Silvia Rosi

Disintegrata

Exhibition review by Mariacarla Molè

Silvia Rosi’s exhibition at Collezione Maramotti in Reggio Emilia showcases 34 artworks across four rooms, unified by the theme of vanishing identity and fractured representation. The collection features photographs from families of African descent in the Emilia Romagna region of Italy that portray the vitality and resilience of the diaspora community. Through her art Rosi serves as a conduit to this history as she connects to the story contained in her family album, reports Mariacarla Molè.

Mariacarla Molè | Exhibition review | 20 June 2024

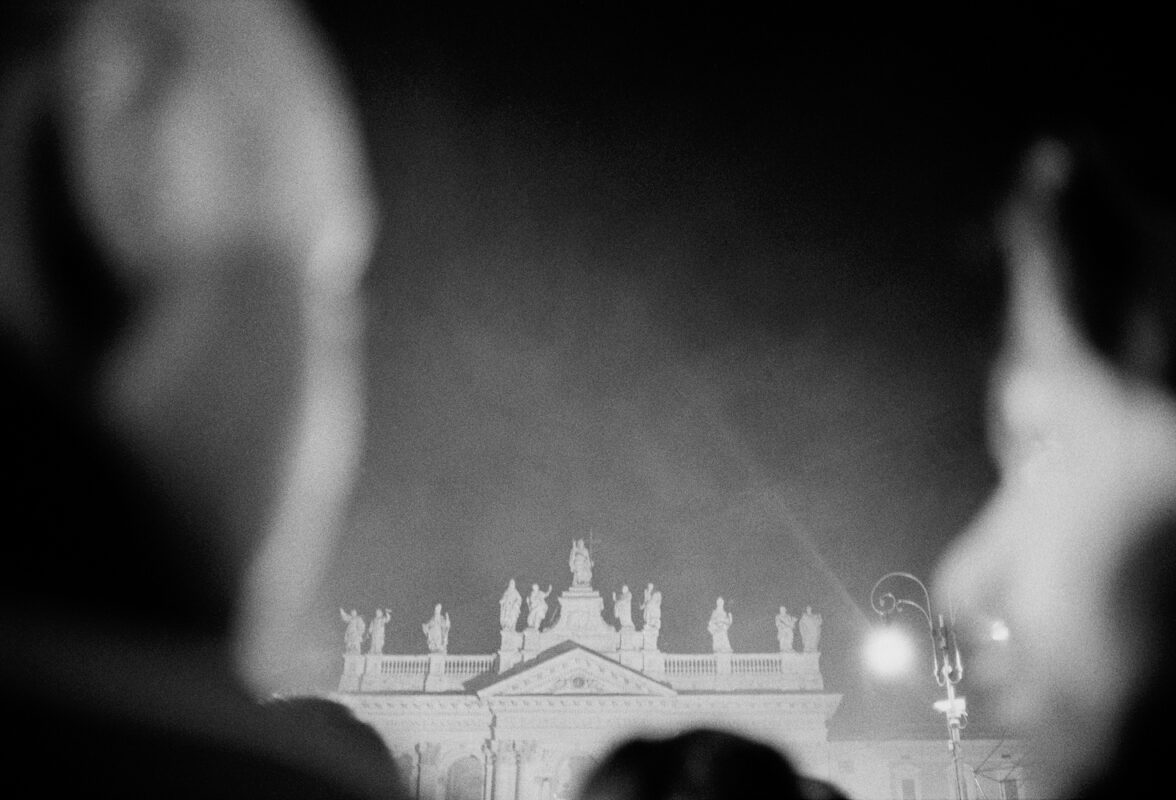

As a viewer of Silvia Rosi’s Disintegrata at Collezione Maramotti in Reggio Emilia, you become aware of the urge to piece together parts of a whole. The 34 artworks displayed in the four rooms appear to tell four distinct stories, yet they all share a common concept: the disappearance of a clear-cut representation of identity, which in turn becomes disintegrated, as implied by the title. Consequently, the exhibition presents photographic and video works that, despite being united by the word ‘disintegrata’, have a strong fragmented quality that is dispersed throughout the four rooms.

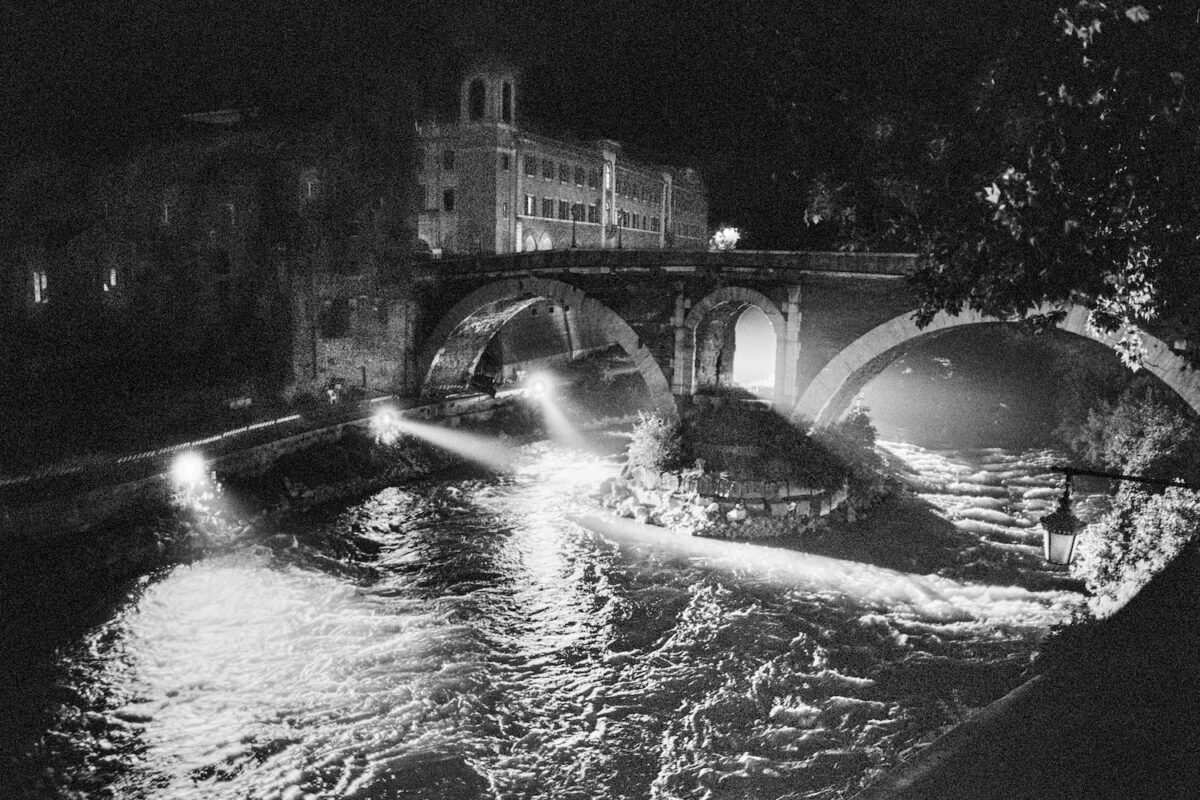

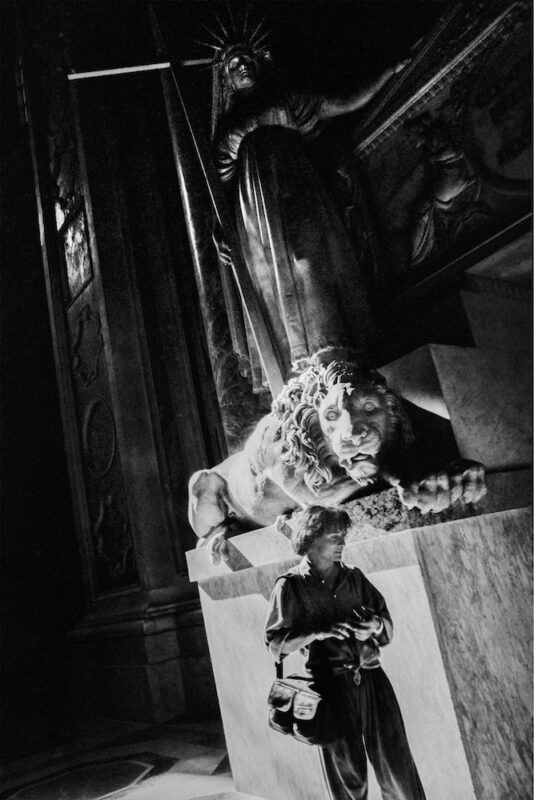

At first glance, the landscape photos in the initial room may leave you feeling disoriented, since the overall exhibition is billed as a project featuring archival photographs of the African diaspora in Italy, which the artist collected between 2023 and 2024. In fact, the first room is predominantly filled with black and white as well as coloured landscape photos, alongside videos, all from the series titled Disintegrata nel Paesaggio. These works mostly consist of images of Rosi’s figure crossing deserted green landscapes from the edge of time. The green colours are vibrant in the giclee prints, while the videos remain silent. In this scenario, the human figure seems unable to assert itself on the landscape; it can only pass through it. However, even when the human figure is caught posing, it appears to blend into the landscape: in one image, a figure with their back turned stands against a grassy landscape, and the texture of their coat merges with that of the grass. In another image, Rosi lies on the grass in the same coat, seemingly completely engulfed by it.

The desire to explore the landscape is new in Silvia Rosi’s practice and can be traced back to the theme of Fotografia Europea 2024, of which Disintegrata is a part: La natura ama nascondersi (Nature loves to hide), quoting Heraclitus, which assembles a series of solo and group exhibitions that thematise the sense of interdependence of every life form on Earth as part of a larger living organism. Some other elements resonate with those familiar with Rosi’s work, such as the tension of removing disturbing elements from the background, the coexistence of colour and black-and-white and her own presence, even if it is particularly elusive here, as if to underline the frustration towards self-portraiture and self-representation which becomes more and more slippery. Perhaps a clue to the direction her work is taking?

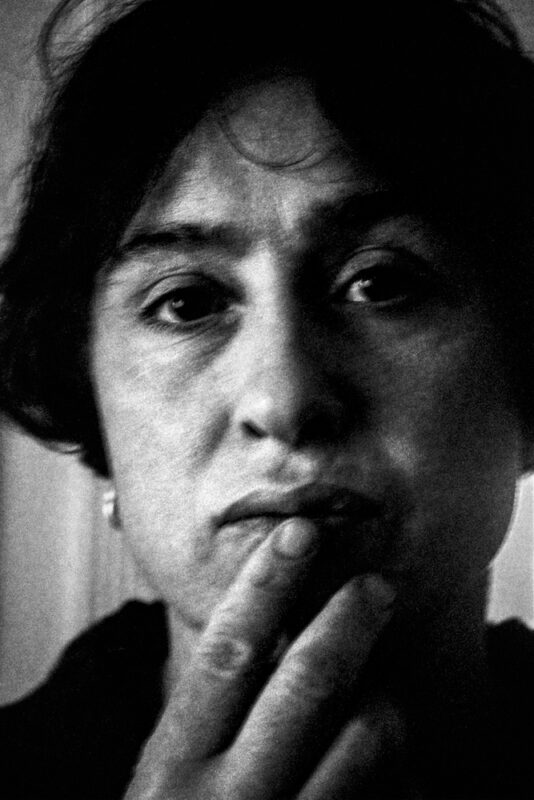

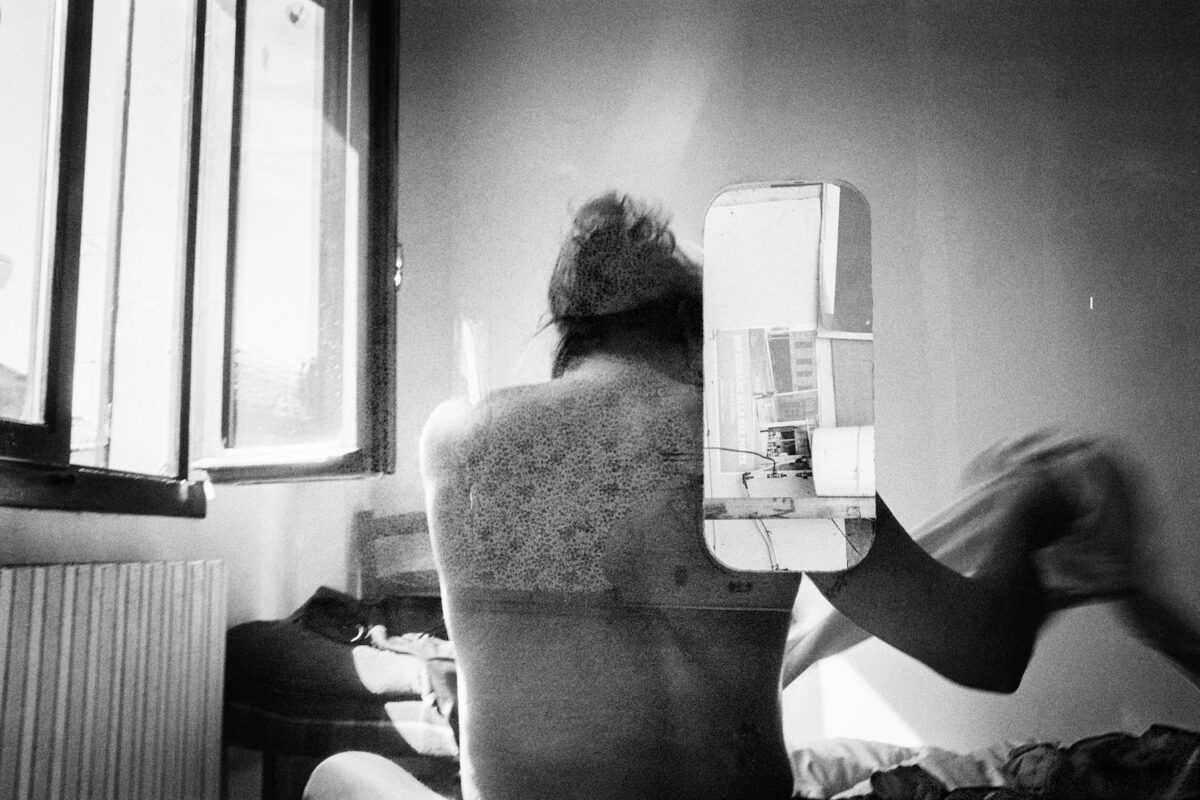

In the second room, it is easier to recognise Rosi’s work as it can be traced back to her analogue studio portraiture, which she then digitises, not to mention the clearly visible self-timer cable which is another characteristic element of her self-portraiture. The images constructed in the studio make use of single-colour drapes or essential decorations with geometric black-and-white patterns on the floor, such as checkered rhombuses and dots, and elegant outfits. In one image, Rosi shows off a wedding dress, in another a wig, and in another an elegant trouser suit. These are all meant to demonstrate adherence to specific historical periods – the first: the 1990s when her parents moved from Togo to Italy, and the second: studio portrait photography of 60s post-colonial West Africa. The environment of each image is bare, inhabited only by Rosi and individual objects such as a bike, a wedding dress, bedside tables loaded with framed family photos, an old hairdresser’s helmet and two old suitcases. All of these elements were extracted from Rosi’s family album to be reactivated with a stage-like quality. Reading the captions pays off as each self-portrait is a version of her ‘disintegrated’ presence. When translated, the titles read ‘Disintegrated with Family Photos’, ‘Italian Bride Disintegrated’ and ‘Disintegrated in Profile’, which represent splinters of possible worlds. Her figure, although omnipresent, seems to want to escape from the camera, often with her back turned or her face hidden behind objects like a flower, a shoulder, a helmet or a pack of Agfa photographic paper. The reference to Malick Sidibé’s photography is clear. However, unlike the photographer who used objects to reveal the pride of his portrayed subjects, Rosi uses them as a portal through which to connect to the story contained in her family archive. This allows her to pose in her parents’ clothes, so as to discover the history of her family, starting from the photographs in her album, through her body and the history of the diaspora, which was kept silent for a long time. She only experienced the aftermath of this history.

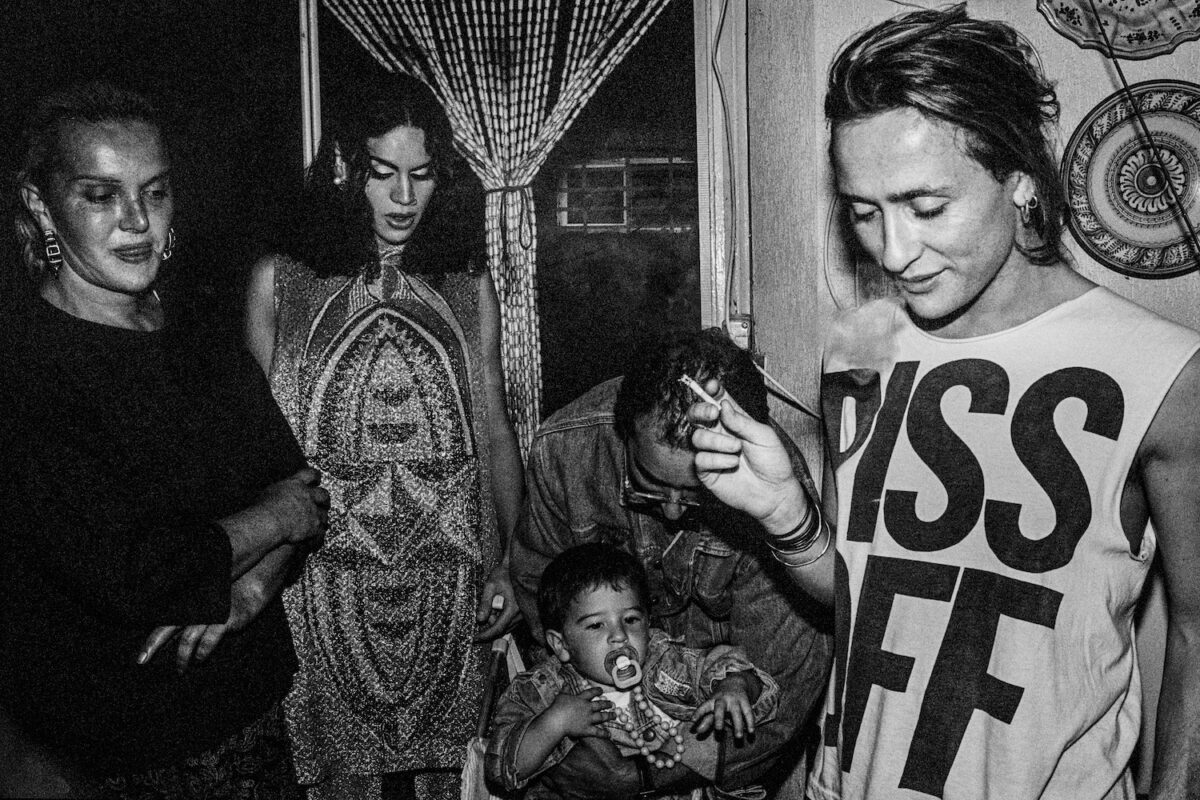

The interest in family albums is reignited in a collection of photographs from the 90s that Rosi, along with a team of researchers, gathered from families of African descent in the Emilia Romagna area, where she hails from. Palpable is the desire to create a disintegrated archive in a national territory that comes together via an openness to share and donate personal images. As someone who grew up in the early 90s, these poses and scenarios are very familiar: scenes of trips out of town, standing and posing in front of a landscape, in the centre of a square, or leaning against a car. Moments of celebration or simple daily life. The vitality is feverish, and they seem to say: “We are here and we are fine.” From the collection of work that Rosi amassed with the researchers, it emerged that these photos were often sent to relatives in Africa, accompanied by audio cassettes in which they recounted their stories. And this element seems to spill over into the video housed in the last room, where a three-part split screen shows a tape recorder on one side, with Rosi listening to the recorded voice through the headphones on the opposite side, while in the middle, the voice transcription of four different letters written between 1982 and 2000, read by the people who received them, telling stories of diaspora. You can sense their discomfort in speaking French, since it is not their first language. As a result, the communication might not be very fluent, but it is always sincere. They express gratitude, poverty, determination and worry. At this point, you feel conscious of being invited to assemble pieces, like an interpreter in photographs and a listener in videos, as Rosi seems to be doing to the world around her. ♦

All images courtesy the artist and Collezione Maramotti. © Silvia Rosi

Disintegrata runs at Collezione Maramotti, Reggio Emilia, until 28 July.

—

Mariacarla Molè is an art writer based in Turin.

1000 Words favourites

• Renée Mussai on exhibitions as sites of dialogue, critique, and activism.

• Roxana Marcoci navigates curatorial practice in the digital age.

• Tanvi Mishra reviews Felipe Romero Beltrán’s Dialect.

• Discover London’s top five photography galleries.

• Tim Clark in conversation with Hayward Gallery’s Ralph Rugoff on Hiroshi Sugimoto.

• Academic rigour and essayistic freedom as told by Taous R. Dahmani.