Andy Sewell

Known and Strange Things Pass

Essay by Eugénie Shinkle

Photography is a literal medium. The idea that it might be capable of picturing the unrepresentable implies a kind of paradox. Surely a medium that’s grounded in the correspondence between light and objects can only deal in visible things? Andy Sewell’s latest body of work, Known and Strange Things Pass, suggests that photography can do more than this.

The ostensible subject of Known and Strange Things Pass is the transatlantic communications cables linking the UK and North America. But the cables are only one thread in a web of analogy that explores what it means to be in the world at the present moment. Known and Strange Things Pass is about the deep and complex entanglement of technology with contemporary life. It’s about the immediacy of touch and the commonplace miracle of action at a distance; the porosity of the boundaries that hold things apart, and the fragility of the bonds that lock them together. It’s about a reality in which everyday existence is shored up by an immense, labyrinthine instrument devised by us, but grown into something that we no longer fully understand.

In The Order of Things (1966), Michel Foucault wrote of the mesh of resemblances by which the world made itself known to the pre-Enlightenment imagination. Knowledge was organised according to systems of likeness prepared by nature itself, and revealed in the proximity of one thing to another, in affinities and analogies, in similarities and antipathies between various beings. The world was an enormous text: held together by signs and known by reading the marks on its surface.

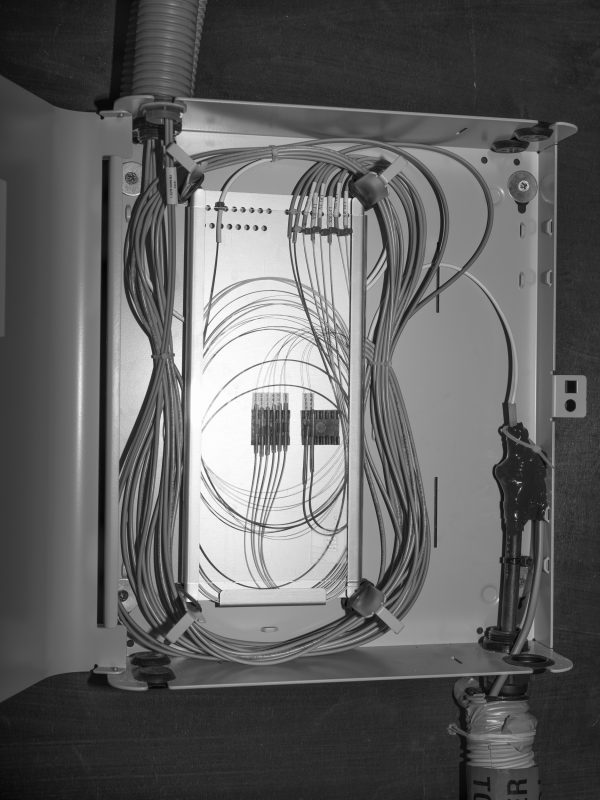

Today, the world is held together not by signs, but by slender threads of molten silica. Our lives are ordered by a vast flow of data. More than 2.5 quintillion bytes of information are created and shared every day – an unimaginable, uncountable quantity, almost all of which moves around the world through fibre optic cables running along the ocean floor. These cables make landfall in unremarkable places. They’re housed in mundane materials – concrete and metal, rubber and bitumen. Their form gives no hint of their function. There’s an ocean of incommensurability between what they are, physically, and what they represent. In Western culture, this gap between understanding and sense presentation is known as the sublime.

The photograph-as-document is a blunt instrument against this kind of complexity. Sewell understands this, and he doesn’t attempt to picture it in an image, or organise it into narrative form. Instead, Known and Strange Things Pass uses the photograph as an enigmatic and partial way of approaching the unrepresentable. The edit moves back and forth with the rhythmic push/pull of the ocean’s tides, by way of parallels and correspondences, layering and repetition and barely perceptible differences. The same magic that Foucault perceived in the pre-Enlightenment imagination is at work here too, not just in what Sewell’s photographs show – hands poised in mid-gesture, bodies immersed in the waves, cables and switches and data centres, fragile sea creatures, computer screens – but in the logic that holds them together. It’s recursive and concentric, marrying rationality and metaphor, suggesting analogies and connections without locking them down. Known and Strange Things Pass looks at the world in a way that would have appealed to Foucault, as a ‘marvellous confrontation of resemblances across space and time’.

Space and time are the raw materials of the infinite. They’re also subject to the whims of history. So when Sewell sets the elemental forms of the shoreline alongside the greyscale of control rooms and mainframe computers, he also hints at the transformation of the classical sublime into a different kind of infinity. Kant insisted that the sublime couldn’t be contained within any sensuous form, but historically, that hasn’t stopped us from linking it to the visible spectacle of mountains, skies and oceans as emblems of forces vastly more powerful than us. The digital sublime is more pervasive and more clandestine. We live with it every day, submerged in an infinite that can’t be seen. It’s not really graspable or available to experience the way that oceans or mountains or skies are. It loses its lustre when it’s grounded in everyday objects such as mobile phones or computers. And yet it’s these same objects – ubiquitous and necessary – that have become part of us and that hold our reality together.

It’s said that photography can only show the surface of things. But Known and Strange Things Pass suggests that the photograph can also grasp something of the common substance that runs beneath this surface. This, in essence, is the argument that Kaja Silverman makes in The Miracle of Analogy (2014). Photography, she writes, is more than an index or a trace: it’s a vehicle for revealing ‘the authorless and untranscendable similarities that structure Being, … and that give everything the same ontological weight’. Rather than holding us apart from the visible world, photography is a testament to the depth of our entanglement with it.

As the ocean meets the shore it exists, for a moment, in an unsettled form, a liquid mass leavened with air and transformed into foam. Known and Strange Things Pass is a meditation on the complex ecstasy bound up with this fluidity, this passage from one state to another. In a maquette for the forthcoming book, Sewell has included a quote by philosopher Timothy Morton: our reality, Morton claims, is caught up in nonhuman entities ‘incomparably more vast and powerful than we are.’ Sewell draws a more nuanced distinction between the human and the machine. Just as the rational mind can’t be uncoupled from the sensing body, technology can’t be set apart from human nature. We are indispensable cogs in this vast and powerful machine, and it, in turn, is part of what makes us human. It is as necessary to our makeup as the most basic elements from which life originally emerged, part of the primordial soup from which we all arose. ♦

All images courtesy of the artist and Robert Morat Galerie, Berlin. © Andy Sewell

—

Eugénie Shinkle is a photographer, writer, and Reader in Photography at the University of Westminster. She writes for various publications such as Foam, Aperture, Fashion Theory, American Suburb X, and The Journal of Architecture. Recent work includes Fashion Photography: the Story in 180 Pictures (Aperture/Thames & Hudson 2017) and ‘Painting, Photography, Photographs: George Shaw’s Landscapes’, in George Shaw: A Corner of a Foreign Field (Yale University Press 2018).