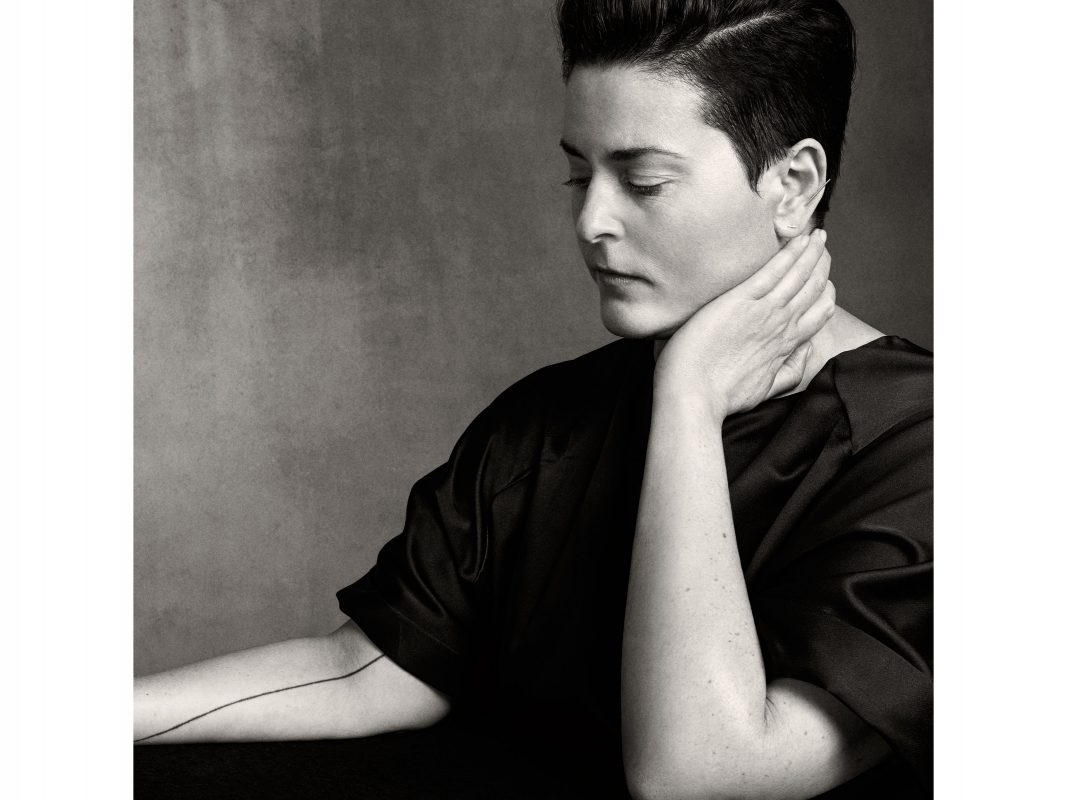

Susan Bright

Curator and Author of Feast for the Eyes: The Story of Food in Photography

Paris

For the latest instalment in our Interviews series Sabine Mirlesse catches up with curator Susan Bright in her adopted city of Paris to discusses various burning issues relating to photography and the culture that surrounds it. From the unfair dismissal of fashion photography to the trials and tribulations of a practice-based PhD in curating to reflections on the photobook craze and the under representation of women photography professionals on boards, panel discussions and juries, it’s all broached here. She also unveils her forthcoming curatorial and book projects, exclusive to 1000 Words.

Sabine Mirlesse: Let’s start at the beginning. Why did you choose photography?

Susan Bright: Initially, I didn’t choose photography, I chose art. I studied art history and then art theory and came to photography (as a career) somewhat circuitously. By the time I had finished my masters in art theory I knew I wanted to be a curator, but the fact that was going to be with photography had not settled. Through a series of encounters and some missteps I ended up volunteering at the V&A in the photographs collection. I applied as I had bought Mark Haworth Booth’s book An Independent Art and I was very taken with the way that he approached art through social history and a history of the museum. It was whilst I was interning that my commitment to photography was cemented. From that internship I got a job as Assistant Curator of Photographs at the National Portrait Gallery in London. By then I never doubted my career would be in photography. I was very lucky to learn the basics at two of the very best institutions in the UK.

SM: I think I also have to ask you the obvious question; have you ever attempted being a photographer yourself? It’s something you always wonder about curators and writers on the subject, if they ever gave it a shot from the other side initially…

SB: People outside of photography ask me this question all the time, but this is the first time in an interview and it’s rather refreshing. People outside of photography are always so incredulous that I don’t take pictures and find it somehow ‘ironic’. I smile, and ask patiently if a sports manager is also a professional athlete, an editor also a novelist or if a DJ creates their own music. Then they kind of get it, but not really. Often people outside of art and photography really don’t know what I do, but let’s be honest, most don’t really care either. If I worked for an institution it would make it all much easier, and to an outsider big names are impressive and have clout. Working with museums rather than for them tends to cause confusion.

Curators within museums often come from a more traditional art history or history route and at smaller or commercial galleries the staff have often studied photography and then realised that they did not want to be photographers but wanted to work with it somehow. So no, I have never attempted to be a photographer. I did contemplate doing ceramics for an undergraduate degree, but panicked at the last minute and thought that I should get a ‘proper’ qualification. It’s not something I have ever regretted, or indeed even thought about until now.

SM: Why do you have an affinity for fashion photography?

SB: I have always been interested in fashion photography. If I think back to the first photography I really loved as a teenager it was fashion and music photography, which of course are often intertwined. I grew up in the 1980s – how could I not be interested in music and fashion? I had a lot of postcards, records, magazines and posters. It’s just always been there as an interest. It’s not like I follow every fashion photographer religiously but I do turn to it when I am bored of art photography and it feels so refreshing and vibrant. Looking at vintage fashion work tells you so much about the time, especially about attitudes to women. I think I read them a bit more like social history documents. And of course they look fantastic on the whole and are unfairly dismissed as being superficial, which I think is nonsense. Fashion is about identity and artistry and how can that be anything but fascinating. Of course the commercial forces often dictate more than they should in how the images are formed, but you can look beyond the mainstream for work that is utterly vital and vibrant.

SM: For example?

SB: An example of this a small publication of nudes instigated by Dan Thawley who is the Editor in Chief of A Magazine Curated by. It is a riposte to a monograph by photographer Jean Clemmer published in 1969 which was daring, provocative, sexy but needless to say sexist. The clothes were Paco Rabanne’s sculptural garments and are reminiscent of a kind of sexual liberation chain mail if you can imagine such a thing. Dan asked the French designer Julien Dossena, the now head of Paco Rabanne, to ‘curate’ a series of photographs – mostly nude, but also with some of the vintage sculptural pieces. The photographer is Coco Cápitan and she revisited the original publication and shot a portfolio in the grounds of Villa Noailles (a 1920s Modernist Villa in Hyères on the French Riviera). The resulting magazine is an edition of 1000 and starts with a incredibly smart interview between Dan and Jean Clemmer about femininity, the body, the gaze, complexity of design and the sexualisation of women today. The photographs are interspersed with short poems by Cápitan in her childlike handwriting. The photographs reference and update the original book and the heritage of the Paco Rabanne brand. They are gentle black and whites done with humour, gusto, sensitivity and sensuality. The models have agency and attitude and are not just passive male fantasies. Their sexuality is very much their own and there is a freedom in a way that the 1960s sexual revolution did not really offer women a freedom at all. In a way the photographs are devoid of voyeurism (as much as is possible when photographing nudes).

SM: What is our forthcoming food photography book with the Aperture Foundation about?

SB: If any photography has been unfairly dismissed in the canonical history of photography then it is definitely that of food. My interest was first sparked when I was working on the Tate show with Val Williams and through conversations with Simon Watney. We included some Good Housekeeping cookbooks in How We Are and they said so much about 1950s and 1960s Britain – the rise of package holidays through references to Scandinavian salads and other ‘exotic’ European dishes, the desire to keep women in home after the war (the introduction is so sexist it will make you gasp), the advent of colour photography in publishing as brought to the UK by émigrés from Germany, the aspirational nature of the British middle classes (as can be even more apparent through into the 1970s with plays such as Abigail’s Party and TV like The Good Life), immigration, trade and empire through the growing popularity of curry and availability of capsicum. The photographs look so kitsch and rather disgusting to contemporary eyes. So many years later I met my editor Denise Wolff at Aperture and we find out we share a common interest in how food is photographed. We knew we had to do this book. It coincides with a glut of food photographs appearing on social networking and photo sharing sites (which again are really never about the food, but aspiration mostly), and a very concentrated interest in food politics and health. The book runs chronologically and covers many aspects of how food is photographed – cookbooks, adverts, art, packaging, fashion etc. I address how food is imaged and the complex questions about consumption, desire, pleasure, class, mortality and domesticity that arise from the act of photographing it.

SM: Aspiration for what, the same as the 1970s British middle classes as you mentioned? What would you say they aspired to for example?

SB: No, the aspiration now is very different. An Instagramed $12 ice cream is showing you can afford that and have the life style to match – it’s more about public showing off. Aspiration in 1970s Britain was more complex in a way. Young adults would have remembered the war, the rationing and their ideas of luxury were very different from what we consider today. Steak, salmon, brie would all be seen as luxury items and the idea of wasting food was totally frowned upon. Dinner parties were seen as extravagant. There is so much of British identity that was sewn into escaping this. Jonathan Coe writes about this brilliantly in novels such as The Rotter’s Club.

SM: What made you want to do a PhD? Tell me about your thesis. Tell me what you hope this new title will bring you.

SB: I knew I wanted to do a curatorial project on motherhood with the birth of my daughter. I figured that if I was going to spend years researching it then it would be good to have some institutional support and a structure in which to frame the research as the subject is so vast. I also wanted to rethink my relationship to curating which had been on rather a frenetic path. I wanted to take a breath to think through the changes in photography and my relationship to it too. The PhD process certainly allowed me to do all of those things. By giving me the opportunity to read widely around new developments in photography and how that affects curating I have come back to curating so much more informed. To have the time to step out and reconsider was a luxury in many ways.

So my PhD is practice-based in curating, which means I write a thesis and present my practice, (which is the exhibition Home Truths). In the thesis I investigate contemporary ‘maternal ambivalence’, which I define as stemming from a reaction to social norms, expectations and the cultural conditions. I use the literary frame of ‘life narrative’ to examine maternal ambivalence in the artworks I curated, contextualising these within depictions of mothering in the larger photographic culture of motherhood.

SM: Could you elaborate on some of these depictions?

SB: These depictions were directly dealt with in a digital display I curated with Katrina Sluis titled Motherlode, which was shown at The Photographers’ Gallery at the same time as Home Truths. These include tropes that easily categorised into generic lists of activities including: the sexy nude pregnant portrait, the post-birth snap-back-into-shape transformation, cute outings with children, loving husbands (and a lack of nannies), and going back to work within weeks – the latter putting huge moral pressure on the idea that mothering itself is not a socially or economically significant activity.

At the heart of all my research lies an investigation into different maternal life narratives (in literature and social networking and art photography) and how exhibitions have to respond to autobiographical approaches in photography as we increasingly experience them on the web. As to what the new title will bring me I don’t know. Very little probably.

SM: Very little because a PhD in art is not appreciated or valued in some way?

SB: No, it is valued and appreciated but it will not change my job nor will it change my pay scale or make any other tangible difference. The title is just that and I do not really care for titles. The process of doing it has been vital to me and I believe it has made me a better writer and researcher and prepared me with tools to explore deeper into issues that I perhaps would not have done so before.

SM: What do you think about the photobook craze?

SB: I come to the photobook from the receiving end rather than the making end. So on one hand I can see it’s a great way for photographers and artists to see their work realised, allowing them to be able to do this easily and exactly how they like it though self-publishing. The flip side to that ease is there are an awful lot of not very good books out there. To make a book it has to make sense of the work… I don’t feel it always does. Also with self-publishing numbers are small, and the collectors smaller so I would question if artists are really ‘getting their work out there’. If they want their work to be seen, then obviously the web is the best place for that.

I attend events like Offprint and the New York Art Book Fair and I feel like I am in a totally alien environment. I tend to go with friends who collect and I realise I don’t share their passion. They are fascinating to me… their knowledge and hunger is obsessional. It’s like being with people who are obsessed with vinyl or even stamps, it just happens to be photobooks, but more than that it’s about collecting – having the latest, having them all. And when I am at events like Off Print and NYABF I ask myself where are the women? They are not starting up small publishing houses, they are not buying in the same way men do and they are not represented in the books in the same way. There is absolutely no reason for this, if ever there should be a field that is not gender biased then it’s the making of photobooks, but that just doesn’t seem to be the case. I only buy what I really love (and one artist for investment) and recently got rid of 7 huge boxes of books. It felt wonderful. Having so many photobooks got really oppressive – I am really selective now. It has to be pretty special to make the cut.

SM: What happened to the seven huge boxes of books? I often wonder about where all the mediocre limited edition self published books end up…

SB: Those seven boxes of books went to the Library at the Paris College of Art. I think students will benefit from them a great deal more than I will.

SM: You are also a teacher. Can you tell me what you think has changed in terms of how photography is being taught at higher education levels? What’s your take on the whole MFA trend – is it just a cool club that leaves you in loads of debt or something you’d recommend for a young artist wanting to move forward?

SB: I teach very little nowadays – just one class a semester that I team-teach at Paris College of Art. I started teaching about ten years ago and very little has changed. To be honest it often leaves me very disillusioned and I think the whole state/public tertiary education system is a mess and one that is under huge commercial pressures that do not always serve students well. Classes are getting bigger and the prices are getting higher. I have reached a point now where I think that alternative workshops and events and private colleges might give photographers a better education in some ways. I am a huge advocate for state education and it saddens me to say this. Having said that I do think MFAs can be incredible. For a photographer to do one it shows they are serious about what they are doing and can certainly give them access to not only equipment but also different voices that may challenge them to think about photography differently and their practice more specifically. It also introduces them to their peers – this is something that I don’t think students realise is incredibly valuable. The money situation is certainly an issue – a big one – but overall I would recommend a MFA for a young artist wanting to move forward. Where that is done, how it is done (part time, full time or intensive) should be meticulously researched so that it’s absolutely the right decision.

SM: What are your reflections on being an independent curator rather than being attached to one institution? What are some of the pros and cons of being free as a bird? I know you’ve been approached regularly for fancy positions, if I’m allowed to keep it vague but mention it just the same. You turn them down each time?

SB: I think the ‘proper job’ is something that plays on all independents’ minds. It goes with the territory. Being independent is not a secure position, you either rise to it or you don’t. You are either suited to it or not. What comes along with it are existential crashes of confidence, panic about what you ‘should’ be doing, comparisons with those in institutions, and other such human moments. These feelings are part and parcel of the lives of those who are not attached to a job (and perhaps also those who have a regular job too). But what I know is these feelings are same for writers, actors, and artists, everyone who has chosen a slightly different route. And to make matters worse they are all are exacerbated with age. The advantages of working independently are endless as I see them – these include flexibility, lack of boring meetings, more freedom to work on projects of your own doing, a faster turn around etc. Cons include: lack of support, nice colleagues, and of course the regular pay cheque. In some ways the grass is always greener though. As you mentioned I have been approached for some quite prestigious positions. My ego goes crazy until I read the job spec and I think ‘I don’t want to do that’. It’s always such a surprise as I guess I still think that is what I want to do, or what I should be doing, or what I have been working towards. The life I have been able to make for myself always seems more appealing when it comes down to it. So I will keep working independently until a job or my life situation needs or wants it. When I read a job that comes up favourably I will go for it. I honestly don’t know what that would be or where, but I always keep an open mind to it. I have just moved to France and have the language barrier to consider, so in a way I have perhaps unconsciously (or perhaps it was consciously) made a situation for myself where I have to carry on doing what I do. Life comes in phases – now I am closing my PhD I feel like my life is taking off a bit again after five years of knuckling down and researching and writing. I feel like I can take more on now, travel more and think more widely about where my career might lead, what is important to me, and also the possibilities of photography. It feels fantastic!

SM: Can you unleash your thoughts on the representation or lack thereof of women photography professionals on boards, panel discussions and juries? You boycotted Photo London 2016 for this reason I remember so I believe you have some strong opinions about it (rightly so!)

SB: I think with these things you always have to look at numbers. It’s a simple matter of counting and then you can see the disparity easily. With Photo London I counted up the female/male ratio and it did not look good. I have just looked at the archive. It proudly says there are over 50 events – on the archive there are seven women. This does not include panels. There is a panel on journalism in a Digital Age (five on the panel – one woman). And there is a panel on women photographers (titled Loose Women!) If there was a better spread of women on the overall programming there would be no need for a separate panel. You don’t want to get me started on the representation of anyone of colour! There may have been more women in the full programme – but I am sure it was not one that showed an even spread. It’s SO EASY to prevent this. I makes me tired that I still have to say this. We all have a responsibility regardless of our gender to make sure there is an even and fair spread of all people, all types of photography and all ages, race, sexuality etc represented in a big event like this.

But you see it over and over. I have lost count of the amount of panels I have been on where I am the token woman. People wonder why women drop out of photography – but if you can’t see it you can’t be it. How are young female students supposed to feel inspired by female mentors, photographers, etc when they are simply not visible? Also look at agencies like Magnum – how many women are there in their 40s and 50s in comparison with the men? Again, I am just looking at numbers. Go back twenty years of the Deutsche Börse Photography Prize and count. The thing is when I teach there are predominantly young women in the class, so what happens between then and being awarded or nominated for prestigious prizes such as the Deutsche Börse? That prize is nominated by shows and books – for me the simple answer is to be sure that women are given shows and publishing opportunities so that they can then be more likely to be nominated. It’s a constant effort all of the time for everyone. I think as we are entering a period of revised misogyny, homophobia and racism in the culture at large it’s especially important to stress this. With juries I have to say it’s a different story, I have found them always to have a better spread.

SM: I recently was discussing with someone how often the role of the gallerist or the photo editor is a woman and the photographer/artist is a man. Do you agree? Why do you think that is?

SB: I read an interesting interview with Max Houghton recently who said, “We have a set up a wonderful service industry around male artists; there are lots of models that show this: the gallery, the magazine, the museum.” I have been mulling this over ever since I read it. It also goes back to teaching and all those young women who by the end of their degree have no desire to be a photographer but want to work within photography. I am not sure I would go so far as to say we have a service industry but there are certainly a lot of women working within museums, magazines and galleries, but there are also men. Looking at some of the new high-profile appointments in museums they all went to men. I would certainly say in the UK and US the majority of assistant curators and curatorial assistants are women in the major institutions. It then begs the question why all these women are not more invited onto panels. But honestly, I don’t know why there are not more female photographers and artists in the mix. Again it goes back to making sure they are not working in vain and are getting the exposure and fair representation through publishing and exhibitions and in the market (by which I mean the auction houses– rather than commercial galleries. The former is still very much pushing and promoting the dead white American male, which are the big sellers).

SM: Let’s talk about being sick of photography and what you turn to for inspiration when that happens?

SB: I don’t really get sick of photography – but I do get sick of the culture around it. The same names writing in the magazines, the same artists getting shows and being represented by commercial galleries. It makes me feel claustrophobic and the whole thing can feel village-like. When this reaches fever pitch I tune out and turn to literature – always. Fiction mostly, but also social histories and memoir feature heavily on my reading lists. I also read a huge amount of children’s stories. But then something shifts and I am into it again. I have to say this usually comes from something fictional I have read that leads me back to thinking about the medium in a different way. Or I just go to a wonderful show and get excited by the possibility of an exhibition – the curated space is totally inspiring to me. I have taken to going to shows at night so they feel more like theatre, this simple shift in time and atmosphere really makes a difference and adds a drama that is missing in daylight.

SM: How about this exhibition on death you are preparing? Can you tell me about it?

SB: I am co-curating this with the artist and scholar Ruth Rosengarten. We joined forces as the topic represents the area where our research interests intersect and overlap: mine in the autobiographic turn in photography, Ruth’s in family archives and the blogs and photobooks that track the trajectory of an illness. We have noticed how over the past few decades, photographic images have proliferated (whether in exhibitions, photobooks or online on blogs, image-sharing sites or social media) focusing on the aged and the terminally ill. This coincides with two interrelated factors: on the one hand, a cultural turn towards the autobiographic, finding expression in texts, films and the expanded field of self-portrait photography; on the other hand, the spread of what has come to be termed the “grief memoir” and of the idea of working through feelings of loss.

Despite the creative freedom granted by digital imaging many artists continue to use photography as a means of holding onto evanescent time and encapsulating moments as they evaporate. This, of course, is key to much theoretical thinking around photography and death where death is ensnared in the history of photography itself, in particular in the wake of Camera Lucida.

SM: One of my favourite passages on the notion was part of an essay written by Eduardo Cadava in the collected writings on Camera Lucida edited by Geoffrey Batchen, Photography Degree Zero. I like it so much I have it tacked to my website. It’s about photography condensing the relation between the dead and the living. I think one of the reasons it appeals to me as well is because it explains in a nutshell the spiritual aspect of photography. Yes I said spiritual. Yes you just cringed I think.

SB: Well I think that idea works up to a point and certainly with photographs that document an event, but the counter-idea of the photographic image as a construct or invention has also had a place in the ever-growing genre of photographs of the aged and dying. When a photograph is made or staged I am not sure that idea translates to the more expanded ideas around photography.

The constructed image, since the very inception of photography in the 19th century, and shadowing empirical, documentary image-capture like an uncanny doppelganger, has existed photography that avows its own inherent artifice, its status as fabricated object. This can be seen in the one of the first photographs ever made (Hippolyte Bayard, Portrait as a Drowned Man, 1847) and the composite Fading Away (1858) by Henry Peach Robinson.

SM: That is to say, people who photograph a fictional death?

SB: Those two examples do but that is not what we are interested in. We have decided to make our starting point for this investigation into a counter history to the subject in the late 1960s and 70s and deal with both ageing and dying. This period saw an increase in documentary styles of photographing the dying, but we wish to step away from the indexical and consider the more metaphorical role of photography – one that relies on fabrication, invention and construct. Artists that fit into this idea include: Helen Chadwick, Jo Spence, Duane Michals, Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Stéphanie Beaudoin and Tatsumi Orimoto, for example.

SM: What are some of the first elements you consider when you began the making of an exhibition in general? Can you walk us through your thought process a little?

SB: Every exhibition is different. It can start with an idea or a feeling, which I then drill down to something tighter or it can start with an artwork that I think resonates with another and a theme emerges. I must say I work pretty intuitively and often what I am trying to say comes clearer to me as the project evolves – I guess that is a pretty common creative process. I tend to work very closely with artists – this process reflects the idea of ‘conversation as creative practice’, whereby many private thoughts become public through the act of curation. It’s very much a joint effort. But a lot of curating is hard admin and this needs to be made clear as I think many people are not fully aware of this and think its rather glamorous. There are endless checks on prints, sizes, transport, plans, etc. It’s the beginning and end of the process that feel more fluid and creative. I learn something about the work from every installation. It’s always a wonderful surprise to see something I so clearly have in my head manifest into physical space. It’s like magic.

More recently I am thinking more about what the exhibition space offers and how to make the most of this space – not just in terms of installation but what a physical space can offer an audience that is different from experiencing work on a screen. This can be seen in the long-term discussions I have been having with an artist who is due for a mid-career. But I am not sure what audiences really gain from mid-career retrospectives apart from drawing the threads together. I don’t think that is enough. So we are working on something much more expansive, looking at her influences, obsessions and daily life and how to add those into the mix to give the audience a much clearer idea of what is in the work but not necessarily obvious from looking just at the photographs. It can go any way and can bring in all her artwork that is across other mediums. I want it to feel like a real experience to visit: confronting, surprising and honest in that influences and inspirations can be out in the open. I foresee there may be events and performances too. It’s challenging for both of us, and we are not quite sure how it will pan out, or what kind of venue will be right, but we hope to create something that will hopefully make an audience look at her work anew and open up the possibilities of how we can bring in autobiography into an exhibition in a physical space.

SM: You left New York City for Paris a year ago, a big change! Can you tell me a little about the trajectory of your geography over the years – why you left the UK and then why the move to Paris? Any plans to move back to England? Can you tell me about what the differences between the photo scenes in New York versus Paris versus London are in your experience?

SB: Paris doesn’t really feel like a change in many ways as I am European and am very comfortable with many of the sensibilities – much more so than I ever was in the US. In other ways it’s a huge change, but I think these changes are more personal. As mentioned I am coming to a certain phase of my life with my PhD finishing so that is a big change and my family situation is different. In a good way – Paris marks a change for how we operate as a team and it’s so much more satisfactory for everyone.

I left the UK in 2007, I had had a big year curating Face of Fashion at the National Portrait Gallery and co-curating How We Are at Tate with Val Williams alongside a smaller exhibition about sculpture, abstraction and photography in Oslo. There was a bit of a feeling of what now? I was also pregnant. So what happened was my husband got a job in New York so we decided to go for it. I had always wanted to live there so it seemed like the perfect opportunity to go. We ended up living there for nearly eight years. I never imagined it would be that long. We moved to Paris for many reasons – most of them personal. I really missed Europe and wanted to be ‘home’. Home is Europe, not the UK.

SM: I think you have a better quality of life in Paris than in New York. A number of friends in New York have since left for other cities as well. New York isn’t the affordable place our Baby Boomer parents got to enjoy and make art in anymore. As for photography – I think the US feels a bit more commercial if I’m allowed to sweep it all into one which is pretty unreasonable. There is more community feeling in photography in Paris as well – you see the same people at the same fairs and festivals, it becomes your network and to some degree social circle. In France they are much more romantic about photography, to a fault.

My own observations living in Paris the last five years have led me to become aware of a heightened sense of nostalgia that the French hold for traditional photography – everything from Capa to Cartier Bresson to William Klein. Have you observed that as well? If so what do you think of it? Do you see it as an obstacle or a form of enrichment?

SB: Yes, I think that is a fair observation. Living in different countries you see patterns of how photographic history is played out publicly. These points are generalisations, but in the US I feel there is a hero worship of certain photographers – Walker Evans, Robert Frank, William Eggleston, for example – and this is similar to the way the French revere their heroes. And I think it’s fair to say that Europeans know a lot more about American photography than Americans know about European photography (let alone photography from other parts of the world). I have also found the French still have a great deal of respect for photojournalism even in the gallery world – this is not a sentiment that is generally shared in Britain at all. I think Britain could benefit from promoting and respecting their own – they are still somewhat in thrall of American photography to a degree. But the French sense of nostalgia is an interesting and complex one, which is tied very closely to issues of national identity. I know this sounds woolly, but I think its both an obstacle and a form of enrichment – it all hinges on how it’s curated, what contemporary work its working with (or against). I don’t think it’s enough just to show this kind of work without some kind of curatorial framing or investigation into why its being shown now and what it means to represent the work now. It’s this reframing that I find is sometimes lacking in France.

SM: Do you think there are just too many photographers these days?

SB: No, I think the history of photography is littered with disaster metaphors of abundance, although usually directed at photographs rather than photographers. Think of narratives such as bombardment, floods, feeling overwhelmed etc. Just because anyone with a smart phone takes photographs (and often calls themselves a photographer) it doesn’t mean they are one. If that were the case we would all be writers too – we all write (shopping lists, emails, texts etc) but nobody would say there are too many writers.

SM: If you couldn’t be involved in photography, what other profession would you attempt?

SB: I really, really wanted to be a Blue Peter presenter. But having done a little bit of television I know this would have been a disaster as I am not good on TV. So hopefully I would have discovered this early on and worked in radio which I absolutely love. I think it’s very important medium. The rise of podcasts gives me such pleasure. I have been chatting with a friend about us doing a series about photography – when things settle a bit we will put our minds to it properly.

SM: I had to just quickly google what Blue Peter is, not being British, and it says it oldest television programme for children. I’m sensing a theme here. Am I allowed to mention that one of the first times we hung out you went home and wrote a children’s story about a fictional me? Is it just the endless fantasy of children’s narratives that appeals to you, for almost the same reason that fashion photography does?

SB: I did indeed write a children’s story inspired by you. It has become the first in a trilogy. They are all about two characters who have rich friendships. I think I am immensely interested in the concept of fantasy – exacerbated by living in Paris which I do believe has a collective one. The tourists that come here are also living a fantasy out. One based on art and literature and architecture which has very little to do with the realities of the city. I’ve been working on a commission with Alessandra Sanguinetti for the Aperture Foundation and The Fondation d’entreprise Hermès. She has managed to see this and capture it perfectly of course. This collective fantasy is also something I see in your work.

SM: I think I’m supposed to comment yes or no, enthusiastically. I have to ask you what you mean more precisely by collective fantasy though. Do you mean magical realism?

SB: No, I mean more along the lines of ‘invented tradition’, which was coined by Erik Hobsbawm in 1983. The authors in the edited book of the same name argue that traditions, which seem to be essential to a nation or attitudes of nationhood are often relatively new and invented. These seem to legitimise cultural practices and are often based in fantasy. I think your personal work in Iceland and Armenia does this – and also considers the role of myth in national identities. I think Alessandra’s work has elements of magic realism and she has wonderfully managed to capture that spirit in her work in France too.

SM: In that case I will nod enthusiastically and add that I look forward to seeing Alessandra’s new work and that I feel flattered to be mentioned in the same breath. She was my very first interview while I was still in graduate school. You are my twenty-fourth, which I can hardly believe. Speaking of school, that leads me to another question. What is a common mistake you see emerging photographers making as they start to make their way?

SB: I think its often a case of wanting too much too soon when the work is not strong enough or fully developed. Getting work out there before it’s ready does young artists no favours. And more generally there are other ways to conduct yourself that are important. Firstly, I would say when you have a meeting with somebody make sure you are prepared and have good work to show. You can easily meet somebody once, twice is harder, so don’t blow it. Don’t be drunk, stoned and have a bath. I have encountered all these scenarios and it’s not very impressive (although quite memorable!)

Also when you email people you don’t know don’t ask for feedback just send an email highlighting the new work. Curators, editors and other people who work in photography receive a lot of emails from people they have never met asking for feedback. On the whole everyone I know looks at work if they are sent an email, but they do not have time to respond and feedback to everyone, so do not get defensive and angry when you do not get feedback – that is really unimpressive. I am finding I am getting more and more newsletters now and I am unsubscribing. This used to be a good way to communicate, but I am not so sure now. The overload can be too much. But really it’s often-basic common sense – be nice, have good work, listen and keep in touch but not oppressively so. ♦

Image courtesy of Susan Bright. © Sabine Mirlesse