Agnieszka Sosnowska

För

Book review by Shana Lopes

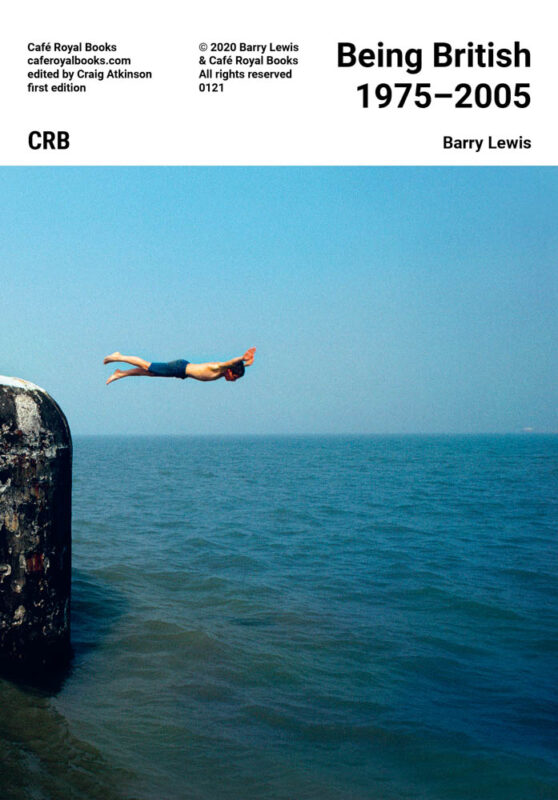

Published by Trespasser, Agnieszka Sosnowska’s debut monograph, För, is a coming-of-age story about relocating a remote corner of Iceland, which introduces us to her students, showcases her farm, and captures the passage of time as she and her husband age over two decades. As SFMOMA’s Assistant Curator of Photography Shana Lopes writes, Sosnowska invites us to rethink how labour, heartbreak, death, landscape, and the quotidian contribute to an idea of home.

Shana Lopes | Book review | 18 July 2024

A reindeer decomposing on the ground; white sheets hanging outside to dry; a man bathing in an outdoor tub: moments of quiet flow through Agnieszka Sosnowska’s pictures in her sumptuous first book, För, recently published by Trespasser. By virtue of their objecthood, all photographs are inherently silent, yet many evoke the sounds of whoever or whatever is pictured. Sosnowska’s vision offers a distinctive sonic experience of blustery winds careening through a rural landscape, bitterly cold water pouring down a cliff face, hushed conversations between people who have known each other for decades. And while many of her photographs point to stillness, the sequencing of the book, though nonlinear, is rhythmic, its cadence at once brooding and hypnotic, rapturous and meditative. Self-portraits form the chorus to this poignant ballad in black and white, bridged by stark, dramatic landscapes, unpretentious domestic still lifes, and pictures of students, friends, and family at ease. We may think we listen only with our ears and look solely with our eyes, yet we also sense with our bodies, and these Icelandic scenes exude the briskness of their unforgiving environment. Even the book’s exterior adds to the overall experience. It is bound in a cool bluish-gray cloth, the colour I imagine Iceland’s sky and water look like. It depicts a world of raw beauty that asks us to be present and attuned with all our senses.

Much of the power of Sosnowska’s photographs, the majority taken with a large-format film camera, resides in their uncluttered simplicity. Clean lines guide our eye, but the scenes are neither immaculate nor pristine. They are lived in, revealing signs of aging, even decay: a rusted car door, the well-worn cushions of a couch, a pile of old, used tires. Every one was captured near the artist’s home in eastern Iceland, where she has lived and worked as an elementary school teacher for more than two decades. Originally from Poland, she immigrated to the United States as a child, then as a young adult visited Iceland on a whim and fell in love there.

The book’s title – För – translates as “trip” in Icelandic, and so signifies a journey and the physical imprints one leaves behind. The word also connotes a vessel that delivers things from one location to another. So, what are these photographs transporting? What kind of trip is Sosnowska taking us on, and what traces has she left behind for us to follow?

This is certainly a journey of belonging, of making a home, and it is raw, authentic, and unpretentious. Sometimes intensely intimate. Consider, for example, the photographs of the artist and her husband. In one, he stands behind her, his hand inside her button-front dress, as she stares unabashedly at the camera. In another sublime moment, they pose before a misty waterscape like a modern Caspar David Friedrich painting, the view so awe-inspiring and powerful that their presence becomes secondary to the terrain. These pictures are not about tourism. Rather, they take us on an expedition of Sosnowska’s life. We meet her students; we see her farm; we watch her and her husband, whom she calls her Viking in the acknowledgments, age over the course of 20 years. I find myself wondering why she is publishing her first photobook now, if she has been shooting for this long and her photographs are this incredible. Indeed, her training harks back to the 1990s, when she studied at the Massachusetts College of Art with professors such as Barbara Bosworth, Nicholas Nixon, Frank Gohlke, and Abe Morell. But that is a story for another time. För centers the artist’s Icelandic journey and asks us to reflect on our own paths and the imprints we leave.

A spellbinding landscape framed by a jigsaw-puzzle web of trees opens the book. Soft grasses line the foreground, and beyond the arboreal lattice we see a seemingly boundless terrain. The photograph is a literal and metaphorical entrance to our trip as well as a portal into Sosnowska’s mind. It is also a landscape shaped by humans, which seems to be a key theme running through the publication: human versus nature, or perhaps more aptly, with nature. The photographs in För often depict coexistence and interaction between humans and the natural environment, highlighting the beauty and fragility of this relationship.

What truly stands out in this beautifully edited grouping (a hallmark of Trespasser’s publications) are the self-portraits. Vulnerable and unapologetically authentic, they function like punctuation, little reminders to pause and remember whose journey this is. Sometimes Sosnowska is alone, other times she is accompanied by her husband. In watching them grow older, we witness them undergoing life’s most humbling experience. The artist’s face and body change, as does her relationship with the camera, as she moves from performing for it to collaborating with it. These self-portraits are a testament to the artist’s personal evolution and its reflection in her work.

Together, the pictures show us what home means to Sosnowska: the people, the place, the architecture, the small details. She notes, ‘By taking these pictures, I belong. I am part of something greater than myself. These photographs are both my myths and truth. They are my love, hopes, fears, and strength.’ Home, for her, is not singular or fixed. We sometimes have the privilege of choosing a new home, and that place changes us. A trip to Iceland more than 20 years ago forever changed Sosnowska’s path, bringing with it a new language, an intense love, a teaching career, and a rural way of life. Ultimately, this book is a vessel detailing one artist’s search for a sense of belonging, inviting us to rethink how labour, heartbreak, death, landscape, and the quotidian contribute to an idea of home. It is a journey that resonates with our own quests for connection. ♦

All images courtesy the artist and Trespasser. © Agnieszka Sosnowska

För is published by Trespasser.

—

Shana Lopes is an Assistant Curator of Photography at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Born and raised in San Francisco, she earned her doctorate in art history from Rutgers University with a focus on the history of photography. Over the past fifteen years, she has gained curatorial experience at the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, Arizona, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. She has curated or co-curated exhibitions such as Constellations: Photographs in Dialogue, Sightlines: Photographs from the Collection, A Living for Us All: Artists and the WPA, Sea Change, Zanele Muholi: Eye Me, and the upcoming 2024 SECA Art Award.

1000 Words favourites

• Renée Mussai on exhibitions as sites of dialogue, critique, and activism.

• Roxana Marcoci navigates curatorial practice in the digital age.

• Tanvi Mishra reviews Felipe Romero Beltrán’s Dialect.

• Discover London’s top five photography galleries.

• Tim Clark in conversation with Hayward Gallery’s Ralph Rugoff on Hiroshi Sugimoto.

• Academic rigour and essayistic freedom as told by Taous R. Dahmani.