Les Rencontres d’Arles 2024

Beneath The Surface

Festival review by Mark Durden

For the 55th time, Arles, the historic Roman city in southern France, hosts the prestigious Les Rencontres d’Arles, where municipal buildings are transformed to showcase the visual legacies of photographers and artists worldwide. This year’s theme, Beneath the Surface, explores narratives that uncover divergent paths, often revealing vulnerabilities in seemingly impermeable facades. As expected, the festival boasts its usual grandeur, meticulous organisation, and impressive works by renowned artists. Yet, as Mark Durden writes, it is the traditional photographic approaches that retain a profound impact amidst the festival’s exploration of new directions in the medium.

Mark Durden | Festival review | 11 July 2024 | In association with MPB

Sophie Calle’s exhibition of some of her own artworks and possessions are left to rot in the subterranean Cryptoporticus in Arles, offering a great contrast to the clamouring image spectacle of the very festival of which it is part. On discovering one of her favourite works, The Blind, had become toxic through mould spores after her studio was damaged in a storm, and refusing to follow the restorer’s suggestion that it should be destroyed, Calle decided to exhibit it (together with other works that had been contaminated and objects from her life that she no longer had any use for but could not throw away) in a humid and underground place where its degradation could continue. Calle’s show, in this respect, offers a mini retrospective, a darkly comic counterpoint to the grandiosity of more spectacular displays above ground, and a reminder of the ultimate and inevitable mortality of art and the artist. When I viewed her exhibition, water was constantly dripping upon large framed black-and-white prints of graves, laid on the floor.

This year’s Les Rencontres d’Arles is marked by a schism between those who work against photography, those who deploy it through montage in installations and those who less ostentatiously explore its intrinsic properties. Calle works against photography, but knowingly and comedically, clearly relishing the correspondence between her decaying pictures and their sepulchral and funerary setting.

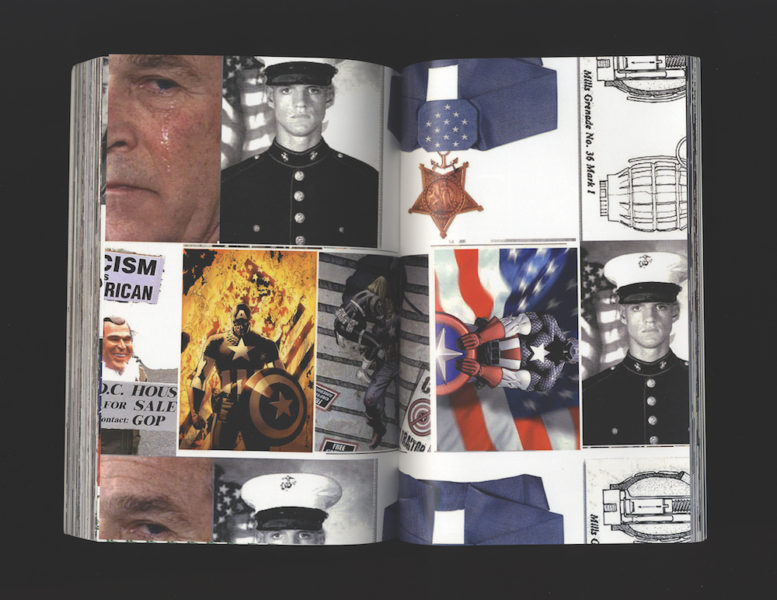

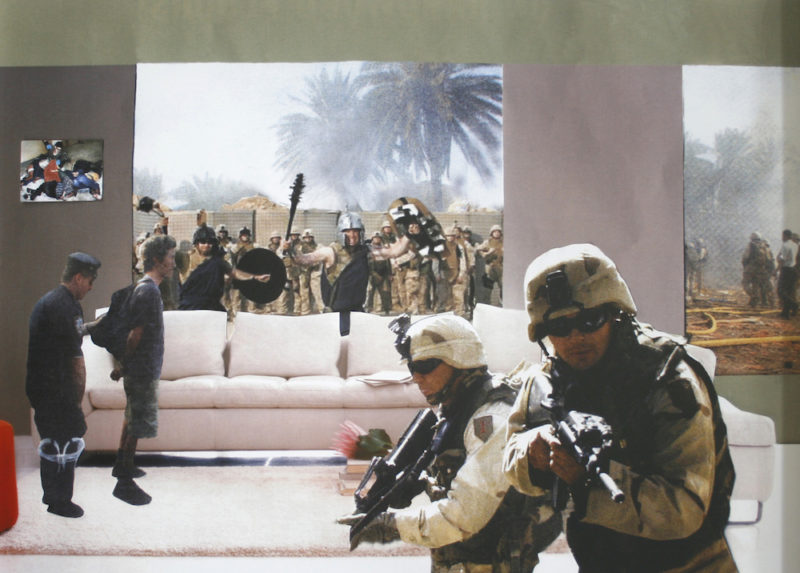

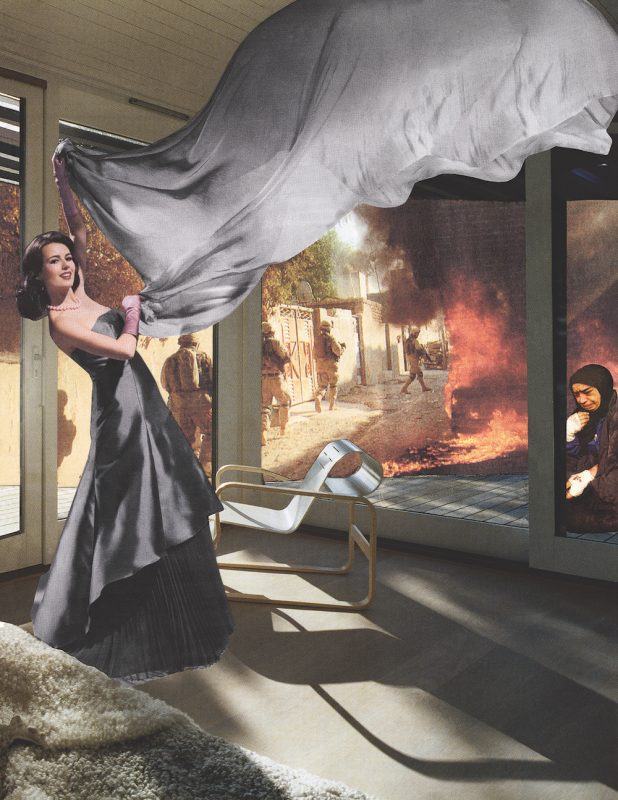

In the impressive interior of the 15th century century Gothic Église des Frères Prêcheurs, Spanish photographer Cristina de Middel’s flagship show’s magical realist response to the migration route across Mexico to the US, with its overblown and enigmatic combinations of pictorial elements, objects, archival material and Mexican lotería card imagery (this game of chance, presumably there to bring in an iconography related to Mexico and imply the journey of migrants is a lottery and up to fate) muddles the clarity of reportage and seemingly relishes the resultant ambiguity. The US’ brutal migrant policy and murderous exploitation by cartels through both people and drug trafficking (nothing to do with chance) becomes a cue to a fantastical tale, modelled on Jules Verne’s science fiction Journey to the Centre of the World (1864). The problem with such a spectacular display is that it is hard to engage and relate to what is going on as images collide and compete for attention. If montage was originally intended to be critically dialectical and produce new meaning, the danger here is that things become all too uncertain.

Mary Ellen Mark, who is given a significant and engaging retrospective at Espace Van Gogh, valorises an older, humanist documentary tradition; her 1987 portrait of the Damm family in the car in which they were living at the time, is in some ways her “Migrant Mother”. Perhaps it is not so obsolete as de Middel’s pop documentary display might suggest. The real goes beyond our imagination, and is always full of surprises. Photographers like Mark are attuned to this and bring it out again and again in many of their extraordinary pictures. In her powerful, colourful, somewhat voyeuristic depictions of sex workers in Mumbai, she may be outside but the sense is that she pictures more from the inside and in affinity with these women. At the Palais de L’Archevêché, I’m So Happy You Are Here, Japanese Women Photographers from the 1950s to Now curated by Lesley A. Martin, Takeuchi Mariko and Pauline Vermare, was a welcome change and far cry from the continued celebration of such male Japanese photographers as Daido Moriyama and their fixation on women as subject. But with so many photographers on show, 26, it only functions as a taster. I would have liked to have seen more work by Mari Katayama. Born with tibial hemimelia, which caused the bones in her lower legs and left hand to be undeveloped, and having decided to amputate her legs at the age of nine, the young artist sees herself as ‘one of the raw materials to use in my work’ in extraordinary self-portraits with hand-sewn prostheses.

Ishiuchi Miyako, recipient of the Women in Motion Award, as well as showing in I’m So Happy, is given a solo show at the Salle Henri-Comte, presenting photographs of objects and possessions remaining after death: her mother’s used lipstick, her lingerie, her hairbrush tangled with her hair, her dentures. There is also a picture of her mother’s scarred skin. For Miyako, ‘things touched by my mother were like part of her skin.’ The intimacy and poignancy of such photographs is continued in other pictures: the clothing and personal objects of Atomic bomb victims, from the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, and Frida Kahlo’s belongings, her nail varnish, decorated corsets and casts, through which one can sense the presence and strength of the artist. Miyako is responsive to the intrinsic properties and resonances of photography as an auratic medium. In contrast to Calle’s funereal retrospective, for Miyako, objects from the past, through photography, are ‘revived in the present moment.’

In many ways, New Farmer (2024) by Bruce Eesly offers a bright, jaunty and comic interlude to the festival; an AI generated mock documentary, consisting of photographs and texts presented as if from the 1960s, parodying the Green Revolution’s goal of intensified agricultural yields, by showing farmers, fields and smiling kids replete with oversized vegetables. Such absurdity and fakery serves as a fictional counterpoint to the reality of what increasing farming yields has led to, as the artist says: ‘giant fields of monocultures, fertiliser run-off, pesticide pollution and a major loss of genetic plant diversity.’

The revelation of Nicolas Floc’h’s exhibition is that there is a rainbow of colours in water. His epic quasi-scientific project, Rivers Ocean. The Landscape of Mississippi’s Colors (2024), a dazzling array of different blocks of pure colour prints, the result of photographs taken underwater at different depths, presented together with black-and-white photographs of the land, nevertheless remained baffling. While the descriptive detail in some of the captioning texts might help explain what causes the colours – ‘In Minneapolis, the Mississippi gets its colour from the tanins of northern forests… At the surface, a bright luminous orange turns bright red at one to two meters in depth’ – in the end, I was left pondering the gulf between these beautiful and seductive colour fields and the pollution and ecological disaster they presumably are indexing.

At La Mécaniqué Générale, there is more colour, not so much in the photography, which is predominantly black-and-white, but on the walls that animate and resist the potential stasis of ordered clusters of photographs in Urs Stahel’s beautifully curated show, When Images Learn to Speak, drawn from the collection of Astrid Ullens de Schooten Whettnall. Since the collector has been buying up whole series rather than individual photographs, Stahel pursues the conceptual implications of serial groups of images, beginning with Harry Callahan’s street portraits and Walker Evans’ worker portraits. The show is very much about the formal richness, the subtleties and lasting fascination with what are mostly now classic photographs. There are also some nice surprises, including Max Regenberg’s billboards, for example, in both colour and black-and-white, taken over two decades, a simple register of fortuitous collisions and relations between the imagery of billboards and their settings: the crumpled rear end of a car appearing as if trampled by giant feet on the advertising beside it. Is there not a lesson for Arles here? Maybe we do not need the fireworks. Straight(-forward) photography can still be very engaging and lasting.

Stahel’s curation links well with Lee Friedlander’s small survey show at LUMA. Friedlander was also in Stahel’s show and some of his TV pictures appear in both exhibitions. An outlier to the festival, the Friedlander exhibition nevertheless was a vital and refreshing addition. Selected and curated by filmmaker Joel Coen, the show underscores the enduring richness of his work and brilliant understanding of the possibilities of photographic form. Coen is skilled in picking out the compositional play of elements in well-known and lesser-known Friedlanders. The point made by Friedlander in the 1960s was that montage effects can already be found in the world; it is a question of framing. He is a picture-maker who made a virtue out of the limits of photography. A pity there are so few new contemporary photographers on show at Arles that come close.♦

Les Rencontres d’Arles 2024 runs until 29 September 2024.

—

Mark Durden is an academic, writer and artist. He is Professor of Photography and the Director of the European Centre for Documentary Research at the University of South Wales. He works collaboratively as part of the artist group Common Culture and, since 2017, with João Leal, has been photographing modernist architecture in Europe.

Images:

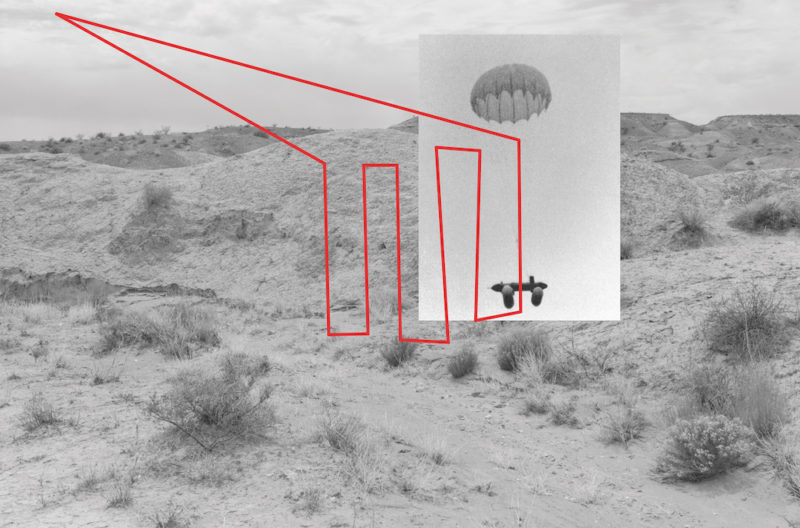

1-Sophie Calle, Finir en Beauté, 2024. Courtesy Anne Fourès

2-Cristina de Middel, An Obstacle in the Way [Una Piedra en el Camino], Journey to the center series, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Magnum Photos

3-Cristina de Middel, The One That Left [La que se Fue], Journey to the center series, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Magnum Photos

4-Cristina de Middel, The Black Door [La Puerta Negra], Journey to the center series, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Magnum Photos

5-Mary Ellen Mark, Rekha with beads in her mouth, Falkland Road, Mumbai, India, 1978. Courtesy of The Mary Ellen Mark Foundation and Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

6-Mary Ellen Mark, Vashira and Tashira Hargrove, Suffolk, New York, 1993. Courtesy of The Mary Ellen Mark Foundation and Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

7-Mary Ellen Mark, The Damm family in their car, Los Angeles, California, 1987. Courtesy of The Mary Ellen Mark Foundation and Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

8-Rinko Kawauchi, Untitled. From the eyes, the ears series, 2002-04. Courtesy the artist and Aperture Foundation

9-Sakiko Nomura, Untitled, 1997 from the Hiroki series. Courtesy the artist and Aperture Foundation

10-Hitomi Watanabe, Untitled from the Tōdai Zenkyōtō series, 1968-69. Courtesy the artist and Aperture Foundation.

11-Ishiuchi Miyako. Mother’s #35. Courtesy the artist and The Third Gallery Aya

12-Ishiuchi Miyako. ひろしま / hiroshima #37F donor: Harada A. Courtesy the artist and The Third Gallery Aya

13-Bruce Eesly, Peter Trimmel wins first prize for his UHY fennel at the Kooma Giants Show in Limburg, 1956. From the New Farmer series, 2023. Courtesy the artist

14-Bruce Eesly, Selected potato varieties are rated in sixteen categories according to the LURCH Desirable Traits Checklist, 1952. From the New Farmer series, 2023. Courtesy the artist

15-Bruce Eesly, Farm table in Dengen, 1955. From the New Farmer series, 2023. Courtesy the artist

16-Nicolas Floc’h, White River, Badlands, South Dakota, Rivers Ocean. From the Mississippi series, 2022. Courtesy the artist

17-Nicolas Floc’h, Sioux Falls, South Dakota, Rivers Ocean. From the Mississippi series, 2022. Courtesy the artist

18-Nicolas Floc’h, Gulf of Mexico, Louisiana, Rivers Ocean. From the Mississippi series, 2022. Courtesy the artist

19-Nicolas Floc’h, Mississippi River, Minneapolis, Minnesota, Rivers Ocean. From the Mississippi series, 2022. Courtesy the artist

20-Moyra Davey, Subway Writers III, 2011. Courtesy the artist

21-Martha Rosler, Photo-Op, photomontage. From the House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home series, 2004. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin/Cologne/Munich

22-Judith Joy Ross, Annie Hasz, Easton, Pennsylvania, Protesting the Iraq War, Living With War. From the Portraits series, 2007. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Thomas Zander, Cologne

23>24-Courtesy Lee Friedlander and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco and Luhring Augustine, New York.

1000 Words favourites

• Renée Mussai on exhibitions as sites of dialogue, critique, and activism.

• Roxana Marcoci navigates curatorial practice in the digital age.

• Tanvi Mishra reviews Felipe Romero Beltrán’s Dialect.

• Discover London’s top five photography galleries.

• Tim Clark in conversation with Hayward Gallery’s Ralph Rugoff on Hiroshi Sugimoto.

• Academic rigour and essayistic freedom as told by Taous R. Dahmani.