Lesley A. Martin

Publisher at Aperture Foundation

New York

In the latest instalment of our Interviews series, Jeffrey Ladd speaks with the publisher of Aperture Foundation’s book programme, Lesley A. Martin. Their conversation reflects on the current state of photobook publishing, the idea of misperceiving books as the most viable vehicles to launch careers, as well as her thoughts on the seldom-discussed phenomenon of publishers taking on projects by photographers who pay a premium of the entire book production.

Jeffrey Ladd: How long have you personally been interested in photography and photobooks?

Lesley A. Martin: My interest in photography is probably fairly typical – an early introduction to the magic of the darkroom by a family member, hanging out with photo geeks in high school. I knew I was interested in it enough to pick it up as a minor in college. But the realisation that photographs had power and could become vital to a public conversation comes from having lived an hour away from Cincinnati, Ohio at the time of the Robert Mapplethorpe Perfect Moment exhibition at the Contemporary Arts Center, and realizing that the culture wars of the 1980s and 90s were perfectly and terribly crystallised in this battle over which images would be considered true, beautiful, and permissible.

I don’t have a story about a particular book that changed my life as my interest in photobooks came somewhat obliquely – yes, I was always the kid with glasses that “loved books”. Yes, I worked my way through college at the Art and Architecture library and decorated my dorm walls with jackets of books that had been discarded before they were allowed to be shelved. And yes, I lived in Japan and spent a lot of time looking – sadly, not buying – books by and about Japanese photographers, but it wasn’t until I did an internship at Aperture that it dawned on me that there were people behind the making of those books… and that this was something that I could do, too.

JL: How long have you been at Aperture?

LAM: The best way to put it is that I’ve been at Aperture for roughly sixteen of the last twenty-one years, but not continuously. It’s a little scary to think about.

JL: How have your thoughts on photobooks changed over the course of your involvement with Aperture?

LAM: The ecosystem as a whole has changed pretty radically over the last twenty years. There were a particular set of formulas that Michael Hoffman, longtime publisher and director of Aperture, believed in. I’m really not sure what he would have made of the photobook world now. I left Aperture for a few years in 2000 when we began to disagree over the type of books that could – and should – be published. I sometimes use Eikoh Hosoe’s Kamaitachi as an example of just how much things have changed. Michael loved the 1971 edition of the book with its baroque use of gatefolds and wanted very much to find a means of reissuing it as a facsimile. The costs were daunting, and in 1997, when we first started discussing it, the idea of printing the book in a very small number and charging a higher price was not part of the Aperture model – he felt there wasn’t enough of a collector’s market to make that work. Now, of course, that’s a model most publishers incorporate into their arsenal of publishing strategies. When I returned to work at Aperture in late 2003, one of the first things I did was to put in motion a facsimile of the book. We commissioned a new slipcase by Tadanori Yokoo, and released it in an edition of 500 English-language copies and, working together with a Japanese publisher, 500 Japanese-language copies. The book sold out almost immediately. It had become evident by then that not only was there an audience but that this audience of collectors and dealers were building a new body of scholarship and connoisseurship of the photobook. This knowledge base, coupled with the shift in how accessible printing technologies have become and how much creativity is coming out of the self-published and independently published worlds, have increased the interest and appreciation of the book form. The idea of strict, old school publishing formulas of any kind, has been turned on its head, which is good for everyone.

JL: How do you think your direction as editor has been different from others? (past Aperture editors? Or other publishers?)

LAM: As a not-for-profit organisation, Aperture needs to be willing and able to explore a fairly broad interpretation of photography – but of course, it’s also an amalgam of individual tastes and interests. Over the course of almost sixty-five years, there have been so many book editors, each of whom left one imprint or another – from Nancy Newhall, one of the founders, onward. (Keeping in mind, too, that the book editors and the magazine editors used to be one and the same – now the book and magazine programs operate synergistically but autonomously). There are lots of odd little pockets in the Aperture backlist –Newhall worked closely with Edward Weston and Ansel Adams. She was focused on the interchange of text and images and on the struggle for the recognition of photography as a ‘fine art’. Mark Holborn introduced Japanese photographers like Eikoh Hosoe and Shomei Tomatsu to Aperture, alongside British photographers like Bill Brandt. Carole Kismaric made a critical contribution, bringing in Robert Adams, Stephen Shore, John Gossage, and moved Aperture’s book program away from a certain beaten path – more ‘windows’ than ‘mirrors’. Michael Hoffman’s obsession with India can be read in vein of books by Raghu Rai, Raghubir Singh, Mitch Epstein’s first book: In Pursuit of India, while also championing the publication of the Arbus monograph.

Current senior editor, Denise Wolf, has introduced a line of books about photography for children. Aside from my interest in Japanese and Dutch photography, which happen to be great photobook making cultures, I feel that my task over the past decade has been to ensure that the book programme felt relevant overall. I didn’t want Aperture to just do one kind of book, but to be able to publish across a range of types of book – to be more varied, flexible, and contemporary in our book making. I also made it a goal to engage with and help support the growing conversation about the photobook.

JL: Can you point out four or five books that have become your favourites of the last year?

LAM: I’m still looking back on the prior year’s books and won’t get to properly digest this year’s harvest fully until the end of the summer and The Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation Prize. Every Autumn I’m inundated by the 1,000+ titles that get submitted. I see A LOT. But there are inevitably, a few that stand out, or that I return to repeatedly over time.

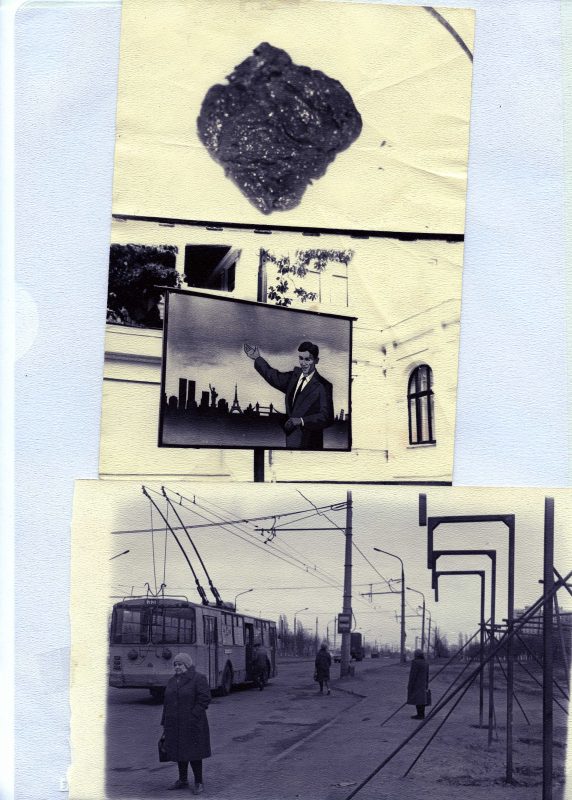

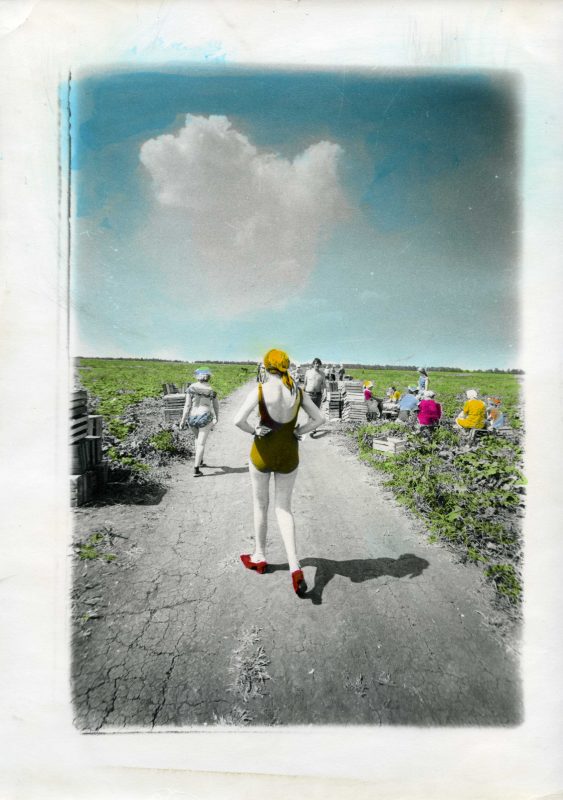

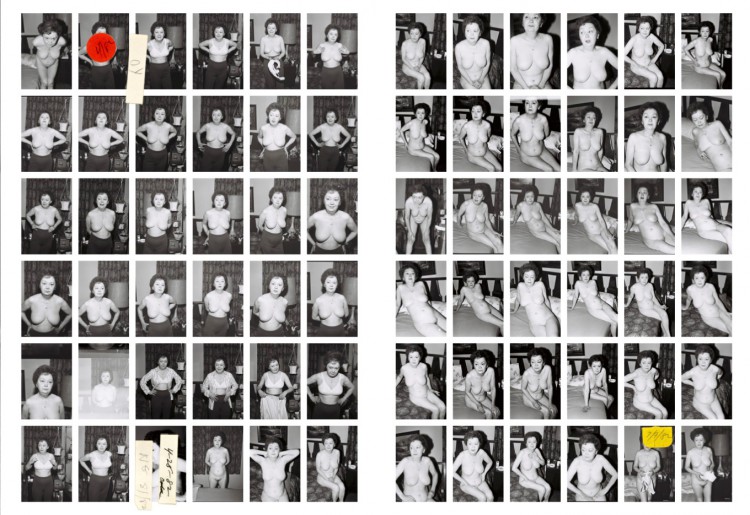

In the past year, those include Taking Off. Henry My Neighbor by Mariken Wessels, which is a very strange set of images collected by Wessels of one man’s obsessive photographing of his wife. Dana Lixenberg’s Imperial Courts, a document of one Los Angeles-neighbourhood over the course of twenty years also just gets better with repeat viewing. Both of these books – each very different in subject and approach but similarly predicated on a photographer’s long-term engagement with their subject – take pains to also be really remarkable physical objects, with particular care to with the printing, design, and structure of the material. Out of Order: Bad Display by Penelope Umbrico, is one of the artist’s iterative projects that returns to a prior book she created with RVB Books in 2014. Umbrico has become a really thoughtful about her books, folding the process of making them into her larger practice of making work, the unusual forms they take and the methods of their making are always directly tied-into the concepts within.

I also can’t help but be stupefied by the gorgeously printed re-issue and expansion (or, explosion) of William Eggleston’s Democratic Forest. As with the rest of Steidl’s insatiable drive to gobble up and put forth the archives of photographers living and dead, I’m a little ambivalent about whether or not to best categorise these as books or as furniture – it certainly is an excellent example of the collector-supported publication model. It’s quite an investment, at $600 per set. So while this skews the concept of a democratic anything, in terms of a flattening out the hierarchy of image-making, this material, of any, is best suited to the multi-volume, anti-edit approach. (I have to also confess that I may, in part, be conflating my appreciation for this book with my appreciation and enjoyment Prudence Ffeifer’s excellent review of the book in the May issue of Bookforum – the power of a great book review!)

JL: How much of the current state of photobook publishing do you perceive as artists believing books are the most viable vehicles to launch careers?

LAM: I often I see books made by artists that feel way too transparent in this regard – it’s as if every decision made in constructing the book was weighed against some external checklist of what’s worked for other people, rather than what’s right for the material itself. The use of different types of paper: check. Tipped-in facsimiles of vernacular material: check. Centred, sans-serif type that is underscored instead of italicised: check. There are certain design and format tics that seem to be contagious from year to year. Increasingly, people get hung up on creating over-the-top, bleeding edge design packages when something simple or pared down would be equally if not more suitable and successful. That said, there is so much room now for different ways of putting a body of work onto the printed page, it has led to some really stand-out books – both wildly innovative and more traditional books that have been able to launch careers or solidify reputations.

We’re seeing a dramatic shift in the gallery world, in which the smaller galleries are having a hard time of it – there is less space for showing and selling work, certainly less space for really being able to present an entire body of work, properly contextualised, which is what a book can do so well, and of course, a book can end up in anyone’s hands. A book of interesting work that has been done thoughtfully can certainly bring an artist to another level of attention. There are also a lot more books that I have a hard time wrapping my head around in terms of WHY. Why does this body of work exist in this form and what was the photographer or publishing thinking when they made those decisions? I’m all for borrowing, and great ideas often beget other good ideas, but not if they’re simply adapted without cause and clear intention. Really – more people asking WHY – why am I making this book? Does it need to be a book? And then figuring out the best way to take that forward would be really helpful. If you just want to make a book because it’s expected of you and you think it will help your career, you haven’t thought about it hard enough.

JL: Do you believe that even though there are more books published each year, the amount that are really noteworthy has remained perhaps the same as twenty to thirty years ago?

LAM: It’s tempting to think along these lines, and I’ve heard that line before. But when you think about it, the categories and types of books have opened up and changed so dramatically that surely that’s not the case. I mean, how do you evaluate a really great self-published item printed on newsprint against something like the aforementioned Democratic Forest. There are so many more points across a much wider map, there has to be both more and better, don’t you think? They won’t all operate the same way in terms of pushing an artist or a set of ideas forward, and lots will get missed. But I’d like to think optimistically and to believe that there are more, better publications being made across a wider range of possibilities. Of course, there are going to be equivalent larger numbers of worse books getting made as well – and that can be depressing and a little brain-numbing. This is why I’m all for a network of signposts that can help navigate the overload of books – blog posts on sites like itsnicethat.com, selfpublishbehappy.com, the fantastic vimeo feed from photobookstore.co.uk, Instagram feeds like @10 x10; and tags like #photobookjousting – that’s just a few.

JL: What appeals to you as an editor, when an artist approaches with a ‘finished’ dummy or would you prefer to see the raw material? I am assuming you are open to both ways. Can you estimate a percentage of each?

LAM: It’s so case-by-case and changes season by season. In an upcoming season of six monographs for Spring 2017, none of them came as already formulated dummies. The Autumn 2016 season, three of five books came as dummies. I think it’s helpful for an artist to wrestle with the problem of how to make something into a book, but not helpful for them to get hung up on wanting to control every detail, but to allow room for collaboration and input.

JL: Do you have opinions about publishers who are essentially shifting their role to becoming mainly distributors – taking on projects by photographers who pay a premium of the entire book production and beyond to publish their book.

LAM: There are several sides to this – first, I have to state Aperture’s position on the matter. We do not ask artists to write cheques to fund their books. However, we do have to raise the money for each and every title that we don’t see succeeding exclusively on sales in the mainstream book trade. That usually means a there is a collaborative effort that goes into figuring this out – whether it’s jointly mounting a Kickstarter campaign, to applying for grants, appealing to collectors and our patrons, or selling prints. And it is often a combination of the above.

But I also want to point out that this trend has to be seen, in part, in relation to how the roles have been redistributed across the board. Photographers are increasingly casting themselves as designers and editors so books are coming to a publisher already digested and the decisions that a publisher would usually help guide – what the book looks like and how it needs to be printed and bound, and thereby, what the budget and corresponding price point can or should be, are increasingly claimed by photographers. Along with those decisions come risks and repercussions. Essentially, photographers are becoming co-publishers as much as the simply authors. I’m not saying this makes it all come out fine in the wash, but I don’t think you can ignore that all of these roles function in relation to one another. You push one piece of the puzzle and something else gives way. It’s a reminder that very few of the traditional roles or rules about how publishing worked remain hard and fast anymore and we have to keep moving and evolving.

JL: Have you felt any photobook oversaturation or ‘burn-out’ in these last years either with publishing or photobook festivals?

LAM: I am very aware that the photobook community can easily find itself in conversations that are too much of a closed system, that are less about the work and the world and more about the book (and often arcane details of a particular book) as one tool for exploring and experiencing photography. It can be a little limiting and insular, absolutely. But I also love the obsessiveness and attention to detail and craft that the book community currently hosts, and I believe that a language and body of knowledge around the photobook is in the process of being built – one that has become an important, accepted part of the larger dialogue of photography. The idea that the circulation of an image or a body of work – and in particular it’s circulation on the printed page – is an important part of its history and our understanding of it. And this seems solidly established for the time being. But we have to keep looking forward and as photography continues to change, we know that forms of storytelling and experiencing images – habits of literacy of all kinds – are in the process of changing as well. So, I don’t feel that the level of activity we’re currently at will be sustainable if photobook making and photobook festivals do not continue to evolve. For now, though, this network of fairs is an important means of exchange and commerce – how long it can last is certainly a question I ask myself all the time.

And as for me, I personally reach a certain point of hyper saturation in late November, once the New York Art Book Fair is over, once The Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation Prize has been awarded, Paris Photo and Offprint are over and all the “Best of” blogs have been read – when I don’t think that I could possibly look at one more book. But somehow, by January, I find myself picking books up again, drawn by a particular cover or wanting to see what a certain binding material feels like, wondering what’s inside, and what else is out there. Hopefully those impulses – in myself and in others – will continue to be refreshed and rewarded by new, exciting creations and developments in this still-evolving field. ♦

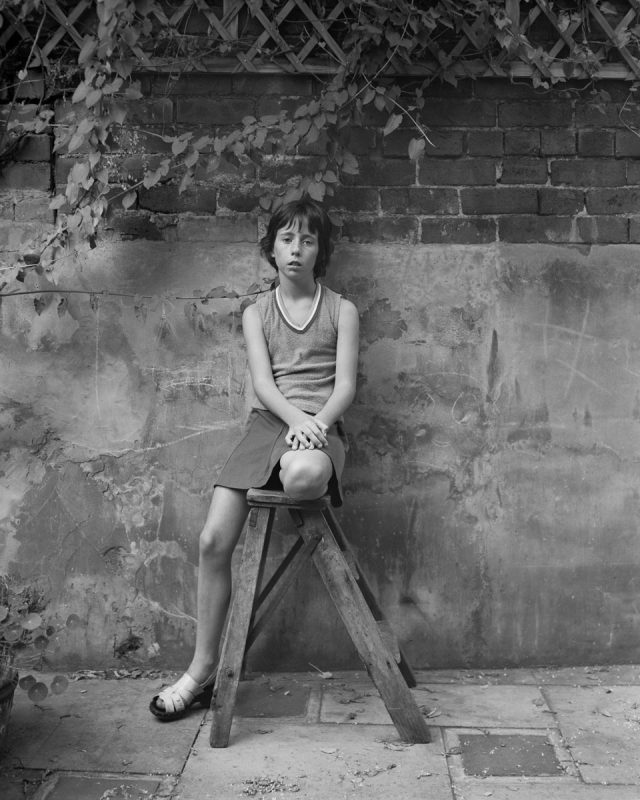

Image courtesy of Lesley A. Martin © Carlo Van de Roer