Acts of Resistance

Photography, Feminism and the Art of Protest

Exhibition review by Max Houghton

Acts of Resistance, a collaborative exhibition by the South London Gallery and V&A Parasol Foundation for Women in Photography, confronts the systemic brutalisation and circumscription of women’s bodies worldwide — from persecution in Bangladesh, oppression in India to solidarity with Palestinian freedom. As Max Houghton writes, this is not a show for performative activists; it’s really doing the work — the exhibition fosters a reparative gaze, challenging historical narratives of control and subjugation, and calling for greater community involvement and institutional accountability.

Max Houghton | Exhibition review | 4 Apr 2024

Even before entering Acts of Resistance: Photography, Feminism and the Art of Protest, a curatorial collaboration between South London Gallery and V&A Parasol Foundation for Women in Photography, the content guidance reveals the show’s necessity: ‘Artwork in this exhibition includes references to […] sexual violence, femicide, female genital mutilation, gender and sexuality-based discrimination, genocide and racism.’ This short institutional statement tells us precisely how the world is structured and how the bodies of women+ are circumscribed and brutalised, deliberately and systematically. Stepping in, the first visible work, suspended from the ceiling, takes gentle possession of the viewer, who is immediately enfolded into the plaited hair of young Iranian women. Three larger-than-life prints by Hoda Afshar are responding to Iran’s Women Life Freedom movement with the symbolism of unveiled hair, of the plait’s own revolutionary turn, or pichesh-e-moo, and of the dove’s flight between peace and martyrdom. The death of Mahasa Amini at the hands of Iran’s morality police weighs heavily, as does the courage of the women who protest, risking their own lives. My thoughts turn too to the immorality and illegality of the Metropolitan Police on this city’s streets; to the lives and legacies of Nicole Smallman and Bibaa Henry, of Sarah Everard, of Chris Kaba; and to what kind of imaging or imagining might bring justice to them.

The first message, then, of the show’s images is that they open a space within which such global ultraviolence can be considered, resisted and perhaps – rarely – extinguished. Two artists whose works are curated close by, Poulomi Basu and Sofia Karim, are committed activists, whose work has given rise to legal change. Basu’s multimedia work and its dissemination contributed to the banning of Chapaudi in Nepal, a practice which sees girls and women banished from society during menstruation; left to inhabit unlit, unsanitary temporary huts, at risk of assault in remote fields.

Karim’s activism was ignited by the political imprisonment and subsequent torture of her uncle, the renowned photojournalist Shahidul Alam, in Bangladesh. Like human rights activist G. N. Saibaba, for whom she has also campaigned through her exquisite drawings and letter exchange, Alam was eventually released. Karim’s work, Turbine Bagh (2020–ongoing), resonates in any setting, though in a night at the museum, it would surely leap off its designated shelf and populate a central artery through the space. Significantly, it is the only work in the show that foregrounds the art of other activists, which Karim has transferred onto samosa packets, conferring an increased sense of sociality and hospitality within these acts of resistance. For this show, whilst works centring women’s experience have been selected, in terms of anti-rape protests in Bangladesh or Muslim girls’ right to wear a hijab in Karnataka, India, Karim’s feminism also insists upon exposing the cruelties of the caste system via a Dalit protest in Una, and the Kerala Sisterhood’s support for Palestinian freedom. From her series Sisters of the Moon (2022), Basu’s futuristic self-portraits pool, siren-like, across the gallery walls, seducing the viewer into uncertain territory, incanting through their worldly knowledge the names of pain. The spectral image of Basu on a bed, uncannily placed at the shore’s edge, alongside water urns, invites questions of refuge, of sanctuary, of survival, and helped raise £5million for WaterAid.

This is not a show for performative activists; it’s really doing the work. Three major London institutions have curated feminist/activist shows in the past year; a welcome and vital taking up of art space by, for and with women+. This outpouring of activist-propelled art, in terms, for example, of the vast scale of Re/Sisters (2023) at the Barbican and Tate’s Women in Revolt! (2024), or the geographical breadth of Acts of Resistance, is indicative of the fact that such shows are long overdue, and we have so much to say. I say this in the year the Royal Academy offered its first ever solo show to a female artist, Marina Abramovic, in its 250-year history.[i]

This show has taken the idea of the “fourth wave” feminism of the last decade as its timeframe, which is at once necessary to fit the available space, ensures intersectional and expansive feminisms – a plurality noted in the show’s subtitle – and yet misses the chance to visually connect these present concerns through time. Such legacies are not, however, absent. The show’s first section, “Body as Battleground”, is essentially a dedication to Barbara Kruger, whose own solo show at the Serpentine took place earlier this year. The legacy of the Saint of Christopher Street gay liberation campaigner and trans activist Marsha P. Johnson is enshrined in Happy Birthday Marsha! (2018) by Tourmaline and Sasha Wortzel, which reimagines the night of the 1969 Stonewall uprising, when, yet again, the role of the police as guardians of the most vulnerable is found entirely wanting. The way Johnson inhabited her personal freedom was revolutionary; achingly beautifully rendered in this short film, in what Saidiya Hartman might call a ‘critical fabulation’, in which historical or archival omissions of a life are reconstructed. This work occupies the emotional heart of the show, along with that of Aida Silvestri’s Unsterile Clinic (2015). By any measure, this is an astonishingly visceral work, on a subject no one but no one wants to talk about, yet is transformed by the artist’s loving hands into artworks of such grace, they turn silence into speech. Drawing on her own experience of female genital mutilation, she has been able to work collaboratively with other similarly-affected women to visualise the different forms the procedure has taken, creating models, on display here in a vitrine, which are now used for identification – over 200 million women and girls are affected globally – by the NHS in the UK. The work also takes the form of a single, non-identifying self-portrait, in which the artist wears a wedding dress, embellished with razor blades in place of pearls, and embroidered red thread, flowing beyond the frame. The image pulsates with the injustice of the religious and social construct of virginity and every act of violence it has engendered.

I unite these two specific works in the strongest spirit of the right to self-determination – and its frequent absence – which courses throughout the exhibition. Of the two vital works on the subject of abortion, in this instance, I would have selected Winant’s The Last Safe Abortion (2023) for the light it sheds on the recent overturning of Roe v. Wade in the US, and invited Laia Abril to show her work On Rape (2020–ongoing), or Femicides (2019–ongoing), as another bloody framing for the show as a whole. Yet, as always with her meticulously researched work, Abril’s situating of abortion as a global institutional failure bristles with eloquent rage. The last time I wrote about Nan Goldin’s Memory Lost, the V&A was still funded by Sackler, a position it reversed in 2022; the result of a sustained campaign by Goldin and PAIN, which included a die-in at the museum, indicting the creators of Oxycontin, the highly addictive opioid, for their life-destroying crimes. Goldin’s way of being in the (art) world – she has been called a “harm reductionist”, surely an aspirational epithet – is propelled by honesty, and, I can’t say it too often, by love. The wrong things, she says, are kept secret. They still are, and the shame that encircles such secrecy kills with the same violence as a blade or a gun.

Much of the work in this ground-breaking show pierces such shame with love, and Raphaela Rosella’s work HOMEtruths (2022) explodes with love and care for and with a First Nations community in New South Wales, Australia. This entirely unsentimental, joyful, heart-breaking, polyvocal three-screen film shows the effects of the incarceration of women on them and their families. Part of a wider work, You’ll Know It When You Feel It (2012–ongoing), Rosella’s co-creational approach resists, intervenes in and often completely overturns juridical and bureaucratic representation and replaces it with rich familial bonds in a form of justice, both aesthetic and restorative, which is exceptionally deeply felt.

In terms of the photographic image, these artists are pushing the discipline forward, far from its histories of control and subjugation. In their hands, we encounter sculptural, filmic, archival, collaged and embroidered forms, which make for multi-sensory ways of seeing, decentring the camera’s power; a reparative gaze. Questions for the next shows foregrounding women+, no doubt already in production, include how to understand the gallery as even more of a forum, involving more community groups and building on existing links with brilliant but underfunded and therefore precarious local resources. How can the institutions that fail us, that maim, that kill, be further held publicly accountable via image-led or art-based discussion? How can artists whose practice isn’t defined within the confines of socially engaged practice in and of itself expand the social purpose of their work in a gallery space? And how can the white Western female curatorial approach, expansive and assiduous as it surely is, in terms of Sarah Allen and Fiona Rogers, as well as Alona Pardo and Linsey Young – brava to all – continue to find ways to share its considerable power ever more effectively? Not because it isn’t showing us the most pertinent, mind-expanding, courageous work, not because it isn’t taking great care of the people who make it, but because of what it – and I – just can’t see.♦

All images courtesy South London Gallery

Acts of Resistance: Photography, Feminism and the Art of Protest, with a public programme curated by Lola Olufemi, runs at South London Gallery until 9 June 2024.

—

Max Houghton is a writer, curator and editor working with the photographic image as it intersects with politics and law. She runs the MA in Photojournalism and Documentary Photography at London College of Communication, University of the Arts London, where she is also co-founder of the research hub Visible Justice. Her writing appears in publications by The Photographers’ Gallery and Barbican Centre, as well press such as Granta, The Eyes, Foam, 1000 Words, British Journal of Photography and Photoworks. She is co-author, with Fiona Rogers, of Firecrackers: Female Photographers Now (Thames and Hudson, 2017) and her latest monograph essay appears in Mary Ellen Mark: Ward 81 Voices (Steidl, 2023). She is undertaking doctoral research into the image and law at University College London and is the 2023 recipient of the Royal Photographic Society award for education.

References:

[i] I say this in a year when the police force with responsibility for London remains institutionally sexist, racist and homophobic. I say this when two women this week, as every week, will be killed in the UK by the hands of their partner or former partner. I say this on a day when the US abstained from the UN vote for a ceasefire in Gaza, where sexual violence is being frequently reported as a weapon of war.

Images:

1-Hoda Afshar, Untitled #14 from the series In Turn, 2023. © Hoda Afshar. Image courtesy the artist and Milani Gallery, Meeanjin / Brisbane.

2-Sethembile Msezane, Chapungu – The Day Rhodes Fell, 2015. Photo: Courtesy the artist

3-Tourmaline and Sasha Wortzel, Happy Birthday Marsha!, 2018. Courtesy the artists and Chapter NY, New York.

4-Poulomi Basu, from the series Sisters of the Moon, 2022. Courtesy the artist, TJ Boulting and JAPC.

5-Guerrilla Girls, History of Wealth & Power, 2016. © Guerrilla Girls, courtesy guerrillagirls.com

6-Mari Katayama, just one of those things #002, 2021. © Mari Katayama

7-Zanele Muholi, Bester, New York, 2019. © Zanele Muholi. Courtesy Yancey Richardson, New York.

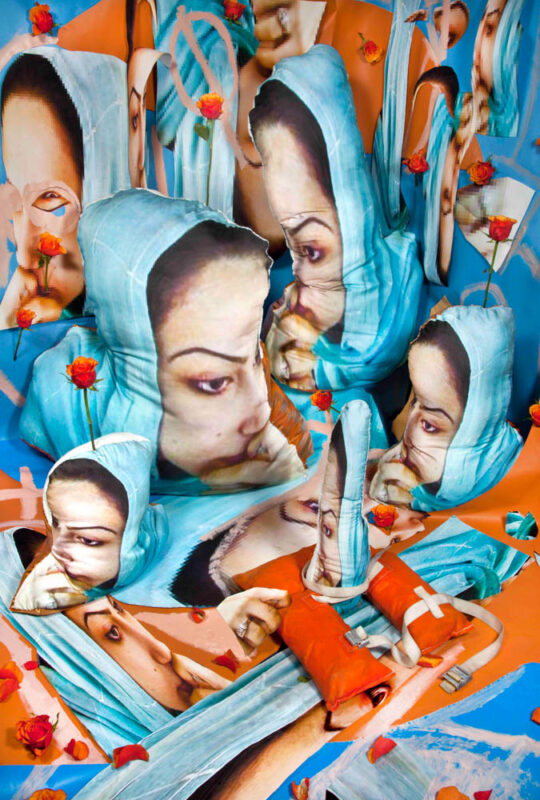

8-Sheida Soleimani, Delara, 2015. © Sheida Soleimani. Courtesy Edel Assanti.