London city guide

Top five photography galleries

Selected by Tim Clark and Thomas King

As the dust settles on Photo London 2024 and Peckham 24 – the capital’s two key points of reference within the UK photography calendar – we benchmark five leading London galleries and museums who are making a sustained effort to create productive and welcoming spaces for the encounter, use and consideration of photography today.

Tim Clark with Thomas King | City guide | 14 June 2024 | In association with MPB

At a time when the funding climate in the UK is at its least favourable in decades, setting up – let alone sustaining – a gallery dedicated to the art of photography, public or otherwise, is far from straightforward. The sector is currently groaning under the weight of government funding cuts, exorbitant energy bills, messy logistical and bureaucratic ramifications arising from Brexit, the fallout of the pandemic and cost of living crisis; not to mention the constant undermining of the arts in education in favour of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) subjects at the hand of the outgoing Tory party, allied with pedalling culture wars and all round anathema.

Yet, despite – and even in spite of – these significant challenges, the UK government’s own estimates show that the creative industries generated £126 billion in gross value added to the economy and employed 2.4 million people in 2022 alone. A global leader clearly, but one that is woefully underfunded, leaving an increasing amount of arts organisations out to dry as they struggle to thrive in one of the world’s most expensive cities. In a parallel universe, the city of Berlin’s culture budget for 2024 is set at €947 million (with a population of 3.56 million) while the entire culture budget for England in 2024 pales in comparison at £458.5 million (with a population of 57 million): two wildly different per capita spends.

Meanwhile, in March this year, opposition party leader Kier Starmer spoke at the Labour Creatives Conference claiming he would “build a new Britain out of the ashes of the failed Tory project” and restore, what he called, the UK’s “diminished” status on the global stage. His top line pledges were as follows: getting art and design courses back on the curriculum, supporting freelancers’ rights, cracking down on ticket touting and improving access to creative apprenticeships. Essentially, promising to ensure creative skills are a necessity, not a luxury. To use the creative industries as a form of soft power. But it will require a detailed arts strategy coupled with fierce and charismatic advocates, and, crucially, increases in funding for the arts to European levels to get the UK’s cultural infrastructure back on sturdier ground. It is nothing short of a miracle, then, to have London gallery and museum spaces fully participating in a civic society at such a high calibre level.

What follows is a rundown of five leading London galleries and museums who are making a sustained effort to create productive and welcoming spaces for the encounter, use and consideration of photography today. It should be noted that there are a handful of medium specific spaces that haven’t been included, but doubtless could be. Among them: the ambitious British Centre for Photography currently looking for a permanent home; Tate, whose new Senior Curator of Photography and International Art, Singaporean Charmaine Toh, is just a few months in post; beloved and sorely missed Seen Fifteen (its founding director Vivienne Gamble now channels her energies towards growing the annual photography festival Peckham 24); Webber Gallery, which has seemingly shifted the emphasis of its exhibitions’ focus to a vast Los Angeles space; not neglecting to mention stalwart dealer Michael Hoppen whose eponymous gallery no longer operates from its multi-floor premises on Jubilee Place, instead opting for a location in Holland Park. Hopefully that goes some way to account for their omissions. There are other bricks and mortar spaces too: Hamiltons, MMX, Atlas, IWM’s Blavatnik Art, Film and Photography Galleries, TJ Boutling, Huxley-Parlour, Leica, Photofusion, Albumen, Purdy Hicks, Camera Eye, Augusta Edwards Fine Art and Doyle Wham, all worthy of a mention and giving much cause for celebration.

Autograph

Autograph

Rivington Place, London, EC2A 3BA

+44 020 7729 9200

autograph.org.uk

Every exhibition that Autograph stages is unmissable. The organisation’s remit is to ‘champion the work of artists who use photography and film to highlight questions of race, representation, human rights and social justice’, and it offers opportunity after opportunity to see powerful and vitally important work. Far from jumping on any bandwagon, this mission has long been embedded within the organisation, its practices and via ambitious work. Autograph was established in 1988 to support black photographic practices, and began in a small office in the Bon Marché building in Brixton, when it was known as the Association of Black Photographers (ABP). It applied for charitable status and moved to a permanent home at Rivington Place in Shoreditch in 2007, the first purpose-built space dedicated to the development and presentation of culturally diverse arts in England, decades before museums considered it necessary to start rethinking themselves.

Autograph punches significantly above its weight, and has long been an essential port of call for any photography lover living in or coming through the city, not to mention the impact on the capital’s culture at large. Largely owing to the skill and determination of visionary director Mark Sealy OBE – in post since 1991 – and talented and rigorous curator Bindi Vora, exhibitions at Autograph are born out of a professional methodology that is fundamentally interdisciplinary and grounded in both real-life research and experience. Yet it also moves past cultures of “them and us” to routinely bring to life transgressive and inclusive commissions, projects and publications.

As one of Arts Council England’s National Portfolio Organisations (NPO), Autograph saw a 30% uplift increase from £712,880 to £1,012,880 a year to support its work for the period of 2023–2026 (as per the last round of funding decisions announced in 2022). Stuart Hall once served as a chair on the board and Autograph’s unique collection contains works by Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Zanele Muholi, James Barnor, Lina Iris Viktor, Yinka Shonibare, Ingrid Pollard, Joy Gregory, Colin Jones, Phoebe Boswell, Raphael Albert, Ajamu and others.

V&A Photography Centre

V&A Photography Centre

Cromwell Road, London, SW7 2RL

+44 020 7942 2000

vam.ac.uk/info/photography-centre

Two transformative moments in the recent history of the V&A’s longstanding relationship with photography have been, firstly, the appointment of scholarly curator Duncan Forbes as the inaugural Director of Photography in 2020, who came from the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, and then the launch of The Parasol Foundation in Women Photography Project in 2022, spearheaded by the prodigious Fiona Rogers. Dedicated to supporting women artists though acquisitions, research and education, augmented through a commissioning programme with support from the Parasol Foundation Trust, Rogers’ programme also features an increasingly important prize established to identify, support and champion women artists. It attracted over 1,400 submissions for the 2024 edition produced in partnership with Peckham24.

Prior to this, its vast photography holdings were bolstered when the Royal Photographic Society (RPS) Collection was transferred in 2017, and the collection now runs to over 800,000 photographs that span the 1820s to the present day. Programmes have evolved amidst a backdrop of institutional accountability and inclusivity during the dramatic changes we’ve witnessed in recent years and has embraced dynamic contemporary practices as well as pivoted to account for the medium’s many histories. It’s now the largest space in the UK dedicated to a permanent photography collection, with a total of seven galleries, three rooms of which focus on contemporary international practices with Noémie Goudal and Hoda Afshar commanding ample space, the mighty impressive resource that is The Kusuma Gallery – Photography and the Book, and The Meta Media Gallery – Digital Gallery. Fledging curators: take note of The Curatorial Fellowship in Photography opportunity, supported by The Bern Schwartz Family Foundation, aimed to facilitate in-depth research into under-recognised aspects of the photography collection.

The Photographers’ Gallery

The Photographers’ Gallery

16-18 Ramillies St, London, W1F 7LW

+44 020 7087 9300

thephotographersgallery.org.uk

While the restrictive nature of its building – a converted, six story former textiles warehouse situated off Oxford Street in the heart of Soho – doesn’t make for an optimum exhibition experience, The Photographers’ Gallery remains an important and well-visited public gallery for photography in London. TPG spaces are tricky given the premises’ vertical orientation and warren-like galleries, but recent exhibitions such as the exemplary Daido Moriyama: A Retrospective, guest curated by Thyago Nogueira of São Paulo’s Instituto Moreira Salles, did well to turn the entire gallery into something coherent.

Founded by the late Sue Davies OBE (1933-2020) in 1971 as the UK’s first public gallery dedicated to photography, TPG has a strong legacy and recently saw is funding maintained at £918,867 per year as one of Arts Council England’s NPOs during the 2022 announcement, the same year it launched its outdoor cultural space, Soho Photography Quarter – a rotating open air programme with much potential. It’s the world-class education and talks offer, programmed and curated by Janice McLaren and Luisa Ulyett, that are among its standout qualities. Workshops and short courses are just some of the events that broaden access and steer conversation. At street and basement level there is an innovative Digital Wall catering for photography’s increased automated and networked lives, a print sales gallery, well-stocked bookshop and much-loved café area providing a condensation point for a range of different publics. TPG’s annual exhibition, The Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize, an award of £30,000, has also entered a new phase since 2020 to include a broader range of voices as evidenced by the past five winners: Mohamed Bourouissa, Cao Fei, Deana Lawson, Samuel Fosso and Lebohang Kganye.

Former Photoworks director Shoair Mavlian took the helm in 2023, positive news given her curatorial background, NPO experience and canny thought leadership. Of course, it takes a couple of years for a new incumbent to put their stamp on a place like this but TPG is primed to reap the benefits of Mavlian’s ethos – contemporary, generous and diverse – and question what the space can be and who it can be for in order to thrive into the future.

Large Glass Gallery

Large Glass Gallery

392 Caledonian Road, London, N1 1DN

+44 020 7609 9345

largeglass.co.uk

In 2011, former director of Frith Street Gallery, Charlotte Schepke established a contemporary art gallery that leans heavily into photography: the innovative and elegant Large Glass Gallery based near Kings Cross on the edge of central London. Large Glass bills itself as an ‘alternative to the mainstream commercial gallery scene’, a description that is wholly warranted in light of its original and inquisitive approach to exhibition-making. From the inaugural exhibition, a precedent was set: channelling the energy of Marcel Duchamp by way of eclectic presentations of artworks, design pieces and found objects that take inspiration from the father of Conceptual Art, not only nodding to his famed work The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1915–1923), more commonly known as ‘The Large Glass’, but through embracing experimental juxtapositions.

Playful use of concepts and materials are still to be found and the current “rolling” exhibition is in case in point. Staged in three parts, After Mallarmé is curated by Michael Newman, who is Professor of Art Writing at Goldsmiths, University of London. The heady thematic exhibition riffs off the works and legacy of French poet Stéphane Mallarmé to reflect on ideas of spaces, the page, the book, chance, mobility and contingency. Whereas, previously this year, Francesco Neri: Boncellino offered a more classic take via a selection of quiet and meditative, mostly black-and-white portraits of farmers and the farming community in the countryside around Modena in northern Italy, ‘a census of a village’s population’. Large Glass’ represented artists are: Hélène Binet, Guido Guidi, Hendl Helen Mirra, Francesco Neri and Mark Ruwedel.

Flowers Gallery

Flowers Gallery

21 Cork Street, London, W1S 3LZ

+44 020 7439 7766

82 Kingsland Road, London, E2 8DP

+44 020 7920 777

flowersgallery.com

Heavyweight Canadian photographer Ed Burtynsky may occupy much of the limelight at Flowers Gallery and their presence at art fairs such as Photo London and Paris Photo (Burtynsky was recently the subject of back-to-back exhibitions at the gallery’s Cork Street space which coincided with Saatchi Gallery’s major 2024 retrospective, BURTYNSKY: EXTRACTION / ABSTRACTION, the largest exhibition ever mounted in Burtynsky’s 40+ year career), but it boasts an impressive roster of photographers. This has been built up over years, first by Diana Poole then Chris Littlewood who established the department now run by Lieve Beumer. Among them: Edmund Clark, Boomoon, Shen Wei, Robert Polidori, Julie Cockburn, Gaby Laurent, Tom Lovelace, Simon Roberts, Esther Teichmann, Lorenzo Vitturi, Michael Wolf, Mona Kuhn, Nadav Kander and Lisa Jahovic, all recognised for their engagement with important socio-cultural, political and environmental themes. Aficionados of the medium may hope for further in-depth and major photography exhibitions in due course from the esteemed gallery, but despite Flowers’ deep commitment to photography, it works across a range of media within contemporary art.

Flowers has presented more than 900 exhibitions across global locations, including from New York and Hong Kong outposts, and lists a total of 80 represented artists. Established in 1970 by Angela Flowers (1932–2023), Flowers has long held East End venues, initially in the heart of Hackney with Flowers East on Richmond Road, set up in 1988, before moving to Kingsland Road in Shoreditch in 2002, a 12,000 square foot venue spread over three floors of a 19th century warehouse, arguably London’s most elegant white cube space within which to view photography. ♦

—

Tim Clark is a writer and curator based in London. He is Editor in Chief at 1000 Words, Artistic Director at Fotografia Europea in Reggio Emilia, Italy, and teaches at The Institute of Photography, Falmouth University.

Thomas King is Editorial Intern at 1000 Words and a student on BA (Hons) Culture, Criticism, Curation at Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London.

Images:

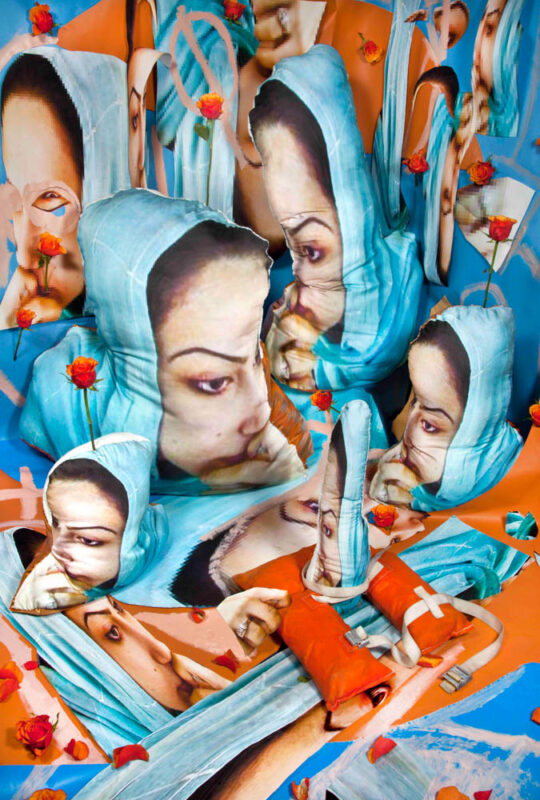

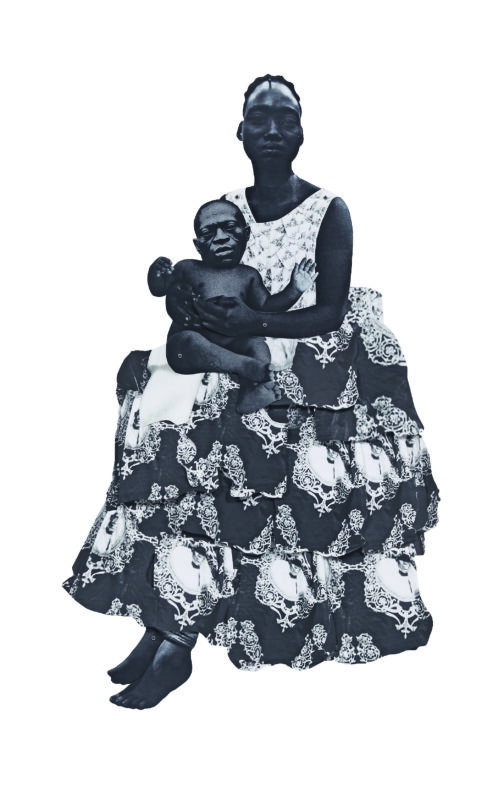

1-Autograph, London. © Kate Elliot

2-Hélène Amouzou: Voyages exhibition at Autograph. 22 September 2023-20 January 2024. Curated by Bindi Vora. © Kate Elliot

3-Wilfred Ukpong: Niger-Delta / Future-Cosmos exhibition at Autograph. 16 February-1 June 2024. Curated by Mark Sealy. © Kate Elliot

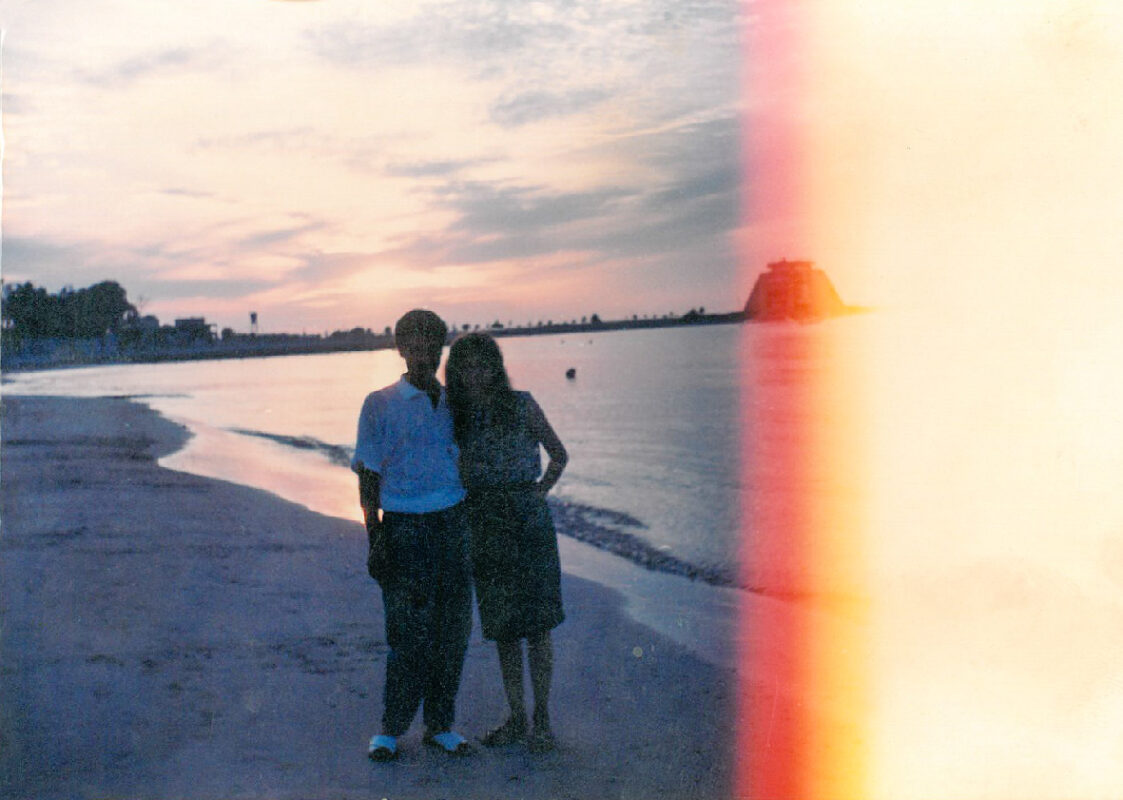

4-Gibson Thornley Architects, V&A Photography Centre. Installation view of Untitled (Giant Phoenix), 2022, Noemié Goudal, Photography Now – Gallery 96 © Thomas Adank

5-Gibson Thornley Architects, V&A Photography Centre – Photography and the Book – Gallery 98 © Thomas Adank

6-Gibson Thornley Architects, V&A Photography Centre – Photography Now – Gallery 97 © Thomas Adank

7-The Photographers’ Gallery, London. © Luke Hayes

8>9-Daido Moriyama: A Retrospective exhibition at The Photographers’ Gallery. 6 October 2023-11 February 2024. © Kate Elliot

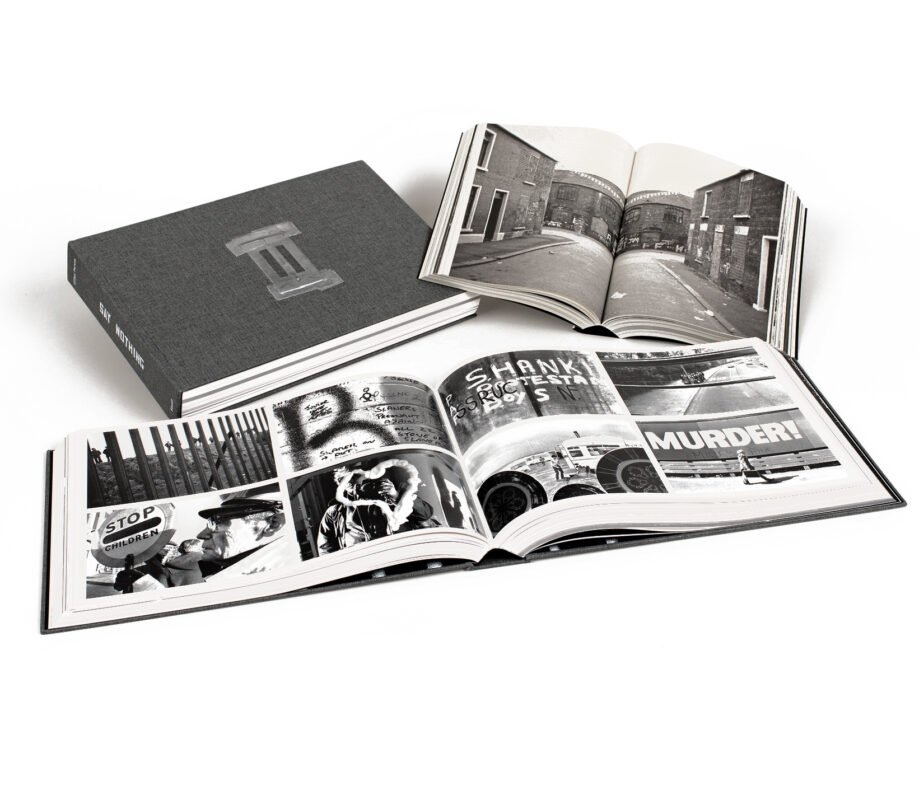

10-Ursula Schulz-Dornburg: Memoryscapes exhibition at Large Glass Gallery. 13 May-1 July 2023. © Stephen White and Co

11-Francesco Neri: Boncellino exhibition at Large Glass Gallery. 19 January–16 March 2024. © Stephen White and Co

12-Guido Guidi: Di sguincio exhibition at Large Glass Gallery. 3 February-11 March 2023. © Stephen White and Co

13-Flowers Gallery, Cork Street. © Antonio Parente

14-Edward Burtynsky, New Works exhibition at Flowers Gallery, Cork Street. 28 February-6 April 2024. © Antonio Parente

1000 Words favourites

• Renée Mussai on exhibitions as sites of dialogue, critique, and activism.

• Roxana Marcoci navigates curatorial practice in the digital age.

• Tanvi Mishra reviews Felipe Romero Beltrán’s Dialect.

• Discover London’s top five photography galleries.

• Tim Clark in conversation with Hayward Gallery’s Ralph Rugoff on Hiroshi Sugimoto.

• Academic rigour and essayistic freedom as told by Taous R. Dahmani.