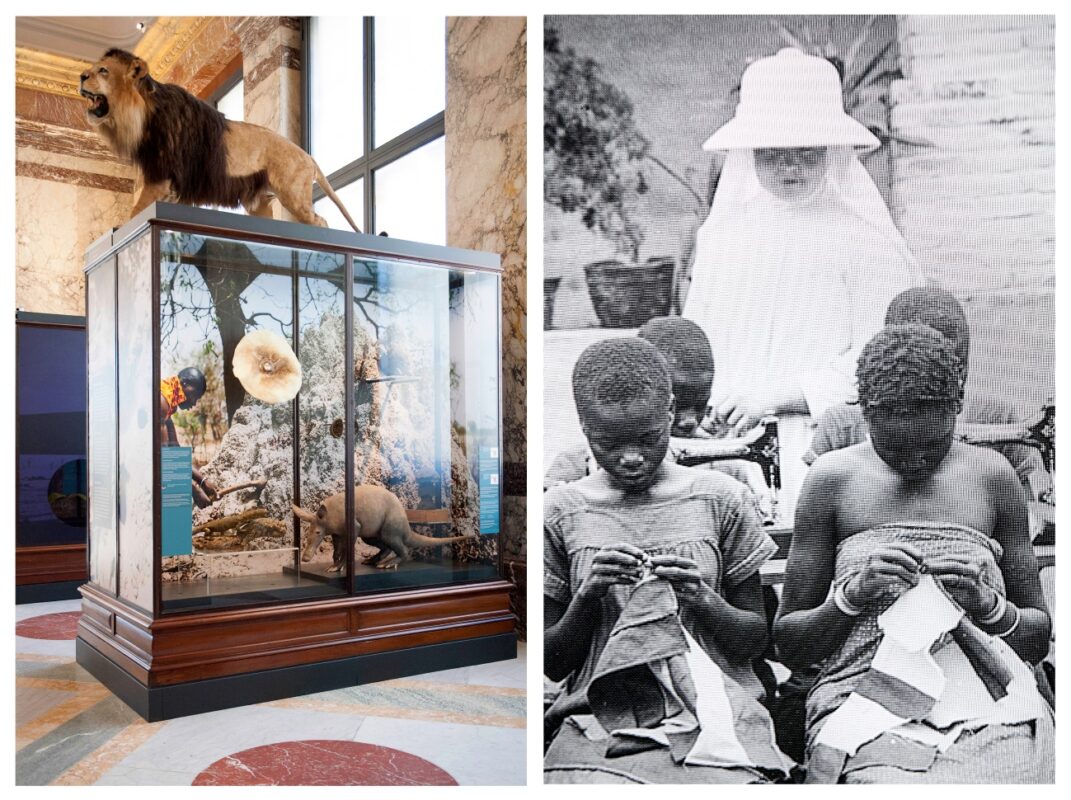

Usus Fructus Abusus is an exhibition by Gloria Oyarzabal, selected as part of the Open Call for Fotografia Europea 2022 in Reggio Emilia, Italy. It draws attention to some complex issues considering the relationship between aesthetics, institution and race, doing so in the guise of what the artist calls “a reflection that starts out from a critique of the museum, viewed as an act of historical prevarication on the part of the winners over the vanquished”. Analysing the idea of the museum means rethinking the provenance of the collections, but also understanding the idea and consequences of collecting, conserving and protecting from a Western, white perspective. Criticising the “museum mission” in one of the countries in which the concept of the museum was born is a worthy mission, even more so when the artist admits to being a white privileged woman on the side of the “winners”.

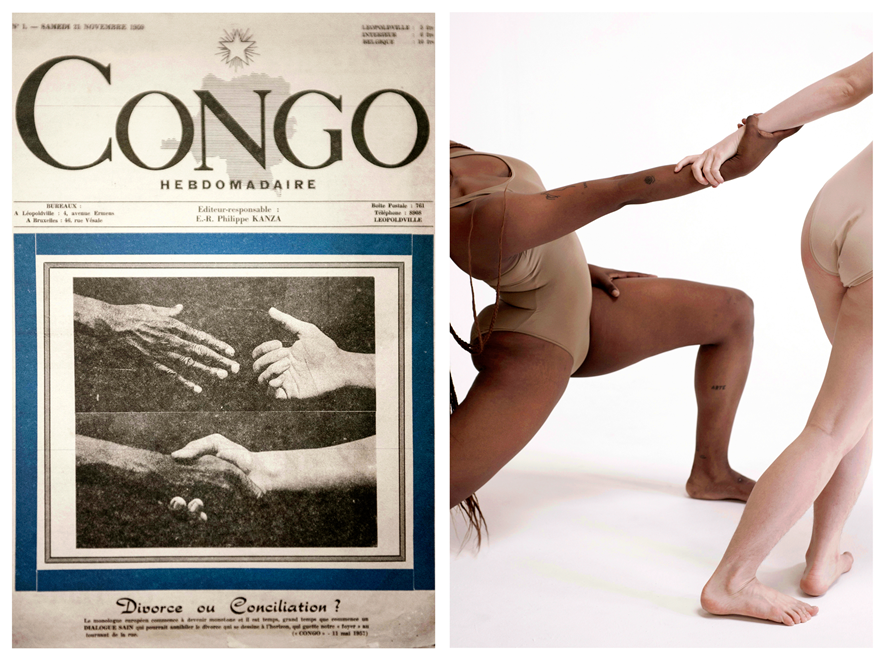

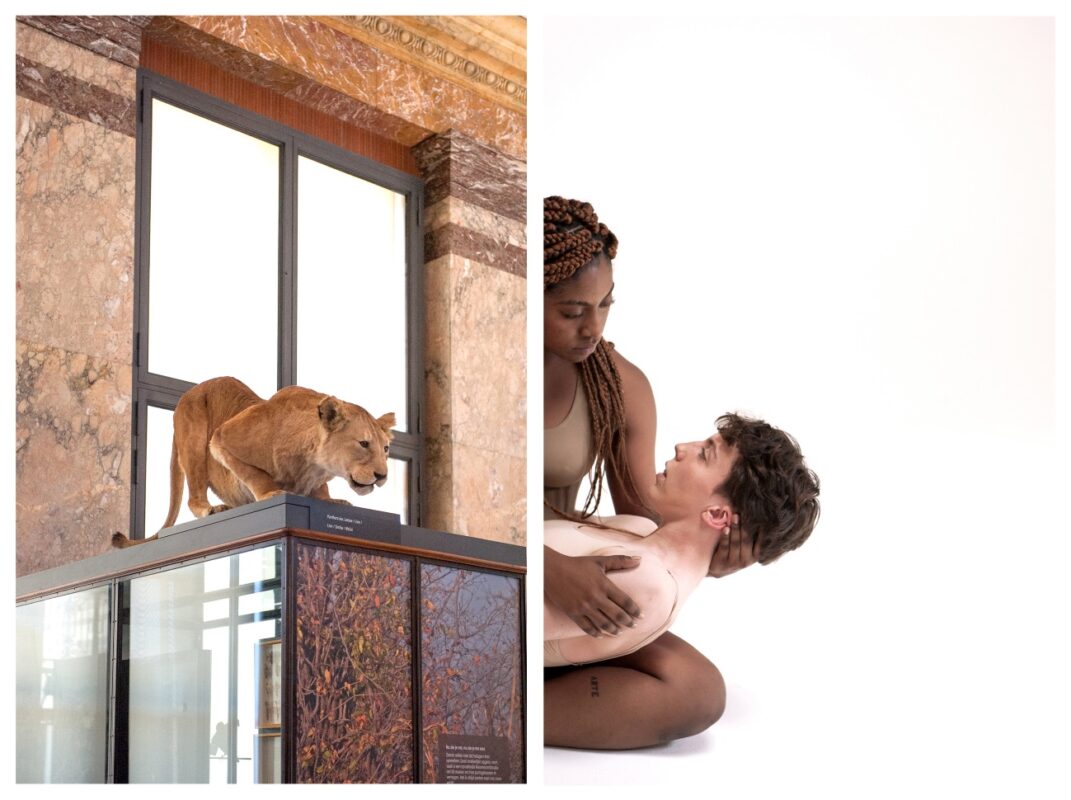

As a starting point, we find the painting La Blanche et la Noire (1913) by Félix Vallotton. We know that it is a mise-en-scène because it is possible to recognise the original printed in a small postcard and glued in the sceneography. It is inspired by Édouard Manet’s Olympia (1863), which, at the same time, takes its cue from Titian’s Venus of Urban (1538). The idea here is not to make an umpteenth commentary on Manet’s painting, but to understand the consequences of using a Western painting as a model for a photographic project. Oyarzabal appears to delve into the “nude” as one of the official genres of works kept in museums. However, the omission of naked male bodies specifies the framework: the use and abuse of the nude female body in Western representation in 19th century. It is also worth mentioning that the omission of Black bodies in the history of Western art serves to underline the fact that many of the Black models are unnamed, exoticised and forgotten.

When using a painting as a model, its whole history inevitably comes with it. As we know, history has not always been told accurately, with minority perspectives on nation-building typically underrepresented. How fraught and crucial is the role of the museum then in sharing histories and providing context and meaning? For example, the exhibition Le Modèle Noir de Géricault à Matisse (2019) at the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, allowed the audience to discover the name of Laure, the Black model who appears in Manet’s painting. The exhibition demonstrated that the African, Caribbean and Afro-American diaspora is an indisputable fact of an institution devoted to culture and, in particular, to ‘Paris, Capital of the 19th century’ to quote Walter Benjamin.

Whilst, in the Musée d’Orsay exhibition, annotations detailed all the changes in the titles of the original paintings by the Black model’s name, Oyarzabal uses national flag installations: six banners introduce the audience to an artform that deals with the display and regulation of hereditary symbols employed to distinguish individuals, armies, institutions and corporations without any information. Oyarzabal’s omission of the names of the models raises a question: who are these unknown, naked women who adopt the staging in a photograph that copies a Western painting?

Here, the mise-en-scène becomes dangerous: it is difficult to know if we have to consider this series of photographs as fragments of a fiction, or representations of a constructed documentary. Regardless, perhaps Oyarzabal should show the ideological construction that most ethnological photographs contain. This is an interesting affair when it comes to analysing the collection of plates brought back by scientific missions. They become clear examples of a colonially organised system of representation, showing scenes that correspond more to the images colonisers wanted to see than to reality. They are themselves the image of the aesthetic scaffolding that the white man designs to represent the people from beyond, by doing so the ethnographical collections allow us to talk about scenes, sets, actors, directors, as well as the backstage, which could also give to this series a better understanding using the re-enactment as an artistic tool.

It’s well known that during the Renaissance, the concept of the museum appeared and marked a step towards a more scientific understanding of the world. The “Cabinet de Curiosité” was created by objects that were brought from all over the world. This is directly related, not only to the technical and economic capacities of the richest kingdoms to travel and come back from “exotic” places, but also to assume the philosophy that the scientific mind is destined, by an inexorable law of the progress of the human spirit, to replace theological beliefs and metaphysical explanations. But science has always been at the service of politics. The artefacts found in European museums are not only proof that cultures existed in remote places, but they are faithful witnesses to the fact that these places were now named and conquerable.

Consider how Oyarzabal shows an interesting set of images of empty museum cabinets. Whilst Oyarzabal’s purpose is somewhat unclear, the aim seems to be to shed light on the issue of the museum’s restitutions of what the European colonialists plundered and ransacked, pondering who might now judge and repair the fractures of history – a brave task when the same institutions that Oyarzabal criticises are the ones that have written the norms and rules on how to promote decolonisation via such means. Let’s also not forget that states do not orchestrate such returns without diplomatic exchange; action of this kind continues to serve heavy financial, industrial and military interests. The actual question is not if white empires should or shouldn’t give back the artefacts with the risk of leaving European museums empty, but about the real exchanges that the cultural industry will generate in their restitution practice. Are they really working for a common future?

On the other hand, it is interesting to study how African museums will exhibit these objects. Whilst museums with ethnographic collections are aware that they have to change, new African museums largely look identical to their European counterparts. Since the 1990s, many across Europe have closed, been defunded or packed up their inventories. Others have become museums that embrace other cultures by acknowledging their colonial histories to varying extents, the most critical example being Belgium’s Royal Museum for Central Africa (where Oyarzabal’s images have been taken). Reopening in 2018, the museum has chosen to retain the original presentation of exhibits with explanations as to their historical contexts. So, instead of giving the art back, they inform visitors that all of their objects are stolen. And by providing this interpretation, the scars of the terrible past of Belgians in Congo should become visible, as well as their responsibility or disavowal of their guilt by replacing the void with new artefacts hiding the history, again under the light of the glass vitrines. This how the void should be read in Oyarzabal’s images. But let us not be naïve, the latest trend is making ethnology a thing of the past by opting for highly beautiful display presentations. This is a key moment for the future of Oyarzabal’s ongoing project (it is noted that it is ‘work in progress’): the Dogon join the ranks of the Mona Lisa. So, what happens with the art market then? We know that some museums today buy from auctions, so what will happen if they have to return items because of their problematic provenance? Will this market lose its appeal?

Perhaps this commercial aspect is of no interest to Oyarzabal who addresses the myriad ways in which museums have been and often remain the beneficiaries of Europe’s violent expansion and exploitation, as well as the purveyors of the stereotypical imaginary. However, this seems to be one of the problems facing museums today. Certainly, the concept of the museum, dating back more than 100 years, has created ideas of identity and preserved the most precious treasures of the most powerful nations, but there is something else we tend to forget; it is not common knowledge that the beginning of collecting by European powers in Africa is strictly related to a small cultural clause born after the Berlin Conference that protects anyone – missionaries, scientists and explorers alike – who all collect objects. This is why, from the 1880s, springing up all across Europe were either huge departments of ethnology in existing museums like in the British Museum, whose collections mushroomed, or the remarkable new buildings specifically built for these new collections, like the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadero, Paris. Between European powers meeting in Berlin to decide how they would divide Africa and the construction of empty museums helps give a new understanding to the symbol that evokes the void of the empty museum cabinets in Oyarzabal’s work. The purpose of Oyarzabal’s research is to review the relationship between ethnology and museum collections from a largely plundering colonial present, to contrast the idea of museums as creators of imaginaries and to show them as a form of institution that is not, nor has it ever been, a mere neutral or beneficial protector of the objects and artefacts it owns.

Elsewhere in the exhibition, two women find themselves dancing by way of staged photographic scenes. Their body-image reminds us of the work of Faith Ringgold, who balanced stories of harsh realities with hopeful visions; her Dancing in the Louvre (1991), preconfigured Beyoncé and Jay-Z’s takeover of the museum decades later, straddling R&B and rap in the great galleries where the Victory of Samothrace, the Venus de Milo and the Great Sphinx of Tanis are located. The assault on, and appropriation of, the museum world by popular culture makes it a flagship of Western society that must be seized in the reversal of symbols. At the same time, the clip makes the museum the last bastion of the inequality of wealth distribution. The Carters do not in any way overturn the established order and the Louvre can surely only benefit from this global spotlight.

Certainly, many of the interventions based on artistic reappropriation emanate from a Black culture that enters the conflicting time and paradoxical space of the museum institution. But under a “time of transfer”, what institutions are doing to rethink the monumental history of its collections is not interesting anymore, because the loss of animism is not going to be cured with the devolutions of objects from the past. It is the side of history that we see all the time, but which does not show itself: after all, the architecture of power has no image. But if the counter perspective would no longer focus on the victims but on the perpetrators, presenting the troubling history of whiteness, describing its lies, paradoxes and oppressive nature, maybe it will take shape. Because if we follow the same direction, the risk is to reinforce and recentre white anger. Oyarzabal presents us with the relationship between white and Black bodies but it is only the beginning of the performance that she allows us to see. We will be watching to see how she finishes this dance.

Western magic presents an unjustified omission: European science, so to speak, already installs a primitive animism. Only it is Greek and is read as a literary effect. The myth of the Platonic cave installed in history the role of the simulacrum, on the one hand, and on the other, the story of the potter’s daughter of Corinth enabled representations of our desire for that very representation. Let it be clear that the aim is not to critique the scientific research that speculates on the mathematical nature of phenomena. I am suggesting that it is the children of those early consumers of myths, who have travelled the seas in their ships, to have at their disposal the objects and images of other bodies in spite of themselves. Then there would be no such European science, but a mythology of progress accompanied by mathematics dictating the fate of the mechanical images attached to the epic navigations essential to every nation with colonial pretensions at the end of the 19th century. Oyarzabal’s ambition is to make a work that exposes all the nostalgia of the mythical, the epic and the sacred. Borrowing the words from a particular high school student once residing Reggio Emilia, who insisted so much on nostalgia for the sacred and how it remains attached to ancient values, Pier Paulo Passolini said: ‘I sometimes have the feeling that they are victims of an artificial acceleration, of an unjustified, premature oblivion…’ [i]

Albert Camus wrote: ‘We live in a desacralised history.’ [ii] The relationship between Black bodies and white bodies that pull forcefully from one side to the other in Oyarzabal’s photographs represent the spirit of change; it is the character of modernity in rupture with the whole ancient world. White Western thought often arrives to desacralise. This dance can be approached as a reliquary in which Europe appeases the anguish that has haunted it for centuries: animism. ♦

All images courtesy the artist and Fotografia Europea © Gloria Oyarzabal

Usus Fructus Abusus is on display at Galleria Santa Maria, as part of the Open Call for Fotografia Europea 2022, Reggio Emilia, Italy, from 29 April to 12 June 2022, and at Romo Kultur Etxea during GETXOPHOTO 2022 until 26 June 2022.

—

Sergio Valenzuela Escobedo is an artist and curator with a PhD from the École nationale supérieure de la photographie (ENSP), Arles. After one year at the National School of the Arts (NSA), Johannesburg, he graduated in Photography in Chile and completed his Masters of Fine Arts at the Villa Arson, Nice, in 2014. He has curated exhibitions including Mapuche at the Musée de l’Homme, Paris, and Monsanto: A Photographic Investigation at the Rencontres d’Arles, which has been on tour for five years under his permanent supervision, and the forthcoming exhibition Geometric Forests at Les Rencontres d’Arles 2022. Valenzuela Escobedo is a guest tutor at international art schools and institutions, most recently at the Institut d’études supérieures des arts and Parsons, Paris, International Summer School of Photography, Latvia, and Atelier NOUA, Bodø. He is co-founder of doubledummy studio, a platform that creates a space for producing and showcasing critical reflections on documentary photography.

References:

[i] Jean Duflot, Entretiens avec Pier Paolo Pasolini (Éditions Pierre Belfond, Paris, 1970), p. 51.

[ii] Albert Camus, Homme révolté (Éditions Gallimard, Paris, 1951), p. 35.